2.1.1. Overview

A key goal of e-service delivery is to expand access to public information, welfare benefits and economic resources for citizens. Online services can also provide timely and effective crisis response to women and build their trust in governance systems. But this transformative potential towards women’s social and economic empowerment can be realised only when e-government policies promote gender-responsive design and implementation of public services. This is well-recognised in global policy debates on gender and development, such as the Beijing plus-10 review process, the UN General Assembly’s Resolution 66/130 on Women and Political Participation (UN GA 2012)1 and the ITU’s 2016 Action Plan to Close the Gender Digital Gap (ITU 2016)2.

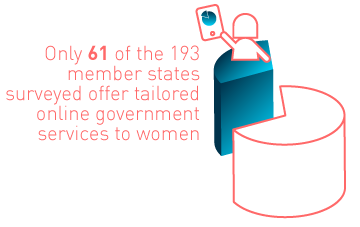

However, e-service delivery tends to be viewed as a ‘gender-neutral’ exercise in most contexts. The UN E-government survey (2016) found that only 61 of the 193 member states surveyed offer tailored online government services to women.

Also, only about one-third of the countries surveyed offer online services focused on poor, persons with disabilities and older persons (UN E-government Survey 2016)3.

The majority of governments fail to collect sex-disaggregated data on use of e-services, despite its critical importance in assessing progress towards Agenda 2030.

What this implies is that governments may tend to assume an undifferentiated user group in their design and implementation of e-services, thereby failing to account for the specific needs and priorities of women and segments of the population who face particular social, cultural and historical disadvantages in accessing government services as well as technology. The intersecting structures of social stratification (gender, class, race etc) that contribute to women’s exclusion from the benefits of full citizenship have, thus, largely remained unaddressed in the transition to digitalisation of services.

The design of local governance has been significantly influenced by the specific advantages that digital technologies bring for reach and timeliness of services and for participatory governance. The notion of “proximity government”, for example, seeks to reap the advantages of ICTs for a more open design. Bringing women’s needs and interests to the centre of such re-design of services can help overcome traditional barriers to their active involvement in local governance as well as sustained satisfaction as users of public services.

Incorporating a gender lens in e-service delivery systems calls for the following:

2.1.2. designing e-services targeted at women to address their specific needs and priorities.

2.1.3. bringing a gender perspective to the roll-out of all e-services.

2.1.2. Designing e-services specifically targeted at women

Women’s requirements with respect to welfare benefits and other public services vary by life stage, and socio-structural and geographic location. An adolescent girl needs a different basket of services when compared to a single mother struggling to run her household; an undernourished woman coping with a high risk pregnancy; a woman entrepreneur looking for support to enter new markets; or, an older, destitute woman trying to find affordable health care. Similarly, urban-poor women may have service needs that are different from their counterparts in rural areas.

Designing women-directed e-services, thus, includes the following two aspects:

- Building an integrated basket of public services for women, organised along a ‘life cycle’ approach.

- Creating an e-service delivery system that is geared towards promoting rights-and empowerment agenda.

1. Building an integrated/convergent basket of public services for women

This section discusses the design elements that go into promoting a convergent service delivery experience for women users – addressing user-facing and government-facing aspects.

‘User-facing’ aspects refer to the front-end dimensions of e-service delivery design that determine user experience of e-services, such as design of e-service delivery interfaces. ‘Government-facing’ aspects pertain to the design of back-end architectures – the digitalised information and data systems that form the backbone of e-service delivery systems.

1.a. User-facing aspects

One-stop-shop portals for women-directed services: One-stop-shop portals facilitate the aggregation of public information and services from a wide range of departments and agencies into a single web space (UNDESA 2016)4. Currently, out of the 193 countries covered by the UN E-government Survey, over 90 countries have set up one-stop-shop portals. But there are only very few instances of such one-stop-shop portals being customised by country governments for women-directed e-service delivery, and some examples are discussed below.

Box 1. Customising one-stop-shop portals for women-directed services: Some government-led efforts

In Australia, where one-stop-shop portals have been set up by national and state governments to help citizens meet their service needs and priorities at different life-stages, the introduction of advanced search features has contributed to a customised service delivery experience for women users (McConchie 2016)5.

