E-Government for Gender Equality

This research studied the e-government institutional ecosystem in order to understand better how norms, rules and practices relating to e-government can contribute to women’s empowerment and gender equality. Starting with the premise that any scrutiny of e-government can be meaningful only if it is held up against the test of good governance and citizen accountability, the study looked at how women’s citizenship rights are being impacted by e-government. Focusing on five country contexts, and 12 case studies, it tried to explore how e-government addresses women’s exclusion from governance, recognizing their equal claims as citizens. It also mapped the many different ways by which e-government, when designed gender-responsively, contributes to shifts in gender orders.

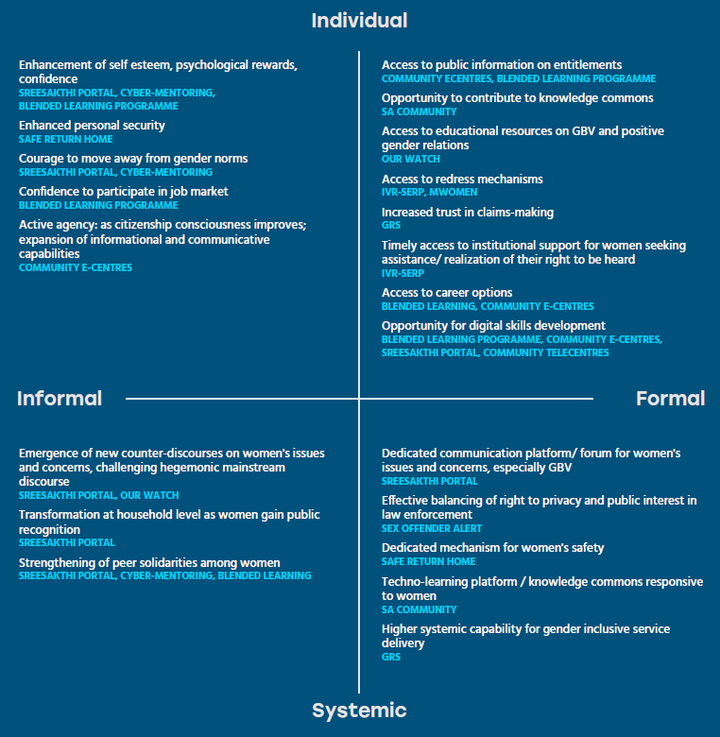

This chapter discusses the key insights from the case studies on the potential of e-government to lead to transformative outcomes along the four quadrants of the Domains of Change framework (the highlights of this discussion are summarized in Figure 2) It also presents a detailed analysis of the findings regarding the norms, rules and practices found to be significant to engender e-government.

6.1 What the Case Studies Reveal About Empowerment Pathways

The 12 case studies of ‘good practices’ in service delivery, citizen uptake and connectivity that were undertaken across the 5 contexts reveal that e-government has the potential to create positive outcomes for women’s empowerment, at the individual and institutional level, and in formal and informal realms. The Domains of Change framework has been used to reflect the key empowerment outcomes emerging from the case studies (see Figure 2). For a case-specific analysis of empowerment outcomes, see Annex II.

Figure 2

Empowerment outcomes of ‘good practices’

Shifts in Quadrant 1: Individual-Formal

E-government initiatives can open up access to new information and knowledge resources for women, strengthen their claims-making vis-a-vis public institutions, and bring easier access to redress mechanisms.

SA Community has brought new opportunities for women to participate as producers of, and contributors to, the digital information and knowledge commons. The Blended Learning Programme provides women participants access to new digital skill sets. As one woman participant in the programme reflected during the field research for the case study, “The Blended Learning Programme contributed to widening our knowledge and sharpening our skills.” By providing facilitated public access and through digital literacy trainings, the Community Telecentres and Community eCentres have boosted ICT skill levels of women beneficiaries.

The championing of GRS by Parent Leaders from the local community has contributed to trust-building among women beneficiaries, who are gradually beginning to use the online grievance redress mechanism. The timely and coordinated response from state agencies to GBV reports that IVR-SERP ensures access to redress for women fighting GBV.

The Blended Learning Programme has enhanced women’s awareness about the existence of online government services and their entitlements. Similarly, mWomen has the potential to educate women about their legal rights, in the context of domestic violence.

Shifts in Quadrant 2: Systemic-Formal

E-government initiatives can strategically leverage the digital opportunity for making governance accountable and responsive to women’s needs and interests.

As evidenced from the experiences of Our Watch and the Sreesakthi Portal, the ICT opportunity for creating a dedicated communication platform for women’s issues and concerns, such as GBV, can enable inclusion of women’s perspectives in public-political discussions.

Making the techno-design architecture of e-services gender-responsive can bring a number of gains for women’s empowerment, as supported by insights from the GRS, Safe Return Home, and Sex Offender Alert initiatives. The GRS has adopted the practice of using the metadata about grievances to correct design flaws in compliance monitoring, payment releases and household targeting systems of the programme. This has helped in refining the programmatic design to make it more responsive to beneficiaries, the majority of whom are women. Safe Return Home has effectively used the open GIS database developed by government to create a personalized safety app for women, which enables them to inform their friends and family members about their whereabouts. Sex Offender Alert has focused on balancing public interest in issuing notifications about convicted sex offenders with the right to privacy of the offender by instituting a number of legal and technical safeguards that restrict republication and recirculation in media of information accessed through this system.

Shift in Quadrant 3: Systemic-Informal

E-government initiatives that harness peer networking and communication possibilities can bring women’s voices into the public sphere and help them gain peer support and solidarity. Such initiatives can also lead to status gains for women at the household level.

