1. Introduction: Rationale for Selection

The MyHealth case study points to how e-government health initiatives, even if it may only be an information service, can be gender-responsive to women’s primary health care, and privacy and confidentiality needs. While the approach stems from an equal access to health care rationale, seemingly neutral in centering the individual as the key actor in her/his own health and well-being, it has helped make professional health-care information more accessible to women, and thereby encouraging them to be better informed about their health care issues.

1.1 Background

The MyHealth portal was created to better enable primary health care. Primary health care refers to essential health care that is based on scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology, which make health care universally accessible to individuals and families in a community. Primary health care includes all areas that play a role in health, such as access to health services, environment, and lifestyle. Its approach is proactive using preventive measures, managing chronic disease, and encouraging self-care recommendations. Primary health care also includes services to decrease delay and increase timely access to the health care system, offering better health outcomes. Primary health care is often characterised by a team approach which allows individuals to get the right care by the right provider; the facilitation and sharing of information by health care providers; a focus on promoting health, preventing illness, and managing chronic conditions; a connection to the individual’s community; and enabling the individual to play an important part in her/his own health and well-being.

The MyHealth portal provides health education materials to the public. It is an online service provided by the Ministry of Health Malaysia under the Telehealth flagship application of the Multimedia Super Corridor (see Figure 1). As of February 9, 2016, there were over eight million visitors to the portal.

Figure 1:

MyHealth Portal

Source: www.myhealth.gov.my, 2016

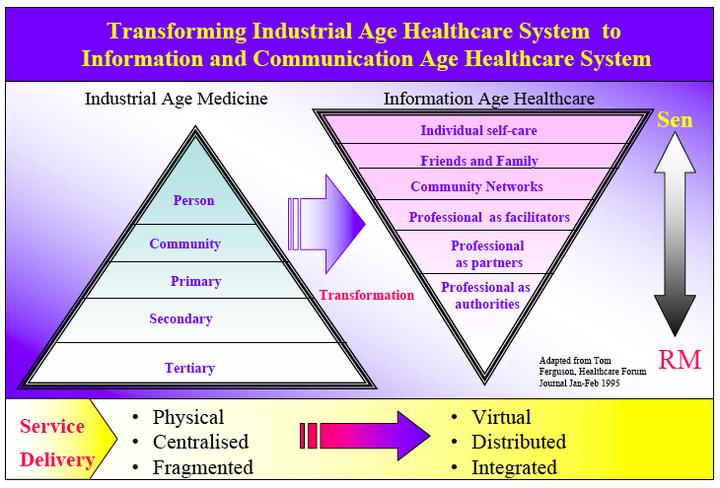

As part of Malaysia’s Telehealth flagship application, MyHealth is expected to change the health care system in Malaysia to become a more integrated, extensive and virtual system with the aim of providing fair, accessible, and high quality health care services. By providing detailed information on health issues as well as a list of health clinics, hospitals and so on, users are expected to be better able to understand their health issues, and detect health risk symptoms at an earlier stage. Online services are also available for health risk assessments, and visitors can view the client’s charter, and give feedback on the portal. It is therefore expected that the MyHealth portal will help achieve the Ministry of Health’s vision of health care services, as outlined in Malaysia’s Telemedicine Blueprint of 1997,1 which emphasises focus on wellness where individuals, families, and communities play an important role in health care (see figure 2).

Figure 2:

Transforming Malaysia’s Health care System

Source: Hisan 2006.

This vision is further underpinned by the four goals of the health care system as follows:

- Wellness focus: Provide services that promote individual wellness throughout life

- Person focus: Focus services on the person and ensure services are available when and where required

- Informed person: Provide accurate and timely information and promote knowledge to enable a person to make informed health decisions

- Self-help: Empower and enable individuals and families to manage health through knowledge and skills transfer (Hisan 2006).

As can be viewed from Figure 2, the emphasis is on empowering the individual to be fully aware of her/his health care needs by providing her/him with the correct information and knowledge so that she/he can make informed decisions with the concerned health care personnel (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016). The development of the MyHealth portal is therefore guided by Malaysia’s health policy vision of a nation of healthy individuals, families and communities, that is expected to be achieved through a health care system that is equitable, affordable, efficient, technologically appropriate, environmentally adaptable and consumer friendly, while emphasizing quality, innovation, health promotion, respect for human dignity, and community participation towards an enhanced quality of life (Hisan 2006).

The homepage of the MyHealth portal highlights health notices and warnings, current health issues, and information on health networks for children and adolescents, adults (which includes a health network for women)2 and senior citizens. It further provides two menus. The left-side menu links visitors to information and knowledge that caters to the health care needs of toddlers and children, adolescents, adults, and senior citizens.