In the case of the Republic of Korea, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family has set up an exclusive one-stop-shop portal for women-directed services – titled Women’s Net – whose key features include:

- menu bars that categorise services according to key target groups – working women, mothers, women taking a break from their careers, women immigrants who are part of multicultural families, mothers etc.

- services to address women’s needs and priorities at different life stages.

- linkages to various social networking platforms and allied smart phone apps for m-service delivery.

- integration with the country’s national one-stop-shop portal that contains all government-to-citizen services (Kim 2016)6.

In Kutch district of Gujarat state, India, a local CSO – Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan – has developed a one-stop-shop portal, in partnership with district level government agencies, to support the work of one-stop-shop kiosks for convergent public service delivery to marginalised women from tribal communities, engaged in artisanal and dairy occupations. The portal is intended to serve as a resource for information workers/ infomediaries who process information and service delivery requests at the last mile. As these workers may themselves have low levels of textual literacy and digital literacy, the interface uses icons and visual graphics to aid ease of navigation. Information about different services has been organised using a ‘target group’ logic that is user-facing rather than a ‘departmental’ logic that is government- or system-facing. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Landing page of the one-stop-shop portal (Panjo Haq) developed by the Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan

Stand-alone web portals for specialised services: In Europe, the region with the highest number of countries offering targeted e-services to women (23), national governments have opted to set up a range of smaller portals offering specialised services rather than a single one-stop-shop portal. As early as 2010, EU member states such as Germany and Austria had set up independent portals to promote awareness on gender equality, and provide information about women-directed services (UNDESA 2010)7.

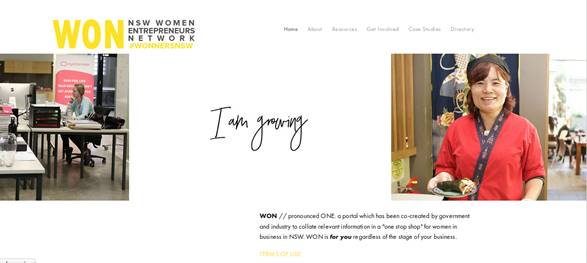

Australia, too, is witness to this trend of departments/ agencies launching their own smaller portals/ “portlets” (UN ) for specialised services – of which WONNSW.com.au, an initiative of the Department of Industry, New South Wales, is especially noteworthy. This portal seeks to be a single point of information about resources and support available from government and industry for women entrepreneurs in the New South Wales region. The WONNSW platform (Figure 2) contains a suite of resources such as “business plan templates, business viability assessment tools, an event calendar, creative design resources, grant and funding avenues, marketing and website options, networking opportunities” (NSW Department of Industry 2016)8.

Figure 2. http://www.wonnsw.com.au/

1.b. Government-facing aspects

Strategic design of information systems in public administration systems: Digitalised information systems can enable effective inter-deparmental coordination for convergent public service delivery, as demonstrated by Brazil’s Mae Coruja programme.

Box 2. Information systems for convergent public service delivery: The case of Mae Coruja

Mae Coruja (literally, ‘Mother Owl’) was launched by the state government of Pernambuco, Brazil in 2007, to provide a comprehensive set of health, education and social development services for pregnant women, new mothers, and children in the age group of 0-5 years. The programme has focused on integrated delivery of services – basic social protection, improvement of nutrition and food security, income generation, and early childhood care – in every municipality of the state. Implementation requires coordination in service provisioning amongst different departments such as Health, Education, Social Development, Women, Children and Youth, Planning etc. To achieve effective convergence, the programme has relied upon a periodic needs assessment amongst its intended beneficiaries to determine municipality-specific priority areas and targets; and tracking progress towards this through a web-based management information system – SIS Mae Coruja. This information system tracks women beneficiaries’ uptake of services from amongst different agencies in real time, which has contributed to strengthening service delivery integration/ convergence across different agencies.