Our Watch challenges the prevailing culture of silence on GBV, as does the Sreesakthi Portal. As one woman user of the Sreesakthi Portal reflected:

“Earlier women were alone in the confines of their homes and had nowhere to turn to, when faced with violence and harassment. The portal provides them a space in addition to their immediate neighbourhood group where they can come out in the open about these problems, and seek help. Women no longer need to be quiet. The portal makes individual experiences of violence public and connects women to many other women who are their peers. This helps in reducing abuse in the home.”

Another area where shifts can be discerned is in the strengthening of peer solidarities. For example, through the Blended Learning Programme, women have been able to expand their networks of peer support. In fact, a group of female students have put together a social media group to support each other in their training. The Cyber-mentoring Initiative has facilitated the emergence of strong mentoring relations between women in the early stages of their career and senior women professionals. Similarly, the Sreesakthi Portal is instrumental in the trans-local solidarities forged by members of women’s collectives of the Kudumbashree programme, across different districts.

Shifts in Quadrant 4: Individual-Informal

E-government initiatives can build women’s self-esteem and confidence, help them acquire the critical discernment that is necessary for challenging gender norms, and further their active citizenship agency, through an expansion of informational and communicative capabilities.

Sreesakthi Portal, Cyber-mentoring Initiative, and Blended Learning Programme have provided a number of psychological rewards for women participants. The Sreesakthi Portal has enhanced women’s self-esteem through its training programmes for digital literacy and creation of a space for women’s self-expression. In the case of Cyber-mentoring, the support received by women mentees has helped them step out of prescribed gender roles and even pursue offbeat careers. As one mentee recollected:

“At the start of this year, I was distressed that my dream was to become a soap drama playwright. I was alone as most of my university friends were pursuing careers as office workers or thinking about studying at a graduate school, while those who studied drama with me were from a different age group. My mentor, (herself a senior playwright), helped me to ask myself why I wanted to be a playwright and what I really wanted. She gave me a lot of advice. I realized what was really bothering me, and the answer came out very easily.” 126

The Blended Learning Programme has reaffirmed women’s self-confidence to participate in the labour market.

E-government interventions can equip women to challenge prevailing gender norms, as the case of Our Watch illustrates. The social media outreach strategies of Our Watch seem to have been especially successful in this area. The Line campaign has led to a shift in attitudes towards VAW among participants, as more and more youth exposed to the campaign have started calling out instances of behaviour that crosses the line (i.e., behaviour that may be abusive or disrespectful).127

Finally, as the case studies on blended learning and Community eCentres demonstrate, digital skills training programmes directed at women expand their informational and communicative capabilities, making it possible for them to reap economic and social gains.

6.2 Ingredients of a Gender-Responsive Ecosystem

What are the ingredients of e-government that lead to empowering outcomes for women? This central objective of the study is addressed in the following discussion. The section lays out key findings from the case studies about service delivery, connectivity and citizen uptake, the three elements of the e-government ecosystem, synthesizing the critical parameters that seem to matter in e-government design for gender equality.

Service delivery

Ingredient 1: Balance between digital processes and human mediation

A fine balance between standardization of digital processes and agility of human mediation is critical for building women’s trust in e-government services, but institutional cultures of governance also matter in trust perception.

The rapid diffusion of mobile phones has spurred many developing country governments to design m-government initiatives on scale. However, literacy and affordability barriers prevent economically disadvantaged women from taking advantage of these endeavours. Smart phone access also tends to be lower for women. Even as new cultures of interface with government are evolving, the role of human mediation is still recognized as important for service efficacy, as community level programmes show.128 SMS push services (like mWomen in Fiji, which sends SMS based information nuggets) need complementary services to ‘close the loop’, when women victims call in and require direct services. Even in developed countries, e-government programming for women explicitly needs to synergize its online approaches with offline services. Our Watch does not provide counseling or emergency services to those at risk of, or who have experienced, domestic violence. However, all social media sites of the programme are continuously monitored and moderated by experts, and anyone at immediate or potential risk is directed to the national emergency phone number and also advised to contact the 1800 RESPECT counselling service. This information is displayed prominently in all Our Watch publications.

Encouraging women to get online and enabling them to transact with public institutions virtually is an important step to building their confidence as active citizens. In the case of first generation users, human intermediation can facilitate this process and break down the distance between individual women and their public service entitlement. Facilitation to become familiar with e-government and acquire the technical skills to navigate websites and seek public information is the basic step where the role of ‘facilitated access’ cannot be overemphasized. E-jaalakam, in India uses college students as facilitators who train neighborhood groups to start using e-government services.129 However, eliminating or minimizing human processes in online services potentially offers citizens the advantage of predictability and better levels of efficiency through standardization. The IVR-SERP case shows how a gender-responsive e-government system is programmed through a strategy where routinized technology systems and a personalized response system come together. IVR-SERP enables problem resolution through a rule book; but it also has a simple tracking method that can escalate difficult cases to higher levels of authority, when personalized problem solving is needed. Our Watch recognizes that gender equality is not about techno-deterministic ‘plugs’ to ‘fix’ problems, but “the ability to collaborate, foster partnerships and engage communities”, even as it uses multiple technology platforms not only for information processing, but also discourse shaping. Their website testifies to this approach: “We will genuinely engage organizations and communities to ‘co-produce’ solutions as people, communities and networks hold the tacit knowledge needed to come up with the best solutions for their situation”.130 Further, technological choices and methods are reviewed continuously for optimizing user experience on different technology interfaces even with low speed connections.

