1 Overview

This document provides an overview of the case studies undertaken as part of this study of e-government initiatives in the Asia-Pacific. In each of the five countries that were covered by the study (Australia, India, Fiji, Philippines and Republic of Korea), two to three case studies were undertaken in the area of ‘e-government for women’s empowerment and gender equality’ between December 2014 and May 2015. The case studies were undertaken by country consultants1 in each of the five sites of study, identified through an open call issued by UN ESCAP.

1.1 Case Selection Criteria

1. The study included cases of government-led initiatives based on at least one of the following criteria:

- Initiative has a vision/mandate for women’s empowerment and gender equality.

- Initiative has sought to mainstream gender in its core strategies.

- Women are a large proportion of beneficiaries the initiative caters to.

2. Government-led initiatives refer to both initiatives that are completely owned and operated by state agencies as well as initiatives implemented by state agencies through partnership arrangements with private sector and civil society organizations.

3. Cases were selected for good practices in at least two of the three critical dimensions of the e-government institutional ecosystem: service delivery, citizen uptake and connectivity architecture.

The case studies covered are detailed below:

|

Initiative has a vision/mandate for women’s empowerment and gender equality |

|

|---|---|

|

Australia |

Our Watch, State Government of Victoria and Commonwealth Government of Australia |

|

India |

IVR Reporting System for Gender Based Violence (GBV) of the Society for Elimination of Rural Poverty (SERP), Government of Andhra Pradesh, India Sreesakthi Portal of the Kudumbashree Programme, Government of Kerala, India |

|

Republic of Korea |

Cyber-mentoring Initiative, Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, Republic of Korea Safe Return Home Mobile App, Ministry of Security and Public Administration, Republic of Korea Sex Offender Alert, Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, Republic of Korea |

|

Fiji |

mWomen e-service, Department of Women and Vodafone, Fiji |

|

Initiative has sought to mainstream gender in its core strategies |

|

|

Philippines |

Blended Learning Programme of the TESDA Women’s Centre, Philippines |

|

Women are a large proportion of beneficiaries the initiative caters to |

|

|

Australia |

SA Community, Government of South Australia |

|

Philippines |

Grievance Redress System of the Pantawid Pamiliyang Pilipino programme, Department of Social Welfare and Development, Philippines Community eCentres in the Municipality of Malvar, Philippines (CeCs) |

|

Fiji |

Community Telecentre Initiative, Fiji |

In Fiji, the criteria were relaxed since there were very few initiatives that mapped clearly onto the research criteria despite consultation with multiple stakeholders. Therefore, based on key informant interviews, a pilot initiated by a private-sector agency in partnership with the Ministry of Women, and the Telecentres programme of the Government of Fiji were selected as the closest fit.

1.2 Analytical lens used in the case studies

Selected case studies/ initiatives were examined through the lens of institutional analysis to unpack the norms, rules and practices of service delivery, citizen uptake and connectivity architecture underpinning them respectively, using the framework provided in Table 1. This approach was adopted to tease out elements of replicability in the good practices on gender-responsive e-government policy and programming.

2 Initiatives with a Vision/Mandate for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality

2.1 Our Watch, Australia

Country consultant: Jan McConchie

Figure 1

Screenshot of Our Watch portal

1. Overview

Our Watch is a not-for-profit organization that was set up by the Victorian state government and the Commonwealth Government of Australia in 2013 to facilitate a “sustained and constructive public conversation with the aim of improving the public’s awareness of violence against women in Australia, ...growing the primary prevention movement...and encouraging people to take action to prevent violence against women and their children.”2

Our Watch uses a combination of traditional and new social media outreach and community events, to create an alternative discourse on gender and sexuality, and break the silence on domestic violence. Currently, it has undertaken the following projects:

- A national media engagement project funded by the Commonwealth Government to improve reporting through media capacity training, website based resources, a national award scheme and a national survivors’ media advocacy program.

- A digital communications strategy on preventing violence that uses a range of social networking tools and social media platforms (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, and a blog on the Our Watch website) to target parents, teachers, family violence sector workers and media about the urgency of the issue.

- A social media service that enables survivors of domestic violence to share their stories, with empathetic listeners.

- The Line, a primary prevention youth-oriented social marketing campaign, initially developed by the Commonwealth Government, focusing on changing attitudes and behaviours that condone, justify and excuse violence against women by engaging young people in the age group of 12 to 20 years.

- Respectful Relationships education in Secondary Schools in Victoria supporting up to 30 schools to deliver new curriculum guidance, and embed a ‘whole of school’ approach to promoting respectful relationships.

- Strengthening hospital responses to family violence in two Victorian hospitals to ensure that doctors, nurses and other staff know how to respond confidently and sensitively when they treat women and their children who have experienced violence.

- Partnering with local organizations to develop tailored violence prevention programs for two culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Victoria.3

- Pushing for support for the iMatter App developed by the NGO Doncare that explains the connection between certain types of behaviour and abusive relationships. This is seen as extremely critical to expanding the Our Watch communication strategy, in a context where over 22 per cent of young women under the age of 20 have experienced domestic violence.4

2. Insights on creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Flexibility offered by a non-traditional organizational structure: Our Watch has adopted a non-traditional organizational structure — that of an independent non-profit company limited by guarantee, with an independent board.5 Its funding is secured through partnerships with federal and state governments. Accountabilities are ensured through funding agreements, protocols and strategies with the respective government agency providing financial support. This arrangement has helped Our Watch function independently, without political interference in everyday functions, and yet be assured of continued financial support.

Emphasizing continual involvement of citizens in design: For a programme that works on preventing VAW, ‘messaging’ effectiveness is crucial. Our Watch has adopted a new-age approach markedly different from traditional public information broadcast that views citizens as passive beneficiaries. The approach adopted by Our Watch fosters dialogue with, and among, survivors of violence and youth, through the strategic use of social media. User feedback is periodically collected and the tools are reviewed. Emphasizing iterative design that is constantly responsive to citizen feedback has helped in enhancing the relevance of the messages and campaign-content developed by the initiative.

A concrete example of the effectiveness of this approach is evidenced in The Line campaign, which has stayed away from prescriptions. The campaign ensures that young people can identify with the language and content, encouraging them to ‘call out’ instances of VAW and other abusive behaviour. An evaluation of the campaign demonstrated that when young people are exposed to The Line, they are more likely to understand what behaviours ‘cross the line’ and are more likely to make positive changes to their behaviour than otherwise. In the future, Our Watch plans to strengthen The Line by constituting Youth Digital Committees to ensure that the content, tone and themes of the campaign continue to stay effective and relevant.