Data analysis to assess user preferences: Appropriately combining traditional surveys with online opinion polls can enable effective tracking of user preferences, for responsive design. Women’s participation in such exercises is essential for governance that promotes institutional transparency and inclusive public decision making, as also acknowledged by Targets 16.6 and 16.7 of Agenda 2030. The Seoul single women initiative, launched in 2014, aims at providing a comprehensive set of support services for single women – covering housing, health care, neighbourhood safety, and employment. To ensure that the design of services reflects the priorities of the beneficiaries, the initiative has opened an e-policy forum inviting single women to voice their needs and priorities. Ongoing data analysis from this forum as well as periodic small-sample needs assessment studies on the ground shape the directions of this initiative.

2. Designing e-services with a view to promote women’s rights and empowerment

E-service delivery can promote positive outcomes for women’s empowerment, when it is based on a rights-based approach. This would include creating a policy and implementation framework that recognises women’s needs and interests, ensuring that service delivery expands women’s access to new information & knowledge resources, economic and social opportunities and crisis support mechanisms. Invariably, a positive shift in one domain of women’s lives is bound to lead to gains in other domains, as empowerment is not a linear process. More details of this are discussed in Module 1 and Module 5. Here, we provide examples of women-directed services that have succeeded in meeting their intended outcomes.

2.a. Initiatives that seek to expand women’s access to information and knowledge resources

In recent years, there have been a number of multi-sector collaborations in mobile based service delivery in the global South. Government departments, mobile telephone operators, private sector entities and CSOs engaged in content development have come together to harness mobile-based informational networking to expand women’s access to information about reproductive health, child care, nutrition, financial literacy and more (GSMA 2015, DIMAGI 2016)9. The GSMA mWomen programme is one such well-known example. It seeks to support the incubation of sustainable business models that provide mobile-based value added informational services directed at women, in emerging telecom markets, and persuade governments to use their Universal Service Funds to invest in the development of such services.

In recent years, there have been a number of multi-sector collaborations in mobile based service delivery in the global South. Government departments, mobile telephone operators, private sector entities and CSOs engaged in content development have come together to harness mobile-based informational networking to expand women’s access to information about reproductive health, child care, nutrition, financial literacy and more (GSMA 2015, DIMAGI 2016)9. The GSMA mWomen programme is one such well-known example. It seeks to support the incubation of sustainable business models that provide mobile-based value added informational services directed at women, in emerging telecom markets, and persuade governments to use their Universal Service Funds to invest in the development of such services.

Research and evidence from the ground indicate that such m-information services are successful in enhancing women’s status, when supported by the following conditions:

-

Content is creative and context-appropriate.

Content is creative and context-appropriate.In Bangladesh, the Aponjon maternal and child health care mobile information service – that has emerged as a collaborative effort between the Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action, the Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the social enterprise Dnet – pays special attention to micro-local cultural aspects. This service delivers voice messages twice a week – and offers both text and voice options, taking into consideration the low levels of formal education of women in the target area. Content development tries to ensure that the messages are entertaining, and not prescriptive. Therefore, for the voice messages, a ‘mini skit’ format has been adopted, in which real-life scenarios involving a pregnant woman, her family members, and a doctor, are acted out. As prevailing gender cultural norms result in a situation where male family members gate-keep women’s access to and use of mobile phones, a companion information service has been launched that is targeted at their husbands – which reinforces the messages directed at women, and encourages the involvement of men in pregnancy, birth and child care related decision making (mHealth Compendium accessed 5 September 2017; http://www.aponjon.com.bd/ accessed 5 September 2017).

Another example is the Dab IYO Dahab initiative, a US-AID supported collaboration between the international non-profit research and development organisation Education Development Centre and the mobile operator Souktel. This initiative sought to provide financial literacy services to improve money management skills of young women in Puntland, south-central Somalia, between 2008 and 2011. Building on the region’s tradition of oral storytelling, this m-learning service created an IAI/ interactive audio instruction mechanism which enabled participants to dial into an audio library and listen to voice clips on topics of their choice (UNESCO 2015).

-

Services are affordable.

Services are affordable.The Sanchar Shakti programme of the Department of Telecommunications, government of India, is a useful example of subsidised mobile information services that deliver free-of-cost, value-added mobile info services (over SMS/ Short Message Service and IVR/ Interactive Voice Response networks) to marginalised women. More details in Module 4.

-

Services are backed by institutional support for longer term impact.