In the GRS case of the Philippine Conditional Cash Transfer programme, complaints resolution and appeals work through a data system that captures, resolves, and analyzes grievances from beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries about the programme. Grievance resolution strategies are clearly defined in the operations manual and the estimated maximum timelines for complaint resolution are established. The programme has also rolled out numerous trainings for grievances officers, staff who are designated as city/municipal links, and parent leaders who are community level outreach staff, to address queries and problems at all levels. Selected non-government agencies are formally engaged to monitor the programme and the same feedback mechanism is available to them. There are regular monthly reviews of grievance status. The procedures of how complaints are filed and reported are published online and offline. These are shared to all partners and beneficiaries. Periodic metadata analysis has helped address concerns by alerting programmatic administrators to the magnitude of particular concerns and by improving compliance monitoring, payment releases, and household targeting systems. A high degree of agility characterizes the interplay between technological and human processes.

However, affordability, accessibility and connectivity barriers as well as prevailing attitudes that consider grievance-reporting to be a futile exercise create a trust deficit in the grievance redress system of the Philippine Conditional Cash Transfer programme. Even though the possibility of anonymous reporting has contributed to some increase in grievance reporting, existing problem-solving structures may be perceived as too removed and therefore less credible.

Also, what Mission Convergence, a single window service delivery system meant for women in New Delhi, India, shows is that tamper-proof beneficiary tracking is no guarantee of inclusion.131 Guarantees for being heard by higher authorities, as in the IVR-SERP case, can foster trust. Citizens’ trust in the predictability of e-services may also require collective representation mechanisms that can transmit the shared concerns of women from marginalized social groups.

Ingredient 2: Boundary spanning in service delivery and robust governance of new partnerships

Boundary spanning in e-government initiatives brings the much needed flexibility in taking public services to women citizens, but it also requires strong and transparent governance measures to ensure that new service delivery arrangements do not undermine women’s interests.

Boundary spanning refers to the blurring of organizational boundaries of governance institutions, due to the shift away from traditional, hierarchical structures to collaborative modes of functioning that stress cross-sectoral partnerships between governmental agencies, private sector and civil society to address knowledge and expertise gaps in the human resource pool of the government.132

The OECD points to how this shift in recent times to horizontal or non-hierarchical forms of governance with boundaries that blur across organizations and sectors, nationally and globally, presents fundamental public governance challenges.133

The research indicates the many different ways by which service delivery spans boundaries:

- Interdepartmental convergence. Safe Return Home mobile app in the Republic of Korea was made possible thanks to the opening up of government GIS data and interministerial agreements.

For the Blended Learning Programme in the Philippines, e-TESDA has entered into agreements with the ICTO for the use of the Community eCentres and public library facilities for all, especially women, who may prefer to use safe spaces other than those at the TESDA Women’s Centre. It also seeks the support of local government units in information dissemination through social media. - Citizen involvement in design. SA Community facilitates informational convergence across a wide range of stakeholders who provide information, without impacting service delivery arrangements at the citizen end. Through partnerships with local organizations that contribute to the portal, it manages integration of information at the content level without integration of the technical architecture. Content is licensed under Creative Commons licensing which enables information reuse. Authorization and verification of information is largely dependent on interagency trust. The creative use of flexibilities enables maximization of information at minimal cost.

- Private sector partnerships. In the IVR reporting system for GBV of SERP India and the Cyber-mentoring Initiative of the Republic of Korea, private partners have been contracted for the management of the technical platform underpinning the service.

- New organizational forms. Our Watch is an independent, not-for-profit organization, set up by Australian governments (initially the Commonwealth and Victorian State Governments), and works closely with state, territory and federal governments, in the development and delivery of government-funded projects.

These trends in e-government also shift the structures of power and control, as new decision-makers outside of government now get involved in public policy processes. Some examples, emerging from this research, of how ‘boundary spanning’ arrangements have been creatively and effectively managed, are detailed in Box 1.

Box 1

Making boundary spanning work for gender-responsiveness

One key area in e-government innovation pertains to managing new stakeholder relationships that governments get into for technical and other expertise. From a gender equality stand point, these arrangements to span boundaries and maximize efficiency must also pay due attention to accountability and sustainability. The research has suggested a few pointers in this direction:

Overcoming the silo model of functioning: In South Australia, as noted in the case study, when SA Community and its partner organization sa.gov.au came together, resolving the negative consequences of the silo structure of government was the principal design requirement. Achieving this was not easy and called for working contra to the hierarchical structure of the bureaucracy through effective public sector stakeholder management, change management and governance arrangements to put the citizen at the centre.

While allowing for flexibility at the edges to ensure gender-responsiveness, these emerging governance practices in e-government have relied on responsibility- and role-sharing, with differing degrees of contractual formality.

Effective division of roles in interdepartmental convergence: In the case study of the Sex Offender Alert system in the Republic of Korea, work flow arrangements were modified for greater efficiency — with a division of roles between the Ministry of Justice that began dealing with all the registries on sexual offenders, and the Ministry of Gender Equality which took on the role of disclosing and notifying all information on the sexual offenders.

Prioritizing domain expertise rather than IT expertise, in contracts: In the Cyber-mentoring Initiative, Republic of Korea, the decision to hire a specialized women’s agency for managing the web portal for connecting mentors and mentees was taken when it was felt that a technical IT agency was not effective in handling the project on its own. Currently, a women’s agency with domain expertise is responsible for the initiative in its entirety, and this agency subcontracts a technical IT agency for maintenance of the portal.