Due cognizance of privacy: Our Watch has clear safeguards to protect participants using its online discussion forums. These forums are the key spaces where VAW survivors seek peer support and share their stories. At present, these spaces are public, though discussion is moderated. But Our Watch is currently exploring the possibility of setting up closed discussion forums where anonymity is safeguarded.

Addressing equity considerations: By deploying a range of social media technologies, Our Watch reaches those accessing the service from low speed connections. Our Watch recognizes that discursive shifts can be achieved only through a strategy that combines social media campaigns with traditional media engagement. A lot of effort has hence been put into developing media partnerships, traditional and non-traditional media events, and engaging editors and academics of influence in the field, as part of the National Media Engagement project. Among these efforts, the Media Campaign on Sensitive Reporting of GBV stories from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities deserves special mention, as it focuses on sensitizing journalists to avoid stereotypical reportage of non-mainstream cultures.

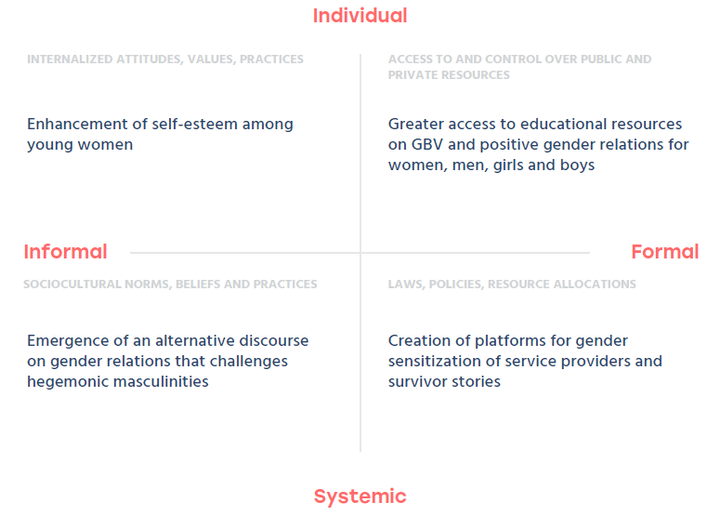

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

Our Watch has aimed at transforming deep-seated cultural norms and attitudes in communities so that the culture of silence around violence against women and children is broken. The social media strategies of Our Watch seem to have been especially successful in this area. The social media space for women survivors of violence has helped them forge networks of support where they can narrate their stories.6 The Line campaign has led to a shift in attitudes towards VAW among participants, as more and more youth exposed to the campaign have started calling out instances of behaviour that crosses the line (i.e., abusive or disrespectful behaviour).7 The iMatter app has contributed to promoting self-esteem and confidence among young women by educating them about disrespect and intimate partner violence and promoting conversations about healthy relationship behaviour.

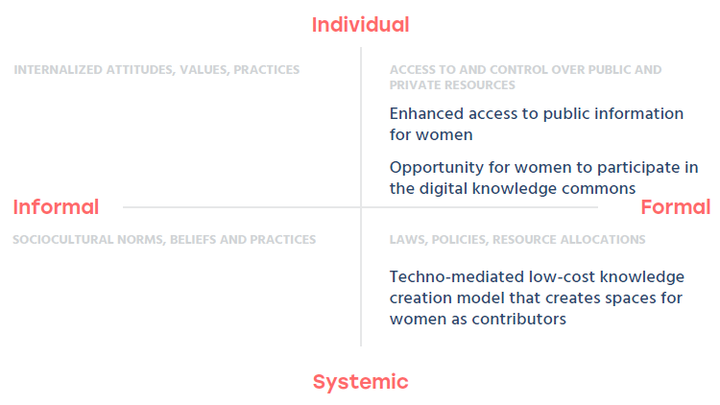

Figure 2

Analysis of Empowerment Outcomes of Our Watch Using Gender at Work Framework

2.2 IVR-SERP, India

Country consultant: Nandini Chami

1. Overview

The Society for the Elimination of Rural Poverty (SERP) was set up by the Government of Andhra Pradesh, India, in the year 2000 to address rural poverty through social mobilization and empowerment of poor women and skill development. SERP constituted women’s self help groups at the village level, with a federated structure at the block8 and district levels, and equipped them with access to income generation and livelihood opportunities. In this process, the functionaries of SERP realized that the economic empowerment of women could not be achieved by these pathways alone, unless underlying structures of gender-based discrimination and violence were tackled head-on.

Therefore, in 2008, Social Action Committees (SACs) were constituted at village, block and district levels, comprising representatives from the self help groups. SACs were entrusted with the responsibility of addressing in their local communities rights education for adolescent girls as well as critical instances of gender and social injustice such as domestic violence, human trafficking, sexual assault and child marriage. The idea behind this three-tier SAC structure was to create a mechanism for enabling marginalized rural women to challenge the prevailing culture of silence around violence against women and gender based discrimination in their communities, by using other women like themselves as a peer support network.

2. How SACs further the fight against GBV and rights-violations

All incidences of rights-violation identified by SAC members are brought to the notice of the village level gender forum and registered as ‘cases’. In instances where home-visits are not fruitful, gender forums refer the affected parties to the family counselling centres managed by block-level SACs. The block-level SACs are linked to crucial linedepartments and the police force and draw on their support.

Cases where intermediation and counselling fail are referred to the district-SAC which facilitates access for the affected women to the Free Legal Aid Cell and the Lok Adalat (People’s Court — an official alternative dispute resolution system in India) set up by the state.

3. Factors that led to the development of the IVR reporting system

Historically, a manual reporting system was adopted by block-level and district-level SACs. As the work of the SACs expanded, a number of shortcomings in this manual reporting and tracking mechanism started becoming evident. It was difficult for the district gender anchor officer to track pending cases or ascertain that pending cases were not dropped accidentally.

Therefore, in 2012, an IVR based reporting and monitoring mechanism to track and provide on-going support to block and district SACs in a more effective manner, was conceptualized by the State Project Management Unit. The IVR system seeks to do the following:

- Enable a voice-based reporting and monitoring system for cases handled by SAC members, and timely support and guidance from SERP functionaries (at the district level), especially in cases which have encountered bottle-necks at the stage of seeking legal assistance.

- Provide informational services to SAC members on issues such as women’s rights guaranteed by various statutes and laws, legislative changes and other dimensions of legal and rights literacy.