The menu also provides specialised information and knowledge on food consumption, medication, and dental and mental health. Information and knowledge is provided through various channels, such as Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/myhealthkkm with 37,075 likes), Twitter (https://mobile.twitter.com/MyHEALTHKKM, with 1,446 followers), Instagram (https://instagram.com/myhealthkkm, with 664 followers), and YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/user/MyHEALTHKKM, with 2,531 views of main introductory video of MyHealth and 127 videos on various health-related topics).3 The right side menu provides visitors shortcuts to web pages for a quick search to topics by alphabetical order: the directory of both government and private hospitals, government clinics (village clinics, dental clinics, health clinics, community polyclinics, thalassemia test health clinics, mother and child health clinics,and 1Malaysia clinics), national health department, state health department, the health district offices, and health care centres by non-governmental organisations in each state; the frequently asked questions section; events and activities; quizzes; useful links; publications; and health campaigns.

The portal also has a site map, which can further aid visitors in finding the information they need. Visitors can choose to subscribe to the MyHealth mailing list by providing their e-mail address and first name only. While generally the overall website navigation system and information is in the national Malay language, some key pieces of information are available only in English. This may prove problematic even though Malaysia enjoys a high adult literacy rate of 94.1 per cent in 2012, with a 98.4 per cent literacy rate for males in the age group of 15 to 24 years old, and 98.5 per cent literacy rate for females in the same age group in 2015 (UNICEF 2016; see also UNESCO 2015).4 The ability to speak, read, and write in English among Malaysians has reportedly declined as a result of the pass percentage in the English language national examination (SPM) conducted for 17-year olds, being reduced to a standard of 6 out of 100 (Khoo 2015).5

The portal is regularly updated.6 The number of transactions on the MyHealth portal indicates that the use of the portal by the public has increased over time. There was, however, a small drop in usage in 2015 (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Types and Number of Transactions on MyHealth

| Type of Transactions | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MyHealth Portal |

728,376 |

1,263,710 |

1,943,644 |

1,868,917 |

|

MyHealth Health Risk Assessments |

13,888 |

10,383 |

11,009 |

5,914 |

|

My Health Ask the Expert Service [a response is guaranteed in not more than 14 work days] |

2,361 |

1,118 |

1,915 |

1,084 |

Source: http://www.myhealth.gov.my/?p=1607, 2016

2. Insights on Creating an e-Government Institutional Ecosystem that Promotes Gender Equality

2.1 Normative Shifts

2.1.1 Greater Accessibility of Health Care Information

The MyHealth portal is one of the ways of addressing the rising costs of health care. By providing a virtual online system as a reliable alternative to accessing accurate and updated health care information and knowledge across all possible health care issues, women need not worry about costs of travelling to a health clinic or specialist clinics, and paying consultation fees for what might be basic health care information or knowledge already accessible online. Information is also accessible in written, visual, and verbal forms. The information which is provided and updated by medical professionals becomes more accessible to women. Often, health professionals spare little time to explain things to their patients, particularly if there are gender barriers, such as the perception that the woman will not be able to understand the information, or the preference to speak to the man in the household/family.

2.1.2 Ensuring Affordability of Health Care

About 90 per cent of the Ministry of Health’s budget goes towards providing secondary and tertiary care, while only ten per cent of that goes to servicing primary health care—the first level of contact that individuals, families and communities have with the health care system. Within the Ministry of Health, the use of IT is regarded as part of the support system and infrastructure of the health care system. As such, costs are not passed over to patients. Health care fees are regulated and only charged for services and treatment. The Fees Act governs how much the public health sector facilities can charge patients. As such, the costs of health care services are subsidised by the Malaysian government by about 95 to 97 per cent (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016). These subsidies are borne indirectly from the Ministry of Health’s annual budget.

Primary health care has slowly been emerging as a health priority for the state, as explained by Amirudin Hisan, (Director, Teleheath Division, Ministry of Health):

“Even though from the very beginning, Malaysia already had a very good focus of providing public health care to the population, the fact was that, even in the 1990s, something like about 70 per cent of the total budget of MOH was going towards secondary and tertiary care. Only about ten per cent of that was going to primary care, and the rest of that was going to the public health services. So, we were trying to slowly move that proportion towards primary care, [in] getting more resources, and one of the ways in which the Director General at the time [approached this] was [in thinking how] we can incorporate IT into the delivery of health care, and if IT itself [could promote] primary [health] care and support secondary and tertiary [health] care, that would be a way of facilitating that change or transformation. We are still in that process. If you were to look at our Malaysia plan, our five year Malaysia plan for development, if you look at the health component, every year we ask to move towards that, but it’s still a very long process mainly because the demand for secondary and tertiary care, there’s still a lot of unmet demand and that we still have to fulfill, and because secondary and tertiary care almost always cost more than primary care, even though our range of services in primary care is getting [wider], but still the amount of budget allocation towards primary care is very slowly shifting, increasing, not [to the extent of] what we were thinking about but very slowly” (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016).