Optimizing contracts with technology service providers: In the case of SERP, the organization in India that runs the IVR reporting system for GBV, there is a realization that integrating data across its programmes can support beneficiaries much more. As a result, SERP is now looking to rationalize its software applications and reduce the number of contracts with technology service providers. Mandating open technical standards is another consideration e-government initiatives seem to be using, in the interest of project sustainability. The IVR of SERP runs on an Asterisk open platform to work around vendor lock-ins.

Despite the many lessons and emerging tactics in managing new modalities of service delivery, bigger challenges do remain. In the age of boundary spanning, unconventional modes of citizen outreach become more and more common, such as through social media and SNS sites, as government becomes increasingly non-hierarchical in all aspects of its functioning. However, governments may or may not have a social media policy. In the Philippines, we see a laissez-faire approach to social media, with variations across departments and initiatives, while the Our Watch case in Australia shows the strategic deployment of social media. The question of fixing responsibility for protecting user data and privacy on social media platforms remains unanswered in both approaches. This is a critical gap, since there is ample evidence of intermediaries who are unresponsive to cyber attacks faced by women who may challenge prevailing gender norms on these platforms.

There are also significant risks for women’s privacy rights in the ‘big data’ age, where a lot of data are interlinked. Governments resort to extensive collection of personal data of citizens to create foolproof beneficiary authentication systems. The interlinking of data across different agencies, and sometimes between government-held and private data sets, also makes it difficult for citizens to have control over how their private information is put to use.

Public private partnerships involving corporate players, which comprise one key modality of boundary spanning, are strategically useful for public sector agencies to gain access to technical expertise that they traditionally lack, and overcome bureaucratic inflexibilities of legacy systems. At the same time, PPPs that are not managed well can present a number of challenges for women’s rights, as discussed below:

- Blurring of accountability in service delivery systems: Privatization of service delivery at the last mile or e-services management must have clear service level guarantees for the citizen. Accountability arrangements are therefore important from the standpoint of citizen rights. In the case of this research, this was found to be an issue of concern for Fiji, whose e-services are managed by Pacific Digital Technologies, a private company. In India, the privatization of one-stop-shop kiosks for last mile service delivery has created a situation whereby village entrepreneurs running these kiosks prefer higher income groups, paying less attention to the service needs of vulnerable groups.134

- Weakening of long-term sustainability: PPPs in this area could pose long-term sustainability challenges. The CeCs in Malvar entered into a partnership with Microsoft to obtain basic software applications for their digital literacy trainings, but this arrangement provided free access only for a limited period of time. As a result, in the long run, costs of digital literacy trainings went up. India’s experience under the National Digital Literacy Mission (NDLM) reveals another challenge. The NDLM selects private partners to implement digital literacy trainings, through a bidding process, and offers a piece-rate compensation135 for successful completion of the qualifying exam by training participants. Such a for-profit approach may lead to a prioritization of the instrumental objective of skills training over the wider goal of expanding citizenship capabilities, while transacting digital literacy.

- Private management of citizen data: Oftentimes, governments enter into private sector collaborations for the design and implementation of services underpinned by data backbones, without data governance guidelines. For example, in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, the Management Information System (MIS) of the state’s rural wage employment programme136 availed by the poorest women has been developed in collaboration with a private sector company, who continues to handle its maintenance. In the absence of data governance guidelines, there have been delays from the private partner in responding to data requests from government, and of inaccuracies in reporting, which is an impediment to timely payment of wages to the poor.137 Similarly, in Fiji, in the mWomen mobile-based informational service, all data is collected and managed by Vodafone Foundation, which is under no contractual obligation to share these details with the government. Such privatization of sensitive personal citizen data (individuals seeking assistance for GBV, in this case) potentially poses a risk of privacy violations.

Ingredient 3: Straddling investments in data and connectivity capacities

Investment in creating robust public data systems and women’s access to quality connectivity must go hand-in-hand to ensure the relevance and effectiveness of e-government innovations for women.

The role of government in taking the steps to close the loop between informatization-digitization and connectivity cannot be overemphasized. The basis of gender-responsive e-government is an agile information system with sex-disaggregated data (on development and social welfare indicators), data that can be put to gendered use (like spatial data about the city) and feedback data that can help improve e-services for women. This is borne out by the experience of the Republic of Korea — whose early efforts at informatization paid off in the design of the mobile app Safe Return Home. The spatial data set used by this initiative was a product of systematic collation and digitization of administrative geographic information undertaken in the 1990s, engaging various stakeholders, including the Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs, the Ministry of Land, Transportation and Maritime Affairs, and local governments. Near ubiquitous mobile connectivity in the Republic of Korea can ride upon the publicly owned spatial data repository, creating a data-connectivity opportunity for responding to women’s safety needs.

Conversely, it is the quality of connectivity and accessibility of the Internet that drives accelerated use of e-government services. For example, in the case of SA Community, Australia, information is continuously crowdsourced for the portal while its uptake is democratized through state libraries and local government agencies on high speed broadband. The instinctive value that communities engaged in ICT based local knowledge and information processes perceive for connectivity is illustrated in the simple finding that in the Philippines, between Community eCentres that have connectivity and those that don’t, users clearly prefer the former.

On the one hand, data readiness is vital to efficient services; on the other, service efficacy itself is a product of continuous and active use by women. Where connectivity is a challenge and project or government staff are recruited to relay women’s messages, such mediated connectivity can only be an interim solution. Therefore, what the research tells us is that long term gender-responsiveness hinges on the virtuous cycle of service provision, use, contextualization and citizen participation, that is a product of the seamless twinning of quality connectivity and data readiness.

Ingredient 4: Gender-responsive data governance

The redefinition of governance through data regimes demands new gender-responsive legal, policy and implementation frameworks underpinning e-government.