Services are backed by institutional support for longer term impact.Mobile information services directed at marginalised women cannot do much to open up new pathways to empowerment, unless backed by concrete institutional support. For example, studies of mobile price information networks for marginal women farmers reveals that these services can be transformational, only if backed by governmental support for sourcing capital, subsidies/discounts for acquiring farm inputs, storage and warehousing facilities, and linkages to producer cooperatives (Burrell 2015)10.

This has been effectively accomplished by the m-learning initiative of the Open University of Sri Lanka11 that seeks to build financial literacy of rural women farmers. This initiative makes available weekly audio lessons and tests to course participants over a mobile IVR/ Interactive Voice Response platform. Additionally, the initiative has focused on building linkages with banks for longer-term impacts on livelihoods. Through an arrangement with the Regional Development Bank, credit services have been provided to participants who succesfully completed the course. The Open University of Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka Telecom Mobitel have launched another convergent digital enskillment service for daughters of women farmers who participated in the financial literacy training (Wanasundera and Herath 2017)12.

-

Pilots are appropriately institutionalised within government.

Pilots are appropriately institutionalised within government.Involving private sector and civil society partners in developing innovative pilots of m-information services can certainly make women-directed e-service delivery more creative. However, for such pilots to have long-lasting impacts, they should be institutionalised. The experience of the mWomen service in Fiji provides some useful lessons in this regard. The mWomen e-service is a subscription-based SMS service that offers a daily set of free info-updates on the following themes: women’s and children’s legal rights, family law, and gender based violence. It was initiated in March 2013, as a partnership between the Department of Women, Government of Fiji and Vodafone. In November 2013, an additional SMS Counseller component — a free short code number that members of the public can text to, for obtaining legal advice and counselling — was launched. A partnership was established with the NGO ‘Empower Pacific’ to assist users of this service. However, none of these collaborative arrangements were backed by formal partnership agreements between the parties involved. This has resulted in a situation where the government’s involvement has tapered off over time, and Vodafone is now the primary driver. For citizens, this means that there is no way they can demand minimum levels of service quality. Also, the long-term sustainability of the service has been called into question, as it is highly unlikely that the government will pick up the service if Vodafone ceases its involvement. This can already be witnessed in the SMS Counselor component – where the lack of formal financial support for the NGO ‘Empower Pacific’ has hampered the quality and reach of support.

-

Women are supported to use e-information through digital literacy.

Women are supported to use e-information through digital literacy.Government-led efforts to promote women’s access to information and knowledge resources can be fully effective, only when backed by efforts to build women’s digital capabilities. For more details, see the discussion on digital literacy programmes for women in Module 3.

2.b. Initiatives that seek to promote women’s enterprise and access to economic opportunities

Two specific ways in which e-services can expand economic opportunities for women entrepreneurs are detailed below.

Two specific ways in which e-services can expand economic opportunities for women entrepreneurs are detailed below.

-

An exclusive online marketplace for women entrepreneurs can help women overcome their exclusion from mainstream markets.

An exclusive online marketplace for women entrepreneurs can help women overcome their exclusion from mainstream markets.For instance, the webportal http://www.ejoyeeta.com/ (literally, victorious), set up by the government of Bangladesh in 2013 using its Innovation Service Fund, has enabled more than 60,000 women producers and 5,000 micro-entrepreneurs to advertise and sell their products online. In March 2016, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, government of India, launched a similar initiative – Mahila e-Haat (literally, Women’s e-marketplace) – where women entrepreneurs and self help groups and non-governmental organisations working with women artisans/producer cooperatives, across the country, can market their products. The portal eliminates middlemen, by facilitating direct contact between the vendor and buyer. Unlike mainstream e-commerce platforms, Mahila e-Haat also provides a peer discussion forum, e-learning services, support services for entrepreneurs. The year end review of the portal by the Ministry of Women and Child Development reveals that “...Women entrepreneurs/self help groups/non-governmental organisations from 22 states are showcasing approximately 1800 products/services. Women entrepreneurs/ self help goups/ non-governmental orgaisations registered as vendors have transacted business [volume of] over 2 million INR, which is a substantial amount keeping in mind the micro nature of the individual businesses” (Press Information Bureau India 2016)13.