To implement this proposed idea, in 2012–2013, Evolgence IT Systems Pvt Limited was identified through a formal tendering process as the technology service provider for the initiative. Between 2013–2015, using the Asterisk Open Source Platform, Evolgence has designed part of the call-in functionality for reporting that was conceptualized by the founders of the initiative, and rolled it out across the state. The broadcast functionality is yet to be developed.

In its present form, Evolgence’s system enables recording of cases by SAC members at only 2 stages; at the point of registration and at closure. A case is considered as closed/resolved when the affected party (a woman or child who has suffered a rights-violation) is satisfied with the redress received through informal intermediation by SAC members, counselling and/or legal intervention. Users can call in or give a missed call to the IVR number to utilize the call-back option from the system in order to record their report. At the registration stage, SAC members who call in are required to record the specifics of the case on the voice call, and then note down the unique case identity assigned by the system, before disconnecting the call. Using this number, they call again to report closure, upon resolution of the case.

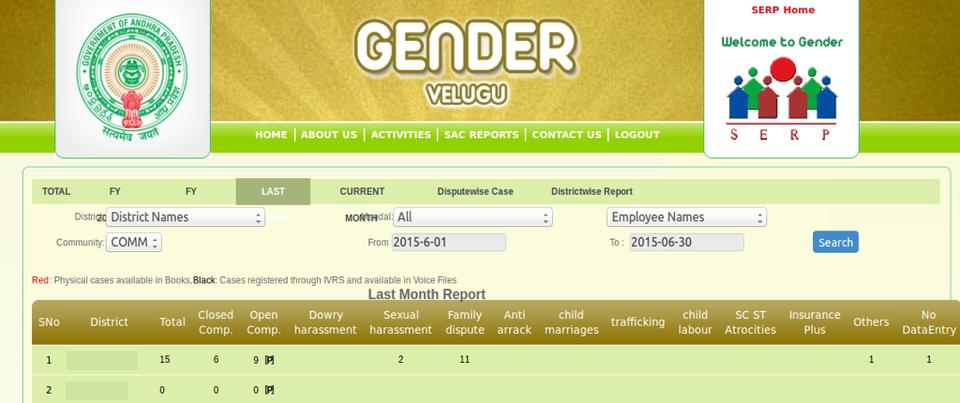

Currently, the reports of case registration and closure that are received through the IVR system are transcribed at a centralized location (Evolgence’s office) by data entry operators. They are then published on a web application that Evolgence has developed for SERP. Though data entry and modifications are password-protected processes, the data published is accessible to all, and not just to SERP functionaries. The web-application enables effective internal tracking of pending cases within the Gender Unit of the State Project Management Unit (SERP). The consolidated data can be sorted in multiple ways (by district, across districts by time-period, by type of disputes) as well as accessed for specific, individual case reports (case details in text format, the audio files about registration and closure). Members of the public can view the published case reports by accessing the web-application through the official website of SERP.

Figure 3

Web-based case register (Summary of cases)

Figure 4

Individual case reports available online

4. Insights on creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Predictability and citizen trust: The data architecture of the IVR system enables easy identification and tracking of pending cases and comparisons of district-wise data. The system has reinforced an ethos of accountability among district SERP functionaries regarding pending cases in their jurisdiction.

Effective management of PPP arrangements: SERP has a streamlined process of entering into Public Private Partnerships for ICT interventions. In particular, it has a separate IT Division that takes care of drawing up the contract for terms of service, and the MoU with the private partner. The Director of the IT division works closely with the respective functional director (gender/livelihoods/agriculture) of SERP’s wider programmes to review the performance of the technology service provider. The normal practice in SERP is to issue contracts for 3 years, at the end of which the performance of the private sector partner is reviewed and a decision is taken about whether the relationship can be continued. In the case of the contract with Evolgence Systems Pvt Ltd for the IVR programme, these norms have been applied.

Technical openness: Open standards and the question of interoperability in all its ICT initiatives is currently a key priority at SERP, and the IVR system is also built accordingly on the Asterisk Open Source Platform.

Transparency: Transparent reporting of all its efforts is a core value at SERP. All the details of the cases that come to the notice of the SACs, including names and addresses of complainants, are published online. Voice calls are available for all cases except instances of sexual abuse/violence. Making information public is a decision on the part of the programme to “break the taboo around reporting GBV in a rural context where a woman comes forward to make public a violation or abuse normalized by the culture.” 9

Equity considerations: A separate field for recording the victim’s caste has been included in the IVR-based system, to ensure priority tracking of cases of rights-violation of women from marginalized socioeconomic groups whose rights are protected through special laws.

Making the IVR and its objective familiar to rural communities: When the IVR system was introduced in 2012, a Master Trainers’ programme was conducted by the Evolgence team and the gender team members of the State Project Management Unit of SERP. Five SAC members from every district got trained and they went on to train other SAC members in their respective districts. Thus, through this cascade model, it was ensured that all SAC members were familiar with the digitalized reporting system.

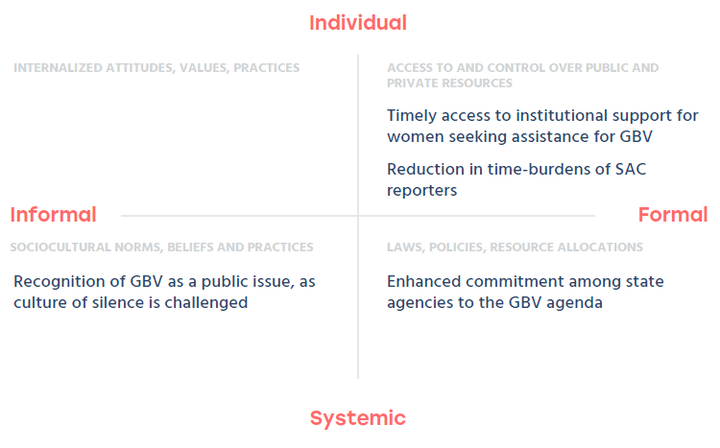

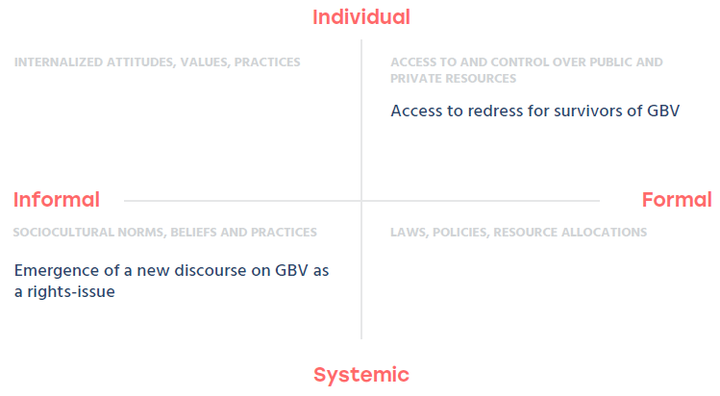

5. Impacts on Women’s Empowerment

The IVR system has contributed to SERP’s attempt to help survivors of GBV and Social Action Committee members in making gender issues legitimate public concerns. The systematic tracking and publishing of information about the incidence of GBV that the IVR system has enabled also helps in increasing the accountability of state agencies towards addressing this issue.