As data becomes foundational to governance, good governance practice must adapt to new data-embedded processes. Data can be considered as not only a technical detail, but also a sociological artefact. It is therefore important that principles of privacy and anonymity are at the centre of debates on governance. Personal data in e-government databases can endanger women’s privacy rights, especially since control over data by state and non-state actors who may have access to such data brings disproportionate power. Unless well managed, technical systems can centralize authority, transgressing individual rights and undercutting local control over problem solving. In the case of vulnerable women, considerations of privacy are magnified. Data protection legislation is therefore vital. Beneficiary rights in the Philippines are protected by a privacy law. The TESDA Women’s Centre, in the Philippines, strategically invoked the law for gender mainstreaming to formulate its institutional data security policy and processes, thereby ensuring that the rights of women in their Blended Learning Programme are not compromised.

The possibilities to manage data in disaggregated and geographically bounded ways through localization expand the scope of good governance significantly. The Sex Offender Alert system in the Republic of Korea shows how the right to privacy (of the offender) and information personalization/localization (for access by registered individuals and schools) work in tandem. The IVR-SERP initiative in India is able to track GBV in a disaggregated manner thanks to the Management Information System. The efforts of the Grievance Redress Scheme in this regard show how offline systems must work in tandem with online ones, especially to connect women who may not have the means to communicate with regimes of data governance that are distant and remote.

Some governments are also adopting open source and open standards policies for interoperability of platforms and data for greater efficiency or integrated or convergent service delivery, as SA Community in Australia demonstrates. The FOSS Act in the Philippines for instance mandates the use of open source and open standards.

Also, open data is emerging as an important measure of transparency and accountability. Safe Return Home builds on the integrated national geographic information system, a repository of public spatial data, indicating the role of robust data sets in the public domain to meet the demands of e-government innovation.

What is clear is that legal provisions and administrative protocols for data governance are vital for good governance that promote women’s empowerment and rights. As discussed in Box 2, the principles of data governance are still evolving.

Box 2

Data related challenges in e-government: some gender perspectives

The age of data poses various challenges to women’s citizenship and rights.

Existing national statistical systems do not adequately capture sex-disaggregated data needed for effective design and implementation of e-government. Data on women’s use of the internet, online services, m-services, level of ICT skills, nature and extent of VAW online, are not available, and if they are, they are based on small-scale surveys. A dedicated mechanism for data collection and situation analysis is absent.

As state agencies and their private partners collect massive amounts of data, the interlinking of data sets and resultant loss of privacy makes women in particular much more vulnerable. This is exacerbated by the lack of appropriate legislative frameworks to govern data regimes in a way that effectively balances concerns of privacy and transparency.

Citizen uptake

Ingredient 1: Technology design that aims to expand women’s choices and engagement in government structures

Achieving women’s uptake of e-government is about triggering a sense of entitlement that can expand their choices as citizens. The values underlying governance guide the techno-design, either ‘gendering’ such a sense or reinforcing the role of technologies in furthering structures of gender inequality.

The real indicator of e-government maturity for women’s empowerment is not just the readiness of government to deliver. It is about how much or to what degree e-government services are able to bring a sense of entitlement to women citizens. This depends on the values guiding the techno-design aspects. For example, the Community eCentres from the Philippines have opened up new empowerment pathways for women users, as their design is guided by a wider capabilities approach to provisioning access and implementing digital literacy programmes for citizens. Similarly, Our Watch in Australia encourages women and youth to debate, question and challenge prevailing gender norms. The design of the Sreesakthi Portal in India underscores the value of an ’online public’ for women. When government officials or community and political leaders participate and respond to women in such online public platforms, e-government processes reinforce women’s ‘right to be heard’. Allowing for the anonymous reporting of grievance, as in the GRS case from the Philippines, is another example of a measure to encourage women to use the service, bringing a minimum service level guarantee in claims-making.

Design elements in policies, rules and implementation could also prevent women from accessing information and the public services to which they are entitled. For example, telecentres could require proof of identity/residential address and signatures. Such bureaucratic requirements can pose barriers to those who have low literacy, are homeless/transient or otherwise marginalized because of lack of formal identification. Similarly, moderation of women’s online participation could promote paternalism, in the name of protecting women from bullying or trolling. To illustrate, discussion forums in the Sreesakthi Portal of the Government of Kerala are moderated for online posts. Similarly, system operators in the Cyber-mentoring Initiative in the Republic of Korea have the authority to monitor and review the mentoring processes. Such moderation may be a double-edged sword, undermining women’s rights through censorship or protectionism.

The endeavour to design in a way that the technical responds to the social and does not exacerbate inequality and discrimination is therefore a key test for e-government maturity. Technological design is a set of choices. It can compromise rights or unleash citizenship.

Open data, without protocols for data protection can lead to the publication of data that endangers citizen privacy. The challenges associated with this are illustrated by the case of IVR-SERP in India. In this initiative, data about survivors and perpetrators of Gender Based Violence, recorded on the IVR system, are published online. Open data, especially on women’s rights violations is important. It is a means to reflect the extent of a problem that is heavily underreported. At the same time, the granularity of the data is of key concern, and so, decisions to publish information about individual women must also reckon with the need to respect and protect their confidentiality and safety. The Sex Offender Alert initiative of the Republic of Korea illustrates one possible solution to address the question of effectively balancing privacy and ‘transparency in public interest’ requirements through effective techno-design. This initiative uses both technical sophistication (such as identity authentication for data access and software that restricts the creation of local copies of information at the user end) and legal checks (legal restrictions on republication of information accessed through this service) in an effective manner, to balance the public interest requirement of issuing alerts about known Sex Offenders and their case histories, with the requirement of maintaining survivor confidentiality.