-

Promoting peer networking among women entrepreneurs.

Promoting peer networking among women entrepreneurs.WeGATE (https://www.wegate.eu/who-we-are, accessed 2017)14, a web portal supported by the European Commission, seeks to be a hub for online networking, exchange and cooperation among aspiring and current women entrepreneurs – to help them identify timely and appropriate access to finance, business contacts, training and learning opportunities, and other resources, in the contexts that they are located in. Such ICT-enabled networking solutions are extremely important for women entrepreneurs, as oftentimes, gender social norms and the double burden of managing paid work and household responsibilities prevent them from engaging with the world outside their immediate communities (ADB 2014)15.

This constraint is at least partially addressed through peer discussion forums and personalised advice that is made available at the click of a mouse.

For more information on the digital opportunity for building women’s enterprise, see Module 2 of the Women and ICT Frontier initiative of United Nations Asian and Pacific Training Centre for Information and Communication Technology for Development. Access these modules at http://e-learning.unapcict.org/wifiinfobank/data/Module_C2.pdf

2.c. Initiatives that seek to address gender based violence

Crisis support: Mobile-based safety applications/ emergency apps have received a lot of attention in policy and programming for GBV prevention and promotion of women’s personal security. Investment in such apps may be useful when it is part of a larger effort to build a techno-enabled institutional support mechanism for gender based violence. In 2015, the city of Seoul launched a Safe City project in response to the rising number of street sexual assault cases that were being reported. Through a careful pattern analysis of crime records of the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency and data available with four support centres for victims of sex crimes, the initiative developed an effective plan for neighbourhood patrolling, with community involvement. Additionally, a hotline for effective response to distress calls has been set up. As many as 656 convenience stores across the city have been designated as “Women’s Safety Patrol Houses”. A woman can enter any of these 24x7 stores, if she is in a situation of distress – and the clerk on duty will then activate a wireless alarm that will immediately notify the police control room. A smart phone app has been used to supplement the initiative – the “Seoul Smart App” – which provides the location of these safety patrol houses.

Crisis support: Mobile-based safety applications/ emergency apps have received a lot of attention in policy and programming for GBV prevention and promotion of women’s personal security. Investment in such apps may be useful when it is part of a larger effort to build a techno-enabled institutional support mechanism for gender based violence. In 2015, the city of Seoul launched a Safe City project in response to the rising number of street sexual assault cases that were being reported. Through a careful pattern analysis of crime records of the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency and data available with four support centres for victims of sex crimes, the initiative developed an effective plan for neighbourhood patrolling, with community involvement. Additionally, a hotline for effective response to distress calls has been set up. As many as 656 convenience stores across the city have been designated as “Women’s Safety Patrol Houses”. A woman can enter any of these 24x7 stores, if she is in a situation of distress – and the clerk on duty will then activate a wireless alarm that will immediately notify the police control room. A smart phone app has been used to supplement the initiative – the “Seoul Smart App” – which provides the location of these safety patrol houses.

Another point to keep in mind – especially for governments taking the route of private sector collaborations for safety app development – is the need to ensure well-defined policies of privacy and/or terms of use for informed consent. Without this, the risk of identity theft and extralegal surveillance increases for users – as effectively demonstrated by a recent review of popular mobile safety apps (Lakshane and Chinmayi 2017)16.

Do’s and dont’s for designing mobile-based crisis support solutions/ Safety apps

|

|

GBV prevention: It is well recognised that gender based violence has its roots in patriarchal norms that condone it by reinforcing women’s subordination. Therefore, any effort at GBV prevention can be successful only when it attempts to transform deep-seated cultural norms and attitudes in communities, breaking the prevailing culture of silence on the issue. Undoubtedly, this is a long drawn process of deep socio-cultural change, but the Our Watch initiative, Australia, stands out as a success (See Box 3)

Box 3. Our Watch, Australia

Our Watch is a not-for-profit organization set up by the Victorian state government and the Commonwealth Government of Australia in 2013 to facilitate a “sustained and constructive public conversation with the aim of improving the public’s awareness of violence against women in Australia, ...growing the primary prevention movement...and encouraging people to take action to prevent violence against women and their children.”