SERP functionaries at the State Programme Management Unit feel that the enhanced effectiveness in case-tracking of GBV enabled by the IVR has strengthened the efficiency and responsiveness of the SERP system to cases of GBV. Another advantage that they perceive is that the current IVR functionality of ‘call-in and file case reports’ reduces the time burdens of SAC members.

SERP functionaries at the district level feel that the IVR mechanism has some potential to contribute to individual empowerment of SAC members, especially if additional functionalities are introduced. Plans to send out information and thought-provoking messages on the IVR about gender discrimination, VAW and related issues are underway. A call-back functionality for SAC members to file reports of issues that come up in the gender trainings they conduct at the village level for adolescent girls or key campaigns they undertake is also on the cards.

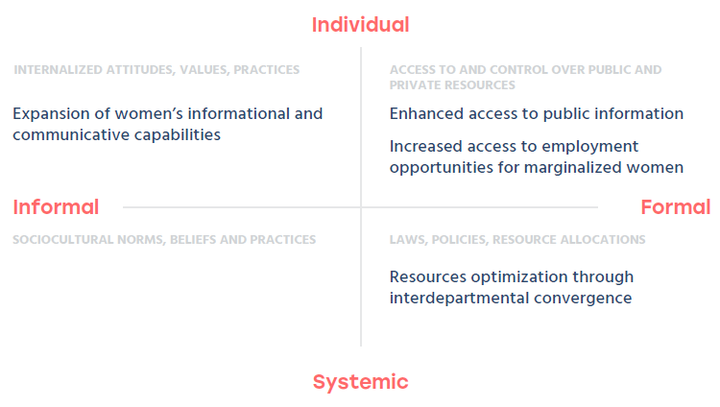

Figure 5

Analysis of Empowerment Outcomes of Ivr-Serp Using Gender at Work Framework

2.3 Sreesakthi Portal, India

Country consultant: Nandini Chami

Figure 6

Screenshot of SreeSakthi portal

1. Introduction

Sreesakthi is a government-led portal that aims at using the ICT-enabled networking opportunity for bringing marginalized women across the state of Kerala, in South India, onto a discussion and learning platform. The initiative was introduced by the Kudumbashree State Poverty Eradication Mission, an independently registered society set up by the state government of Kerala for poverty alleviation and women’s empowerment. Kudumbashree works through a collectivization and community networking approach, setting up village-level women’s self-help groups organized under a three-tier structure: neighbourhood groups of 20 to 25 women from each locality as the foundation, federated into Area Development Societies at the electoral ward level and Community Development Societies for each rural and urban self-government unit (known as Gram Panchayats/Municipalities in India).

The Sreesakthi Portal was launched in 2010, with the primary objective of providing a web-based ‘open space’ for Kudumbashree groups across the state. Its stated goal is to shape gender discourse by challenging “received gender-norms”. It seeks to strengthen peer solidarities of geographically dispersed women’s collectives, by providing them a space to share reflections and insights in a manner that unpacks gender discrimination and enables new imaginations of society, based on equality and justice. The secondary objective was to provide a moderated platform for women to engage in online debate and dialogue with local leaders, and other community members, thus encouraging women to develop critiques of mainstream gender discourse.

The portal was developed in English and Malayalam (the local language) and funded by the Department of Electronics and Information Technology, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India (DeiTY, MCIT). Technical support was provided by the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC) — a governmental agency set up by MCIT and entrusted with the task of building capacities in emerging/enabling technologies for providing IT solutions to different sectors of the economy, particularly in e-government initiatives.

The Sreesakthi web portal is first and foremost, a discussion forum for Kudumbashree’s Gender Self-Learning Programme that focuses on developing critical gender perspectives among women’s groups, through a participatory training process that breaks away from traditional top-down classroom models.

The State Gender Team initiates discussion on the portal. Comments are posted based on moderation in which the technical consultant/the portal administrator, the gender consultant and the Programme Manager of Kudumbashree participate. Comments that are libellous or politically sensitive are not posted — and the reasons for not publishing comments are explained to the concerned user over email. When the discussion has plateaued out (usually after 2 to 3 months), the thread is closed. Training modules are then finalized, and through a cascading model, transacted with neighbourhood groups. Discussion threads that enable women to share training experiences are then opened up on the portal. Currently, a module on the issue of ‘Women and mobility’ is being developed — and discussion threads on this are open on the web portal.

Though the primary target audience of the web portal are the grassroots members of the Kudumbashree programme, membership is not restricted to the Kudumbashree women’s network. Any interested individual, residing in Kerala or outside, can participate in these online discussions, after registering on the portal and following a simple authentication process.

The portal currently has 13,089 registered users with 55,200 posts in the discussion forum. At least 5360 users are women members from the Community Development Societies of the network.10 There have been 21 discussion threads till date, on topics pertaining to women’s rights, health, women and work, environment and education.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Online dialogue for building collective capabilities of women’s collectives: The portal uses online dialogue strategically to build a bottom-up gender mainstreaming model, in which economically marginalized women are seen as equal participants rather than as recipients of expertise provided by resource persons. Women members are not just approached for feedback and comments on pre-selected themes for training, but training ideas themselves are drawn from key issues/concerns discussed online. Secondly, the portal, because of its embedding in group-based face-to-face learning processes, also encourages the sharing of collective reflections and feedback — facilitating women’s collectives to use the online space to share and connect.

Connectivity backbone: Programme founders ensured that women’s groups who were part of the programme had free access to computers and the Internet at the offices of the programme’s Community Development Societies, before launching the web portal. Thus, adequate care was taken to provide a free and safe space for women to access the online platform. This was important, considering that women targeted by the programme are economically disadvantaged, and public access points are male-dominated spaces.

Moderation of online platform: Content is posted on the portal only after it is vetted by members of the State Gender Team of the Kudumbashree State Mission Office. The norms for content-vetting are decided by the State Mission Office. Moderation has an important role to play on public platforms where pro-women discussions could attract trolling and harassment.