Reliance on proprietary software could compromise longer term considerations of cost and sustainability. For example, in the case of the Community eCentres in the Philippines, the proprietary products used in the digital literacy trainings need to be purchased after the expiry of the trial period. This has cost implications for sustained provision of the services. Hardware and software lock-ins may be attractive and even useful for short term impacts, but as the SA Community initiative shows, public technology choices in terms of technical (vesting the ownership of the platform with a not-for-profit organization SA Connected; and mandating the use of a Creative Commons license) and techno-social (democratically managed information system processes and governance structures) aspects resonate strongly as accessibility enablers for women.

Ingredient 2: Frontline workers to nurture women’s appreciation for, and trust in, digitalized service delivery

Effective access to e-government services for marginalized women needs contextually relevant human facilitation at the last mile, often provided by a new cadre of extension workers.

Human intermediation plays a vital role in effective e-government service delivery for women, especially in developing country contexts. Not only because women may need technical support to navigate virtual spaces, but also to make e-government familiar and build trust. The cases reviewed point to a cutting edge role played by frontline intermediaries, including knowledge workers in Community eCentres of the Philippines, librarians in South Australia, and members of the local Community Development Societies in the case of Sreesakthi Portal, India, who have all been reported by users as teachers, guides and stewards. These frontline workers have been instrumental not only in ensuring that women’s personal transactions are dealt with, but in nurturing local appreciation for technological mediation of service delivery. A generic digital divide approach is now well recognized to have limitations. Disincentives and barriers to access are well documented and include women’s inability to pay for access to services, constraints on mobility and multiple burdens. Frontline intermediaries often go to where women are to enlist them for e-services. The GRS of the Conditional Cash Transfers programme in the Philippines uses a community orientation model that includes the participation of parent leaders at the last mile, in their operational design that includes the city/municipal links, the Conditional Cash Transfers programme’s officials at the municipal or regional level and independent NGO monitoring teams. Parent Leaders who are mostly women act as a conduit for information between beneficiaries and management of the Conditional Cash Transfers programme. They play an important role in capturing grievances and facilitating grievance redress in the community.

Ingredient 3: Leadership of national women’s machineries to encourage gender-responsive e-government

Women’s uptake of online services calls for system-wide appreciation and commitment to the gender transformative opportunity of e-government. The leadership of women’s machineries is vital in accelerating progress.

Gender mainstreaming and gender budgeting frameworks and laws for women have been referred to in high impact initiatives like Our Watch, Australia; the Blended Learning Programme of the vocational training authority, TESDA, in the Philippines; and cutting edge participatory governance models like Sreesakthi Portal in India that engages marginalized women across Kerala state in policy dialogues. These cases reflect a strong ownership of lead agencies, such as in education or rural development, which have appropriated the e-government opportunity. These initiatives also demonstrate a shared pan-organizational vision and willingness for boundary-crossing in design for effective impact, as well as the important role of local champions, femocrats and enterprising individuals in government.

However, the systemic assimilation of the gendered opportunity that e-government presents requires an agency that can drive the vision, guide the implementation and monitor the outcomes, across all sectors and levels of government. The experience of the Republic of Korea for instance shows how the women’s machinery plays a key role in aligning the national effort for informatization with women’s policies to use ICTs more actively for women’s empowerment (see Box 3). The mobile app in the Sex Offender Alert system was born out of an interministerial task force in which the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family worked with the Ministry of Justice on the issue of violence and safety.

Women’s machineries in all countries have unfortunately not risen to the challenge and opportunity for a gender-responsive e-government. They may also not be empowered with the necessary resources, technical, financial and human, to coordinate and inform e-government implementation. It is clear however that the next phase of e-government for women’s empowerment will need much more than occasional entrepreneurs from the system; ownership is key and there should be a central role for the national women’s machinery.

Box 3

government-initiated efforts to address the gender digital divide in the Republic of Korea

Before the establishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family138 in 2001 as the national women’s machinery in the Republic of Korea, it was the Ministry of Information and Communication that mainly led informatization programmes for women. The Framework Act on Informatization Promotion and the Act on Eliminating the Digital Divide (1995) provided an impetus for this. 139 Subsequently, the Ministry of Gender Equality established the Basic Plan for Promoting Women’s Informatization (2002–2006), setting out a rather ambitious policy vision on women’s capacity to participate in the information society, and going one step forward from previous approaches on the gender digital divide that defined women’s role more passively.140

Every five years, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family establishes a Basic Plan on Women’s Policy through which national policy directions for women’s empowerment and gender equality are broadly defined. The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family’s policy directions on women’s informatization are also in line with the Basic Plan on Women’s Policy. The approach here shows the lead that the national women’s machinery provides in bringing about the much needed alignment between digital inclusion of women and national policy directions for gender mainstreaming and women’s empowerment. It also indicates the role the Ministry plays in being proactive about a rapidly evolving scenario, so that women can stand to gain from emerging opportunities for active citizenship.

Connectivity

Ingredient 1: Models to promote meaningful online participation for women

Connectivity policy is not just a technical consideration for e-government. It is equally about promoting meaningful cultures of online participation through which women can experience active citizenship.

Broadband infrastructure, according to the Broadband Commission for Digital Development set up by the ITU and UNESCO, is critical for social inclusion in the digital age.141 However, mere availability of connectivity cannot bring about gender inclusion in e-government service delivery. This is especially true for countries where broadband adoption is new. Assumptions about connectivity matter most. In the SA Community initiative of Australia, the commitment to reach low speed users and hence a minimalist design of the website for easy and quick information access reflects premises that address social exclusion.