The initiative uses a combination of traditional and new social media outreach and community events, to create an alternative discourse on gender and sexuality, and break the silence on domestic violence, as discussed below:

Engaging with national media to build their capacities for sensitive reporting of gender based violence.

Engaging with national media to build their capacities for sensitive reporting of gender based violence. Ongoing digital campaigns on social media and social networks (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, and blogging) to target parents, teachers, family violence sector workers and media about the urgency of the issue. One of these campaigns – titled the Line – is exclusively focused on young people in the age group of 12 to 20 years, and its intent is to question and challenge attitudes and behaviours that justify and excuse violence against women.

Ongoing digital campaigns on social media and social networks (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, and blogging) to target parents, teachers, family violence sector workers and media about the urgency of the issue. One of these campaigns – titled the Line – is exclusively focused on young people in the age group of 12 to 20 years, and its intent is to question and challenge attitudes and behaviours that justify and excuse violence against women. Setting up a closed discussion group for women survivors of violence, to help them forge networks of support.

Setting up a closed discussion group for women survivors of violence, to help them forge networks of support. Instituting ‘Respectful Relationships’ education in the school curriculum, and networking with public hospitals to ensure that emergency response teams are sensitive to privacy and confidentiality concerns in GBV cases. In addition, the NGO Doncare has been supported in developing an education app, that explains the connection between certain types of behaviour and abusive relationships, through an interactive learning module.

Instituting ‘Respectful Relationships’ education in the school curriculum, and networking with public hospitals to ensure that emergency response teams are sensitive to privacy and confidentiality concerns in GBV cases. In addition, the NGO Doncare has been supported in developing an education app, that explains the connection between certain types of behaviour and abusive relationships, through an interactive learning module. Partnering with local organizations to develop tailored violence prevention programs for two cultural and linguistic minorities.

Partnering with local organizations to develop tailored violence prevention programs for two cultural and linguistic minorities.

Source: (UNESCAP 2016)17

2.1.3. Bringing a gender perspective to the roll-out of all e-services

Ensuring that a gender perspective is brought into the roll-out of all e-services is vital to ensure effective uptake by women. Some strategies that have been successful in this regard are detailed below:

1. One-stop-shop kiosks/ e-service delivery centres that are gender-inclusive

In many countries in the global South, setting up one-stop-shop kiosks/e-service delivery centres in rural and remote communities, and urban-poor neighbourhoods, is an important strategy for ensuring the effective uptake of e-services by vulnerable groups with limited access to Internet connectivity or lacking in digital literacy skills to navigate e-service web portals. However, it is important to recognise that such spaces cannot automatically ensure inclusion of marginalised women in service delivery systems. These spaces will remain male bastions unless some specific design elements are introduced to make them gender-inclusive, such as:

1.a. Locating the centre in a space that is perceived as ‘non-threatening’ by women.

The Mission Convergence initiative of the state government of Delhi that has set up a network of one-stop-shop kiosks in urban-poor neighbourhoods, in partnership with local NGOs, has paid careful attention to this dimension. These kiosks are housed in pre-existing Gender Resource Centres run by these NGOs for women’s empowerment efforts at the community level. The rationale guiding this decision was that these spaces had already been established as ‘women’s spaces’, and therefore, women beneficiaries would not hesitate to come forward to access public information or claim their entitlements.

1.b. Ensuring that a woman facilitator is available in every service delivery kiosk/centre.

The Universal Digital Centres set up by the government of Bangladesh in every local government office in the country, under a franchisee model that enlists local village entrepreneurs, has attempted to enforce this. The initiative guidelines have made it mandatory for every centre to be operated by a male and female entrepreneur, at all times. In a cultural context where prevailing gender norms restrict women from interacting with men who are not family members, this goes a long way in ensuring women’s accessibility to e-services (Genilo 2017)18.

2. Putting in place effective safeguards for accountability under partnership arrangements for e-service delivery

Public Private Partnerships/ PPPs in e-service delivery help government agencies fill in technical expertise gaps, but they could lead to a blurring of accountability lines unless roles and responsibilities for ensuring quality of service delivery at the last mile are clearly defined. Therefore, they need to be backed by partnership agreements with clearly specified safeguards to protect citizen-rights, as detailed in Ingredient 3.3, Unit 2.2.