Mechanisms for strengthening uptake: The training strategy of 10 to 15 women members from the Kudumbashree network in each district, as Master Trainers for the Sreesakthi Portal, has been an extremely crucial strategy for enhancing uptake of the portal. These trainings served not only as an introduction to basic digital skills for participants, but also as a means of higher order use of the Internet — as a space for peer sharing and deliberation. The strategy of using peer trainers rather than external experts for digital literacy and capacity-building has enabled better contextualization and localization.

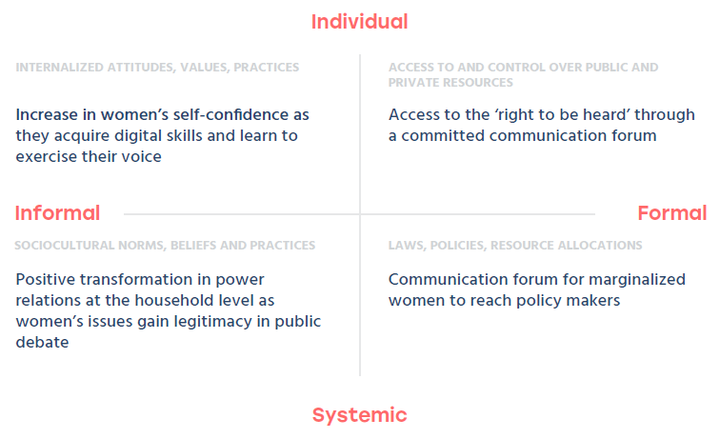

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

This initiative has demonstrated how ICTs can be effectively leveraged by governments to foster citizen-participation of marginalized women. It recognizes that this involves moving beyond the skills-training paradigm to investing in new cultures of use that enable women to leverage digital technologies for strengthening their capabilities for public participation.

The Sreesakthi Portal has contributed to participants’ sociocultural empowerment at multiple levels. At the individual level, it has contributed to increase in women’s skill building and self-confidence, through training programmes for digital literacy and use of the portal to express themselves. At the household level, field work for the case study points to multiple gains for women — ranging from enhancement of status due to their newly acquired digital skills-sets, to an increase in their negotiating power with other family members, and capacity to question discrimination and violence within the household. As one woman member from the Kudumbashree network shared during a Focus Group Discussion carried out for this research,

“Earlier women were cloistered and alone in their households — and had nowhere to turn to, when they faced violence and harassment. The portal provides them a space in addition to their immediate neighbourhood group where they can come out in the open about these problems, and seek help. Women no longer need to be quiet. The portal makes individual experiences of violence public and connects women to many other women who are their peers. This helps in reducing household-level abuse.”

At the community level, the portal has played a key role in opening up women’s access to institutional support. In one instance, when a woman who was facing domestic violence did not receive any support from the local police when she went to file a complaint, she wrote about her predicament on the portal. The Minister in the state government who is in charge of Kudumbashree read her post and immediately intervened, and also urged other women in similar situations to speak out.

The portal has also strengthened the translocal solidarities of the geographically dispersed groups of the Kudumbashree programme. As one woman participant reflected:

“The portal has become as important to us as mobile phones are (to most people). Now what will happen if you lose your mobile? You can’t express your emotions quickly to the people who matter, and you cannot bridge distance to communicate across geographies. This portal helps us talk to our peers in Kudumbashree in other districts, and engage with their thoughts — and this is very important.”

Figure 7

Analysis of Empowerment Outcomes of Sreesakthi Portal Using Gender at Work Framework

2.4 Cyber-Mentoring Initiative, Republic of Korea

Country consultant: Jung-soo Kim

1. Introduction

The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, Republic of Korea launched a cyber-mentoring service directed towards women, on its web portal ‘Women’s Net’ in 2002, with the objective of enabling women to seek guidance and support for their career development. The specifics of how this service works are detailed below.

Young women who have just graduated from high school and college, and those with less than 3 years of work experience can register themselves as mentees. Women with more than 3 years of work experience can apply to be mentors, and they are asked to submit online certificates and other documentation as proof of their credentials. At the time of registration, mentees are required to enter their personal information along with details of the nature of work experience, interest areas etc. Once their registration form has been approved by the system operator, mentees can log in to the web portal and view profiles of registered mentors, and then apply to specific mentors (whose work and interests match theirs), seeking acceptance for mentoring. Mentors, when they log in to the portal, can go through the list of mentees who have sent requests to them, and accept or reject applicants, according to their preferences. When a mentor and a mentee have been matched, a private online space where the pair can converse, is opened up on the portal. Mentors and mentees can interact with each other, for a period of 60 days. The mentoring arrangement can be renewed twice, at the mentee’s request, within 2 weeks after the end of the first mentoring — and thus the maximum mentoring period is 180 days.

For the day to day management of the cyber-mentoring web portal, an implementing agency is selected by the Ministry for Gender Equality and Family through a process of an open call for tenders. All national agencies and organizations with expertise in the area of gender training and awareness generation about women’s rights are eligible to apply. At present, the implementing agency is the Korean Institute of Gender Equality Promotion and Education (KIGEPE).

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Shifts in mentoring cultures: The flexibility with respect to time and space that cyber-mentoring brings has opened up new opportunities in teaching-learning for women, giving them new options amidst their multiple time burdens.

Connectivity backbone: The initiative is able to reap the benefit of near-universal connectivity and negligible gender gap in Internet access for the target group of 20–30 year olds.

Privacy: When mentors and mentees sign up, they are required to abide by a code of ethics that prevents the disclosure of any personal information/content made known during the cyber-mentoring process. Such formalization is a useful measure of quality in such online interactions.

Optimizing stakeholder arrangements in delivery of service: The initiative has acquired a lot of maturity over the years, in terms of the forms of stakeholder arrangements it adopts. In the initial years, an IT agency was contracted as the implementing agency. However, over time, it was realized that it is more productive to have a women’s rights organization in this role. Similarly, partnerships with the Career Development Centres at Universities have been formalized through contractual arrangements, to ensure that convergences between such centres and cyber-mentoring are strengthened.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

There is evidence of the empowering impacts of the service from previous research11 and the Sisterhood Diaries12 maintained by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in which the testimonials of mentors and mentees have been recorded. For the mentees, the pyschological support provided by the cyber-mentoring relationship seems to have restored self-confidence, expanding their vision about their careers, and allowing them to step out of the box of prescribed gender roles. As one mentee reflected:

“At the start of this year, I was distressed that my dream was to become a soap drama playwright. I was alone as most of my university friends were pursuing careers as office workers or thinking about studying at a graduate school, while those who studied drama with me were from a different age group. My mentor, (herself a senior playwright), helped me to ask myself why I wanted to be a playwright and what I really wanted. She gave me a lot of advice. I realized what was really bothering me, and the answer came out very easily.” 13

For the mentors, the rewards of being involved in cyber-mentoring are psychological, including satisfaction at having contributed to someone’s self-development, and an opportunity for personal growth.