If being connected can enhance learning about the civic-public aspects of citizenship, it is more likely to be perceived as valuable, especially by first generation Internet users becoming familiar with e-government. Giving women access to a space for mentoring and being mentored (Cyber-mentoring Initiative, Republic of Korea); a safe space for self-paced and supported learning (Blended Learning Programme, Philippines); and a channel to voice their perspectives in the public domain (Sreesakthi Portal, India), the deployment of connectivity opens up various avenues for active citizenship. Where being online means an assertion of agency, women see connectivity as empowering. In the case of the Sreesakthi Portal in India, socially and economically marginalized women use an online portal for discussions about gender issues. Their training in the use of the platform is directed at their participation in public discussions. When connectivity cannot reap social returns, or expand existing networks and bring value, many women, particularly from rural and aboriginal backgrounds, are most likely to reject it.

Countries are exploiting new ways to reach women citizens through mobile-based services. Our Watch’s focus on young people through the Line campaign capitalizes on mobile connectivity diffusion, using out-of-the-box thinking to define gender-based violence as a public issue requiring social debate on norms. Even where mobile access is still an issue, programmes are harnessing community volunteerism to respond to women’s needs, as the IVR in SERP does by involving local women leaders who relay messages.

Poor infrastructure is a roadblock to effective roll-out of e-government. Coupled with lack of human capacity and appropriate legislation, the absence of a strong connectivity backbone142 has impacted e-government maturity in the Pacific. In India, state policy on connectivity infrastructure and broadband continues to see connectivity as divorced from the key issue of meaningful cultures of use at the last mile. However, there is realization that connectivity cannot be reduced to a technical issue. As a key informant from the Department of Telecommunications, Government of India contacted for the India component of the research observed:

“While imagining a broadband infrastructure, it is important for us to go beyond a unitary imagination of the broadband at the last mile as an undifferentiated pipe — and think about the different types of services that will run on it — in specific, capacities to handle data-rich services need to be assessed and adequately planned for. Also, it may not be correct to assume that the last-mile broadband retail will be automatically taken care of, by market forces, once the basic infrastructural network up to the Panchayat level (rural local government) is provided by National Optic Fibre Network. As at this point, in rural areas, demand for broadband may not be large enough to attract private players, and so, other creative models for last mile retail involving women’s collectives, Gram Panchayats (local governments), local cable operators, need to also be examined. Finally, there needs to be investment in developing relevant content services for the rural population using the digital opportunity, in addition to providing for the infrastructure.”

Pilot projects like Sanchar Shakti, in India, have used the Gender Budget of the Universal Service Obligation Fund, to bundle connectivity with informational services for rural women. While gender based policies to bring women online and become citizen-users of e-government are an urgent policy imperative, approaches in this regard have to go beyond creating a client base for e-government.

The push for connectivity and informatization in the early 2000s in the Republic of Korea resulted in a plan to train 5 million people to build their capacities in information production and move beyond information consumption. The Second Step Training Plan on Informatization of Citizens 2003 aimed at equipping 3.5 million ‘e-Koreans’ to use information technologies at work and in their everyday lives, providing basic trainings for computer and Internet skills for 1.5 million people from vulnerable groups, through the Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity and Promotion.

Quality connectivity can propel new generation users to become e-citizens using a range of public services online. However, sociocultural barriers to access may also leave behind most women and older populations, unless connectivity goes with e-government literacy. While digital inclusion policies do recognize the role of digital literacy programmes, the success of such interventions is contingent upon how socially excluded populations perceive digital skills training as a means to join the mainstream. Rather than top-down modalities, bottom-up strategies are more likely to be effective in encouraging marginalized women to embrace emerging technologies (see Box 4).

The involvement of various arms of government is also a prerequisite. The Philippine Digital Literacy for Women Campaign is a programme that offers free digital literacy training to women nationwide. Launched in 2011, it engages multiple stakeholders, including the ICT Office, Telecenter.Org, the University of the Philippines, the Philippine Community eCentre Network, Intel Philippines, telecommunication companies and other non-government organizations. The programme aims to cover 10,000 women and give them the skills for informational access, networking, and exploring socioeconomic opportunities to improve their lives.143 Also, the Bureau of Alternative Learning System in the Philippine Department of Education uses its Community eCentres for basic computer education or digital literacy courses. Davao City, for instance, offers basic computer literacy courses to youth as well as to women from the ten tribes living in the city. 144

Box 4

bottom-up initiatives for women’s digital literacy: The case of e-jaalakam, Kerala, India

E-jaalakam (literally, e-window) is a path-breaking digital literacy initiative that has been developed by the Department of Economics, St. Teresa’s College in Ernakulam district of Kerala state, in India, in partnership with the Kerala State IT Mission. The initiative, launched in 2012, focuses on using women undergraduate students of the college as Master Trainers to conduct digital literacy trainings for women and girls in neighbouring communities, through a cascade model. The Kerala State IT Mission has supported the college in the development of the training material and in developing the curriculum for the training of the Master Trainers. What makes this initiative stand out is its recognition of digital literacy as a pathway that enables women to attain full digital citizenship. As Nirmala Padmanabhan, the Head of the Department of Economics and the architect of this initiative shared in a key informant interview conducted for this research, “The focus of e-jaalakam is to ensure that women and girls know enough about computers and the Internet to access information about various schemes and services, and are familiar with all the government websites. Part of the task is also to change the way women think of their relationship with government. In one of our early trainings, one girl asked me ‘Why should I care about all these schemes and services? Someone else at home will take care of it anyway’. I told her, ‘It is precisely to counter such a perception about governance being a male preserve that girls should get into e-government transactions’.” In 2014, this initiative won the Chief Ministers’ Award for Innovation in Service Delivery in Kerala state.