Also, in the development of the terms and conditions for e-service delivery PPPs, financial efficiency considerations should not be privileged over social inclusion. For example, in many instances, one-stop-shop kiosks are run under Public Private Partnership models where entrepreneurs invest money to run ICT businesses that also provide e-services. In this model, entrepreneurs need to balance their commercial and social imperatives – ensuring profitability of their business, even while providing free services to citizens. However, as research has noted, an overemphasis on financial sustainability may further the exclusion of the most marginalised women from these one-stop-shops (Kurian et.al. 2009)19. To safeguard against this, an appropriate balance should be struck, for example, by putting in place differential service charges based on income level/ economic status of the citizen. The government of Kerala’s Akshaya one-stop-shop programme has implemented this – and has completely waived service charges/ commission for citizens from households below the poverty line.

3. Ensuring that databases underpinning e-service delivery are gender-responsive

Databases underpinning all e-service delivery initiatives should adopt gender inclusive taxonomies, to ensure that women are not inadvertently excluded. This has been demonstrated effectively in eKasih, the national poverty databank of the government of Malaysia. This portal aims at supporting effective inter-ministerial coordination for the roll-out of poverty alleviation programmes, by enabling the creation of a comprehensive database of the profiles of all low income individuals in the country..

To enroll on eKasih, individuals need to approach the state/federal level poverty eradication unit and provide their contact information. After validation of an applicant’s poverty status through local level verification mechanisms, s/he is enrolled on the eKasih database, at which point s/he is eligible to claim entitlements under poverty alleviation programmes. The eKasih database has adopted gender-inclusive definitions for ‘applicant’ and ‘poverty status’. Firstly, it allows the enrollment of any member of a household in his/her individual capacity, and not just the head of the household. Secondly, it considers individual income and not just aggregate household income when determining an applicant’s poverty status. This is a major breakthrough, as eKasih has managed to move away from the dominant gender-neutral approach to poverty alleviation, which assumes that targeting the head of the household will automatically lead to the trickle down of benefits to women members.

Unit Summary

Gender-responsive e-service delivery is about ensuring that e-service delivery systems expand women’s access to public information, welfare benefits and economic resources. This requires attention to two main aspects:

- designing e-services targeted at women, that address their specific needs and priorities, accounting for the particular social, cultural and historical disadvantages that they face.

- bringing a gender perspective to the roll-out of all e-services.

i. Designing women-directed e-services is about:

- Building a convergent basket of public services for women, organised along a ‘life cycle’ approach. This calls for attention to user-facing and government-facing aspects of design. On the user-facing end, strategic design of one-stop-shop portals and/or stand-alone web portals for specialised services directed at women becomes critical – to enhance accessibility, ease of navigation, and customised service delivery experiences. On the government-facing end, this requires robust back-end information and data architectures that support inter-departmental coordination and responsive re-programming of services to keep pace with shifts in target group preferences.

- Creating an e-service delivery system that is geared towards promoting rights-and empowerment-agenda. This requires investment in ICT-enabled initiatives that expand women’s access to information and knowledge, promote women’s enterprise and their access to economic opportunities, and provide crisis support. Appropriate institutionalisation of such initiatives within government and context-appropriate design are essential for sustained and effective impacts.

ii. Bringing a gender perspective to the roll-out of all e-services is vital for effective uptake by women. Some strategies that have been very effective in this regard are:

- Setting up one-stop-shop kiosks/ e-service delivery centres in spaces that are perceived as non-threatening by women; and recruiting and training women from the local community, in gender-responsive facilitation.

- Putting in place guarantees for women’s inclusion and safeguards for accountability, in public private partnerships in e-service delivery.

- Ensuring that databases underpinning e-service delivery have gender-responsive taxonomies, to prevent inadvertent gender-based exclusions.