2.2 Shifts in Rules/Enforcement

2.2.1 Emphasis on Integrated Health Systems that are People-Centred

The development of the MyHealth portal and its role in serving and empowering the individual with health care information and knowledge that is correct demonstrates how important it is to have a Telemedicine Blueprint that is forward-looking. Malaysia’s Telemedicine Blueprint was developed in 1997. Even after two reviews, the Blueprint remains valid for Malaysia’s health care system (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016).

“We keep on saying that [health care] should be person empowered, it should be connected health [interoperability of systems and networked], it should be promoting wellness, it should be equitable, . . . [I]n some ways, before having IT in place, we were already working in that direction, now with the systems we’re trying to put in place, we’re trying to make sure that those systems will be moving us more and more in that direction. Back in the 1980s and in the early 1990s, when we started developing systems, a lot of our IT systems were vertical systems, how we managed the information, they were vertical silos. Nowadays, it’s not. There is information flowing between systems. I think we were one of the first countries in Southeast Asia to actually develop a national health data dictionary, that means if you’re developing a health IT system, and your system is going to collect this information that’s been defined under the national health data dictionary, then you should follow the definition of that data in your systems, this will then ensure that when you want to share the information, everything is standardised and easily integrated.” (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016).

2.2.2 Securing Privacy and Confidentiality

Because the MyHealth portal does not capture personal data other than gender and that which is disclosed by the user in their health care questions, it ensures user autonomy and by extension, protects their privacy and confidentiality. Women and girls are able to independently do their own research and ask questions without worrying about potential stigma and discrimination especially when it comes to issues relating to sexual and reproductive health and rights. Information is available on reproductive health as well as on health during pregnancy.

Additionally, the Ministry of Health not only complies with Malaysia’s Security Policy for ICT, but also puts into place additional measures (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016). For example, any information on personal data of a patient is only accessible from within the system or facilities where the system is located.7 External access such as through smartphones have to be directly registered with the server. Access is further curtailed by the user access control policy, which determines who can have access to what, when, why, and how (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016).

2.3 Shifts in Practices

2.3.1 Interoperability

The MyHealth portal can be viewed both through proprietary and open source platforms (Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, and Safari). Access of MyHealth is further facilitated through mobile devices such as the iPhone, iPad, Android, Blackberry, smartphone, PDA, Symbian, and other similar devices that are able to read XHTML 1.0 code and Wireless Application Protocol (WAP).

4. Impacts on Women's Empowerment

By prioritising its focus on the health care needs of the individual person, the MyHealth portal recognises that gender inequality is a result of the unequal power structure that can operate within a family, where decision-making tends to lie with the one who wields the most power (Amiruddin Hisan, interview, 2016). By enabling many forms and channels of access to health care information and knowledge, the MyHealth Portal is accessible to women and girls who may otherwise have had little access.

An analysis of the MyHealth portal through the Gender at Work framework reveals that it has mainly impacted institutional/systemic issues in relation to women's empowerment.

Table 2:

Analysis of the Empowerment Outcomes of the MyHealth Portal Using the Gender at Work Framework

| Informal | Formal | |

|---|---|---|

|

Individual |

NA |

Access to and control over public and private resources

|

|

Systemic |

Socio-cultural norms, beliefs and practices

|

Laws, policies, resource allocations

|

Questions from women and girls are not further filtered, suggesting a departure from judgmental and moral policing attitudes. The forward-looking Telemedicine Blueprint of 1997 for the country is one enabling factor. The Blueprint seeks to empower the individual, irrespective of gender, with information and knowledge that is correct and accurate so that informed decisions on health care can be made with the concerned health care personnel. The emphasis on anonymity and protection of personal data and information provides women and girls the assurance of privacy and confidentiality when accessing the MyHealth portal.

The MyHealth portal also addresses issues of access to, and control over, public and private resources in the formal sector. MyHealth provides accurate information and knowledge to the public for their use. Because it is a reliable source of information and services are provided free-of-charge to users, these factors can encourage better health-seeking behavior and practices of the individual that prioritises primary health care. This in turn better enables affordability of health care information and services (e.g. Ask the Expert) for women and girls.