Ingredient 2: Subsidized access and safe public spaces for including all women

Subsidized public access is important for gender-responsive e-government, especially as Internet and smart phone use among women is still low in many developing countries. In and of itself, public access seems to hold value for women’s networking, peer support and social capital.

Women-friendly e-government services need affordable and ubiquitous connectivity so that all citizens can be included. Creative service delivery ideas that target women will have to consider strong, locally viable solutions to make sure that connectivity reaches women. One important factor in this is the sustainable financing of such initiatives, in order to provide affordable and financially viable options. In some cases, public access has been provided free-of-charge, such as the Sreesakthi Portal, which uses free public access infrastructure points provided at the village level, through the Department of Rural Development. These spaces assist women in accessing e-government services. Without full subsidy or universal access, e-government may not be able to make inroads, especially where the benefits of digital communication and transaction are not yet apparent to women. The lack of affordable and accessible broadband for poor households is one of the reasons for the slow uptake of online channels for grievance filing in the Grievance Redress Scheme.

Government outreach services in local communities can help engage women when they provide opportunities that expand life choices and are perceived as a welcoming space. Commercial Internet access points can be intimidating for women.145 Women beneficiaries of e-TESDA, Philippines prefer the Women’s Centre to cybercafés that they find unwelcoming. e-TESDA’s women beneficiaries see the Centre as a highly enabling space for technical assistance, and affirming for the collective learning and peer support received. The Community eCentres of Malvar, Philippines, are another good example of a gender-responsive public access facility.

In addition, public access points provide other benefits. The role of libraries in fostering ICT and information access, especially for women, has been well documented.146 The public library network in Australia, for instance, has been vital in the SA Community initiative that functions as a public information repository used extensively by local social service organizations. In South Australia, libraries have taken on the primary role (outside the formal education system) in digital literacy training and provide technical support especially to older women citizens. In the Philippines, Community eCentres have emerged as public access spaces that provide users a range of digital possibilities, ICT skills training, online courses for alternative education, and e-government services.

- Minister of Gender Equality and Family. (2013). Cyber-mentoring Report: Sisterhood Diaries.

- Based on research conducted by Our Watch and the Department of Social Services, Government of Australia.

- See Rajalekshmi, K.G. (2014). Multipurpose nature of telecentres: the case of e-governance service delivery in Akshaya telecentres project (Doctoral dissertation). The London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved from http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/935/1/Kiran_Multipupose-nature-of-telecentres.pdf, 21 April 2016. NGO experiments such as the info-ladies initiative in Bangladesh also recognize the critical role of last-mile intermediation to make service delivery effective for marginalized groups. See Bouissou, J. (2013, July 30). ‘Info ladies’ go biking to bring remote Bangladeshi villages online. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/jul/30/bangladesh-bikes-skype-info-ladies, 21 April 2016.

- Kerala State IT Mission, Government of Kerala. (n.d.). e-Jaalakam. Retrieved from http://www.itmission.kerala.gov.in/e-jaalakam.php, 21 April 2016.

- Our Watch, op.cit., www.ourwatch.org.au.

- Menon-Sen, K. (2015). Aadhar: Wrong number or Big Brother calling. Socio-legal Review, 11(2), pp. 85-108. Retrieved from http://www.sociolegalreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Aadhaar-Wrong-Number-or-Big-Brother-Calling.pdf, 21 April 2016.

- Edwards, Halligan, Horrigan & Nicoli, op.cit.

- Edwards, Halligan, Horrigan & Nicoli, op.cit.

- Kuriyan & Ray, op.cit.

- National Digital Literacy Mission, Government of India. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions (FAQ). Retrieved from http://ndlm.in/frequently-asked-questions-faq.html, 21 April 2016.

- This MIS serves as the data backbone that contains information about worker attendance and wage payment status across all villages of the state, where the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme is operational. This programme has contributed enormously to rural women’s economic empowerment.

- Based on field research conducted for the study in India.

- On inception, the Ministry was named Ministry of Gender Equality. Its name was changed to Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, subsequently.

- Jung (2001), cited in Lee, S. et al. (2013). Women’s Use and Production of Information in the Age of Media Convergence, pp. 39-40. Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- Lee, S. et al. (2013), op.cit.

- Broadband Commission for Digital Development. (2015). The state of broadband 2015: Broadband as a foundation for sustainable development. Retrieved from http://www.broadbandcommission.org/documents/reports/bb-annualreport2015.pdf, 21 April 2016.

- Sovaleni, S. (2010). New roadmap for Pacific: The framework for action on ICT for development in the Pacific. Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/7-Mr-Siaosi-Sovaleni-SPC.pdf, 21 April 2016.

- Philippine Commission on Women. (2012). Local government initiative for women: Tanauan local government brings computer literacy at women’s doorsteps. In Convergence for women’s economic empowerment (p. 7). Retrieved from http://www.pcw.gov.ph/sites/default/files/documents/resources/GWP_magazine_2012_August_issue.pdf, 21 April 2016.

- Davao City. (n.d.). Programme summary of the alternative learning system. Retrieved from http://www.davaocity.gov.ph/davao/unesco/ict.pdf, 21 April 2016.

- Sey et.al., op.cit.

- Beyond access. (2012). Empowering women and girls through ICT at libraries. Retrieved from http://beyondaccess.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Beyond-Access_GirlsandICT-Issue-Brief.pdf, 21 April 2016.