Figure 8

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF CYBER-MENTORING INITIATIVE USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

2.5 SAFE RETURN HOME MOBILE APP, REPUBLIC OF KOREA

Country consultant: Jung-soo Kim

Figure 9

Safe Return Home interface

1. Introduction

The Safe Return Home mobile app has been developed by the Ministry of Security and Public Administration, Republic of Korea, to enable women to take precautionary steps to safeguard themselves, by keeping their friends and family members informed about their whereabouts.

The application has three key features:

- Upon installation and registration, it allows users to share the details of their geo-location in real time with select contacts, via text messages or SNS platforms.

- Users can intimate their key contacts when they have to pass through certain areas that they consider to be high-risk neighbourhoods, as the app has a feature for sending auto-notifications to key contacts when the user passes through areas that she has marked as ‘dangerous’.

- The app provides information about key emergency services such as hospitals/clinics, pharmacies, police station, fire station, emergency shelters etc.

In 2007–2008, the Ministry of Public Administration and Security (since renamed the Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs) as part of its Informatization Strategic Plan on combining administrative information with geographic information, joined hands with the Ministry of Land, Transportation and Maritime Affairs, in developing an integrated national geographic information system. More recently, a governmental decision was taken to open up this data to the public as part of a larger push towards informational transparency in the movement towards Government 3.0. This has been a key driving force in enabling the development of the Safe Return Home mobile app.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Interagency partnerships crucial for cutting edge ‘data in governance’ initiatives: This initiative demonstrates the benefits that e-government can bring, through promoting effective interagency partnerships. Its very inception was made possible through inter-ministerial cooperation. The day to day implementation is managed by the Korea Local Information Research & Development Institute with overall supervision from the Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs, and expertise from the National Information Society agency.

Bringing the benefits of open data to citizens: Safe Return Home app testifies to the personalization capabilities that Government 3.0 offers. The initiative allows the geographic information database to interact with user-specific data in a way that responds to women’s physical and psychological security needs.

Public participation in implementation of service: A consultative committee comprising representatives from the public and private sector and academia is involved in an advisory role in the initiative. User feedback on the features of the app is actively solicited.

Promoting citizen uptake: Efforts for promoting Safe Return Home mobile app are made in different ways. One strategy involves partnering with metropolitan and provincial Offices of Education. The Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs sends out information on the app via school newsletters addressed to parents. The Ministry also organizes periodic events to collect stories on how citizens are using the mobile services.

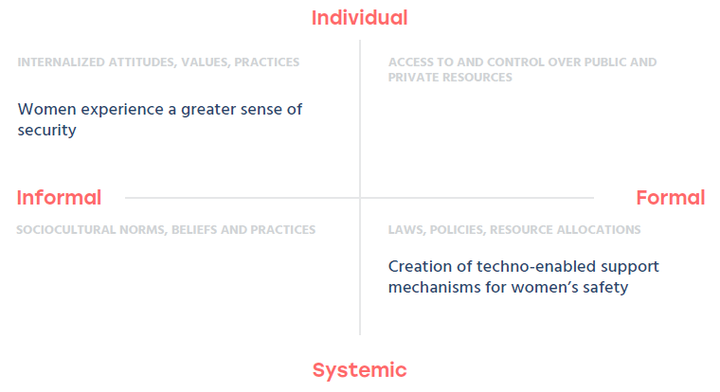

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

At the individual level, the initiative contributes to the psychological well-being of women and young girls who use the service, by enhancing their sense of security and safety. At the sociocultural level, the initiative enables individuals to leverage their social networks in times of distress/emergency.

Figure 10

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF SAFE RETURN HOME USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

2.6 SEX OFFENDER ALERT, REPUBLIC OF KOREA

Country consultant: Jung-soo Kim

Figure 11

Sex Offender Alert portal

1. Introduction

In 2000, faced with the rising incidence of the trafficking of young girls into the sex trade, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family started the Sex Offender Alert Service to pro-actively disclose details of ‘known’ sex offenders in their neighbourhoods, to members of the public. The service has three components — a website (www.sexoffender.go.kr) on which members of the public can access details of offenders, a mobile application that users can install on their phone to receive alerts, and the mail notification service (including email and postage mail) that alerts subscribers to offenders ‘moving in’ and ‘moving out’ of their neighbourhoods.

The work-flow process underpinning this service is as follows. The court has the authority to determine which cases of sexual offences mandate disclosure about the offender’s personal information, to members of the public. It will notify its judgment on disclosure to the concerned offenders and the Ministry of Justice. Within 30 days of receiving the Court order, offenders are required to register their personal information with their district police office. Following this, every time they change their address, offenders must notify ‘move-in’ and ‘move-out’ details with the concerned police offices, within 20 days. The National Police Agency transfers this information that is compiled by its various district police offices to the Ministry of Justice, and also undertakes a verification-check, once a year. The Ministry of Justice then registers this information on its mass data distribution system; and then shares it with the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family which manages the proactive disclosure systems — the website, the mobile app, and the e-mail notification service.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Responsiveness to citizen needs: Prior to the introduction of the online Sex Offender Alert service, there were offline arrangements that allowed members of the public to access information about the sex offenders residing in their district. However, considering that most sex offenders tend to commit crimes in locations that are removed from their immediate communities,14 the utility of such a ‘district-level’ service was limited. The introduction of the online component has enabled citizens to access a consolidated databank about sex offenders across various regions stay intimated about their movements, and access details of their criminal records. The mail notification service directed towards schools and households with children and youth was initiated in 2012, as a strategy for enhancing awareness about sex offenders among groups for whom such information matters most.