- 1 UN GA. (2012). Resolution on Women and Political Participation. Retrieved from http://www.minaslist.org/library-assets/res-b-25.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 2 ITU. (2016). Action Plan to Close the Gender Digital Divide. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/action/gender-equality/Documents/ActionPlan.pdf, 22 August 2017

- 3 Partnership on Measuring ICT for Development. (2014). Measuring ICT and Gender: An Assessment. Retrieved from http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdtlstict2014d1_en.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 4 UNDESA. (2016). United Nations E-Government Survey 2016. Retrieved from http://workspace.unpan.org/sites/Internet/Documents/UNPAN96407.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 5 McConchie, J (2016). E-government for Women’s empowerment: State of Art Review, Australia. Retrieved from http://egov4women.unescapsdd.org/country-overviews/, 5 September 2017

- 6 Kim, J. (2016). E-government for Women’s Empowerment: State of Art Review, Republic of Korea.Retrieved from http://egov4women.unescapsdd.org/country-overviews/, 5 September 2017

- 7 UNDESA. (2010). United Nations E-Government Survey 2010. Retrieved from https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/portals/egovkb/documents/un/2010-survey/complete-survey.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 8 NSW Department of Industry. (2016). WON NSW Women Entrepreneurs Network. Retrieved from http://www.wonnsw.com.au/idea1, 5 September 2017

- 9 GSMA. (2015). Women & Mobile: A Global Opportunity. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GSMA_Women_and_Mobile-A_Global_Opportunity.pdf, 5 September 2017; DIMAGI. (2016). The CommCare Evidence Base for Frontline Workers. Retrieved from http://www.dimagi.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CommCare-Evidence-Base-July-2016.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 10 Burrell,J. (2015). How to support smallholder and women farmers with ICT4Ag. ICT4D: Tech Research Brief #1. Retrieved from https://markets.ischool.berkeley.edu/files/2015/06/mobile_ag_advice_ucberkeley.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 11 Developed in partnership with Sri Lanka Telecom Mobitel and financial support from Commonwealth of Learning

- 12 Wanasundera, L. and Herath, A. (2017). The E-Government Institutional Ecosystem in Sri Lanka from a Gender Perspective: A State-of-Art Analysis

- 13 Press Information Bureau (2016, December 29). Year End Review: Ministry of Women & Child Development. Retrieved from http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=155963, 5 September 2017

- 14 See Wegate portal, https://www.wegate.eu/who-we-are. accessed on 5 September, 2017

- 15 ABD. (2014). Using Information and Communication Technology to Support Women’s Entrepreneurship in Central and West Asia. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/42466/using-ict-womens-entrepeneurship-central-west-asia.pdf, 5 September 2017

- 16 Lakshane, R.,& Chinmayi, S.K. (2017) Evaluating Safety Buttons on Mobile Devices: Preview. Centre for Internet and Society. Retrieved from https://cis-india.org/raw/evaluating-safety-buttons-on-mobile-devices-preview, 5 September 201

- 17 UNESCAP. (2016). E-Government for Women’s Empowerment in Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/resources/e-government-women%E2%80%99s-empowerment-asia-and-pacific, 5 September 2017

- 18 Genilo, J.(2017). Egovernment for women's empowerment: A state of art analysis of Bangladesh

- 19 Kurian,R., & Ray,I. (2009). Outsourcing the State? Public–Private Partnerships and Information Technologies in India. World Development,20(10). Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Outsourcing-the-State-Public-Private-Partnerships-KURIYAN-RAY/a2bde370d28f89ec38388c2a518cd6f762b4938d, 5 September 2017

Glossary Text for Tooltips

Intersecting structures of social stratification

This concept is used to describe the phenomenon of how individuals simultaneously experience the effects of different hierarchies that operate in society, such as gender, class, caste, race, and ethnicity. These hierarchies are also termed structures of social stratification, and their compound effects shape a person’s social status.

Proximity government

The idea that government should be closer to citizens. In other words, a government that is involved in bottom-up, inclusive and participatory service delivery and public decision-making.

Open Design

This term has been used to refer to transparent and participatory design approaches in e-service delivery and e-participation systems.

convergent service delivery

This refers to a situation where a citizen is able to access public information and government services at a single point – whether a physical kiosk or a virtual portal.

Infomediaries

This refers to frontline workers of government agencies or volunteers who are engaged in addressing public information queries and supporting entitlement processing requests of community members, at service delivery kiosks or telecentres run by state agencies.