4.1 MyHealth’s Potential

MyHealth has potential in ensuring a wider holistic approach to individual health care needs. Content on the MyHealth portal contains health-related information on sensitive issues such as rape (including gang-rape), violence against women, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). This is indeed commendable but the information needs to be placed more upfront rather than hidden under other headings like “adult” or “adolescent”. More comprehensive legal advice in relation to health care issues could be provided, such as what women can do within the law and to whom they can go to for further advice (including credible NGOs who have a proven track record on these issues), or at least, useful (and reliable) links to such information. Because women and girls can be subjected to patriarchal norms of the family and health care providers, legal advice pertaining to health care issues that is more accessible and provided in ways that allow anonymity would help women and girls tremendously. This includes legal advice pertaining to women’s rights to make decisions over their own bodies and to cover controversial issues such as the right to abortion (including in situations of rape), or in relation to procedures such as tubal ligation.

5. Recommendations

More than half of the queries directed to MyHealth’s Ask the Expert Service reportedly came from females.8 However, as the numbers in Table 1 indicate, not many people avail of this service and the number of transactions has been reducing. Further efforts to strengthen the outreach the portal could enhance access to, and use of the portal, such as through community health workers or extension workers, specifically by women and girls, as well as mediating the use of the portal in rural areas. The low number of online transactions may also indicate that 14 work days is too long for users of Ask the Expert service. The waiting time could be better managed, possibly by categorizing queries based on keywords, and shortening the wait time between three to five days.

Changes in gender perspectives and expected behavior are also necessary. Health information related to sexuality should be based on up-to-date information in the medical and psychological fields. Information on issues such as “sexual promiscuity” could benefit men and boys as well as women and girls and encourage men and boys, women and girls to practice safe and consensual sex.

References and Sources of Information

1997. Malaysia’s Telemedicine Blueprint: Leading health care into the information age. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health.

Amiruddin Hisan, Dr., Director, Telehealth Division, interview, 19 January 2016.

Hisan, Amiruddin, Dr. 2006. “Malaysia’s health: Transforming health care services through ICT”. Presentation at the Inaugural Meeting of the Global Alliance for ICT and Development, 19–20 June. Accessed 20 December 2015. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/gaid/unpan033231.pdf.

2016. “Malaysia: Statistics”. Accessed 9 February 2016. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/malaysia_statistics.html.

2015. “Malaysia: Education for all 2015 national review”. Accessed 9 February 2016. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002297/229719E.pdf.

Khoo, Jean. 2015. “A secondary school teacher reveals the ugly truth about Malaysian education on Facebook”. Vulcan Post, 19 November. Accessed on 3 July 2016. https://vulcanpost.com/453971/secondary-school-teacher-shares-fb-ugly-truth-malaysian-education/

- Malaysia's Telemedicine Blueprint of 1997 was an initiative by the Malaysian government to employ the use of telehealth in the country health care system. The integration with Integrated Health Enterprise (IHE) in 2007 reorganised the telehealth structure into 5 major components namely Lifetime Health Record (LHR) & Services, Lifetime Health Plan (LHP), Health Online, Teleconsultation (TC), and Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

- The link unfortunately is not working as at 9 February 2016. On further investigation, links to other networks like the ones for children and adult men were also not working. This might have to do with the upgrading of the portal.

- Data on followers and views are as at 9 February 2016.

- Literacy rates have generally risen between the Malaysian Population and Housing Census of 2000 and 2010. In 2010, for example, for the population aged 10 and above the literacy rate increased from 91 per cent in 2000 to 95.2 per cent. The literacy rate for the three states of Kelantan, Sarawak and Sabah that had the lowest rates in the 2000 census reached 92.1 (85.8), 89.3 (81.6), and 93.4 (84.6) per cent, respectively. The literacy rates have also increased in the rural areas of the three states having the lowest literacy rate in 2000; the state of Sarawak which had the lowest rate in 2000 improved from 72.1 per cent to 82.1 per cent in 2010.

- See https://vulcanpost.com/453971/secondary-school-teacher-shares-fb-ugly-truth-malaysian-education/.

- A visit to the portal on February 9,2016, showed that the portal had been last updated on January 13, 2016.

- Users of the MyHealth portal may register themselves to fully utilise the features of the portal. Information that is required includes name (first and last names), e-mail address, username, and choice of password. Other information requested but which is not made a requirement are telephone number, birth date, gender, height and weight.

- Amiruddin Hisan, Dr., Director, Telehealth Division, interview, 19 January 2016.