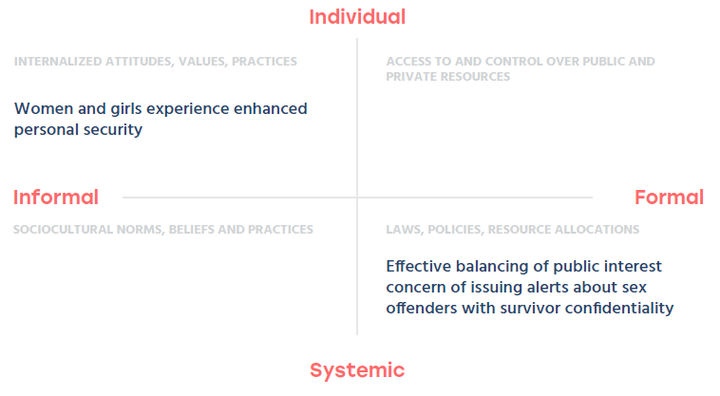

Balancing survivor-confidentiality and public interest concerns of issuing alerts about sex-offenders: The initiative is a good example of balancing public interest concerns (of alerting citizens about sex offenders who pose a risk in their neighbourhoods) with survivor-confidentiality and the right to privacy of sex offenders (to them a fair chance of rehabilitation). Its online information system has a number of checks and balances with respect to identity authentication for data access. Personal information of citizens who use this service is encrypted, and there are clearly specified time limitation clauses for holding the data thus collected. To comply with legal safeguards preventing republication of the information, the software prevents copying/saving of content.

Using the mobile opportunity effectively to enhance accessibility: Mobile applications have more potential to improve accessibility. While the identity authentication process still remains in the case of mobile users of the service, such users do not have to download as many security software programs as required when accessing the service through the website. The mobile app has an additional feature of sending periodic alerts to citizens about offenders in their neighbourhoods.

Commitment from the highest office of government: The service has seen an active involvement of senior offices of government, sending out a clear signal vis-a-vis the priority to eliminate sex crimes. In fact, the impetus for the development of the mobile service was provided by a task force meeting held in August 2012, where it was discussed among various ministries including the Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Strategy and Finance, Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, Ministry of Justice, that a mobile component of the service is required as part of stepping-up efforts towards eliminating sex crimes.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

Research shows that the service contributes to an enhancement of the sense of personal security among young women and girls, as they feel adequately prepared about the ‘risk elements’ in their neighbourhoods.15 However, perceived dangers do not necessarily lead to increase in citizens’ collective responses to create safe neighbourhoods. According to a survey conducted in 2012, most of the respondents (93.5 per cent) who accessed the information on the sexual offenders via a website or a mailing notification took more than one preventive measures after being informed, but their preventive actions tended to be limited to avoidance behaviour16 rather than collective action at community level.17

Figure 12

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF SEX OFFENDER ALERT USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

2.7 mWomen e-service, Fiji

Country consultant: Susanna Kelly

1. Introduction

The mWomen e-service is a subscription-based SMS service offering free advice daily, on women’s and children’s legal rights, family law and gender based violence. It was initiated in March 2013, as a partnership between the Department of Women, Government of Fiji and Vodafone. In November 2013, coinciding with the Fiji government’s new national policy, an additional SMS Counseller component — a free short code number that members of the public can phone to seek legal advice and counselling — was launched. Callers to this service are referred to an NGO, ‘Empower Pacific’, though there is no formal partnership arrangement.

The mWomen service and its SMS Counseller component seek to:

- educate people on options available to address the problem of GBV.

- provide a channel for women to link up with Empower Pacific.

There are currently 25,613 subscribers to the mWomen e-service, of whom 65 per cent are women.

2. Learnings from the initiative

Absence of a formal agreement and dilution of citizen accountability: Absence of a formal agreement between the Department of Women and Vodafone has resulted in a situation where the government’s involvement has tapered off over time, and Vodafone is now the primary driver. For citizens, this means that there is no way they can demand minimum levels of service, and the long-term sustainability of the service is also called into question, as it is highly unlikely that the government will pick up the service if Vodafone ceases its involvement. Similarly, there is no service agreement with the NGO provider of counselling services ‘Empower Pacific’. Public-private partnerships in e-government therefore need to foreground citizen accountability issues from the outset. Service guarantees are vital to secure the rights of the most marginalized. This may be even more significant as services move online without an offline counterpart. At the time of this research, there was one lawyer providing information and sending daily texts to subscribers. This position was paid for 18 months, but is now voluntary (due to the lack of funding support). Further, it was noted the effectiveness of the NGO counselling service enquirers are referred to is hampered by high staff turnover and lack of capacity.

Accessibility barriers: Although mWomen is based on the fact that more women have access to a mobile phone than computers, critical questions remain about the most marginalized/vulnerable women’s access to services provided through mobile phones. Many women lack secure and/or affordable access to a mobile phone, an issue that does come up in the case of other countries as well. Large scale efforts like the Grievance Redress System in the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino programme in the Philippines also point to this problem.

Absence of public data: All data relating to mWomen is collected and managed by Vodafone. Vodafone has not released any usage data (beyond number of subscribers or queries received) and it is not clear what data is collected. Vodafone has stated its intention of conducting a customer satisfaction survey in the future. The lack of information on uptake and results of mWomen reflect an overall low data environment in general, and a lack of sex-disaggregated data collection systems, in particular.

Need for effective publicity and citizen-uptake measures: For the first years of the service, offline promotion of mWomen was minimal. From April 2014, offline mechanisms to promote the mWomen service have included training local community women to advocate for ending violence against women and children. However, there seems to be confusion regarding the service’s target audience — for example, there have been instances of men accessing advice in Domestic Violence Restraining Order cases. Designing for gender equality and women’s empowerment must include clarity of goals and strategies across all levels of e-government.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

The mWomen initiative has the potential for significant impact on women’s knowledge of their rights and the support structures that can help them access these rights, particularly in the context of domestic violence. Greater direction-setting by the government and formal service level agreements with private partners can make a difference, if the government, as a duty-bearer in the context of GBV, can refurbish and implement the programme.

Figure 13

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF mWOMEN USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

3 Initiatives that Have Mainstreamed Gender

3.1 Blended Learning Programme, Philippines

Country consultant: Maria Juanita Macapagal and Mina Peralta

Figure 14

Screenshot of TESDA portal

1. Introduction

The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority in the Philippines (TESDA) was set up in the 1990s to “provide direction (and shape) policies, programmes and standards towards quality technical education and skills development”. TESDA provides technical vocational education and training (TVET) in trade, agricultural and fishery schools across the country, and also collaborates with schools and institutions for accreditation, coordination, integration, and monitoring and evaluation of formal and non-formal TVET programmes. TESDA has set up 15 Regional Centres and 45 Provincial Training Centres in the country, one among which is the TESDA Women’s Centre (TWC). The Women’s Centre is TESDA’s lead training institution for mainstreaming gender and development (GAD) in TVET and sustaining the integration of GAD components into existing technology-based training programmes.

In May 2012, TESDA launched the free TESDA online programme, e-TESDA, with the intention of making TVET more accessible, increasing quality and improving the teaching and learning process through the use of ICTs. The online learning space is an interactive menu with video demonstrations of embedded skills, and the content has been developed to facilitate self-directed learning, as part of which learners can freely navigate across topics. Following this, in 2013, TWC piloted a blended learning programme combining traditional face-to-face classroom training, with online training, in two of its courses — Food and Beverage Services, and Housekeeping. The idea underpinning this initiative was that blended learning rather than just online training would result in more effective learning outcomes for marginalized women, who constitute the majority of trainees in TWC programmes, when compared to online training. It was felt that in addition to online exchanges, classroom interactions would help in enhancing peer support networks, and guidance and mentorship from trainers.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

A human touch to online training programmes: The Blended Learning Programme has responded effectively to women learners’ need for flexible spacing of learning time, peer networking and support, and access to safe spaces for learning. In this model, trainers are available for dialogue during class hours and they also provide additional lessons to those who find the online training inadequate. Trainers can track the frequency of log-ins, monitor their trainees and check on the completion of their online training. These measures make for greater effectiveness of learning outcomes.

Connectivity backbone: TWC recognizes the affordability of Internet connectivity as a key concern for marginalized women. Therefore, the Blended Learning Programme offers spaces at the TWC where women learners can access the Internet for free, and also provides offline versions of the courses — so that even without continuous Internet connectivity, learners can still use downloaded content. Additionally, the Programme Management Unit of e-TESDA is working with the Department of Science and Technology-ICT Office’s iGov and e-Society Programmes to use Community eCentres and public libraries for enhancing access to the e-TESDA online programme.

Open technical architecture: TESDA makes use of open source platforms like Moodle (Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment), in the development of its Internet-based e-learning materials. Technical openness which reduces vendor lock-ins and design costs in e-service delivery, is critical in the transition to digitalized government.

Full subsidy of service to cater to the most marginalized women: e-TESDA provides a free web-based learning programme, based on a no-cost policy that encourages participation of citizens. TESDA has also entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with some companies (Microsoft, Intel and Google) for access and free use of applications by online learners.

Data security measures as per gender mainstreaming rules: To ensure protection of its learners’ information, e-TESDA has adopted the data security measures used by the PREGINET 18 system of the Department of Science and Technology ICT Office. This takes care of data protection, including the registration information of TESDA users. Having an enabling law for gender mainstreaming has helped TESDA in the formulation of institutional data security policy and processes favorable to women.

Gender-responsive programme design: While the e-TESDA programme puts total responsibility on the user to complete the course, the TWC Blended Learning Programme provides a more gender-responsive learning programme. Women are provided motivation and guidance to complete the courses and also supported after the training, in finding employment. In addition to skills-training, the TWC provides empowerment training programmes such as Gender Sensitivity Training (GST), Work Ethics and Computer Literacy, which are part of the basic competency courses in the Blended Learning Programme.

Sensitivity to connectivity limitations: e-TESDA is accessible to any person using smart phones. Like-wise there are offline downloadable versions of lessons that are available for those with limited connectivity. Supporting software is not available for non-Android mobile units.

Digital literacy trainings that go beyond ‘en-skilling’: Blended learning offers opportunities to make digital literacy more relevant. The students learn how to create their curriculum vitae, write job application letters, and gain access to job sites where they can apply for work online after their certification. They are also made aware of other government online services that they can access in preparation for job application requirements.

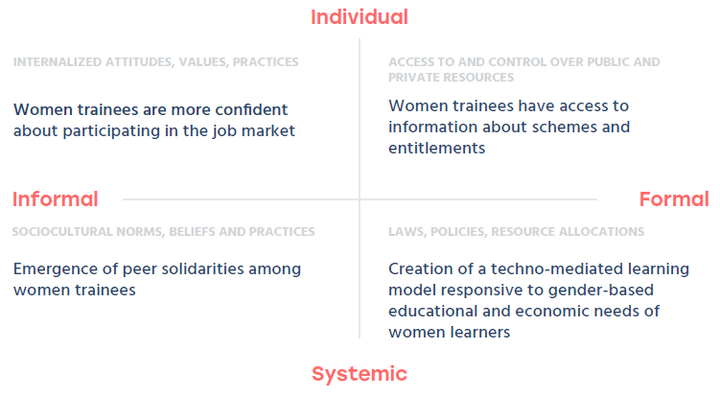

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

The Blended Learning Programme has contributed to improved self-confidence among women learners. Peer interaction and peer support has helped gain in self-esteem. The Gender Sensitivity Training course has been especially helpful in this regard. Women interviewed for this research said that after attending this programme, there has been a shift in the way they think about themselves:

“The TWC blended learning model contributed to widening our knowledge and sharpening our skills… we are confident that we can find jobs right away because when employers find out we got trained in TESDA, they know that we have good training.”

Some students said that through the course they were able to have “personal guidance” and also “interact with other people — their classmates and the public”. The programme has also enabled women to expand their networks of peer support. In fact, a group of female students have put together a social media group to support each other in their training. Women beneficiaries’ awareness of government services, especially those available online, has also increased. For example learners interviewed for this case study shared that now they are aware of other government agencies that offer online services.

Figure 15

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF BLENDED LEARNING PROGRAMME USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

4 Initiatives where Women Are a Large Proportion of Beneficiaries

4.1 SA Community, Australia

Country consultant: Jan McConchie

1. Introduction

SA Community is an online directory in South Australia that provides information to citizens about governmental and non-governmental services, “in the areas of health, welfare, housing, education, community participation, information, legal services, arts and recreation”.19

SA Community was established in response to a request for such a service from an apex body of South Australian community organizations, in the pre-Google days, when the Internet was just taking off and the first directory created was not an online product. A new not-for-profit organization, ‘CISA/SA Connected’, was created for the management of this information directory. Initially, the information that was made available on this directory was that of the community organizations who advocated for the introduction of this service. Over time, with increasing Internet diffusion, the directory went online and the content was expanded through a process of crowd-sourcing. Currently, the SA Community site is also linked to, without being merged with, the official website of the South Australian government www.sa.gov.au. The funding for SA Community is provided by the state government of South Australia.

SA Community is used extensively by older women. Women also constitute a large proportion of the content-contributors, as the voluntary and NGO sector tends to be dominated by women. Further, SA Community is the key information resource used by the Women’s Information Service of the Office for Women, Government of South Australia, that provides face-to-face and phone assistance to women’s informational queries. Similarly, it is also a key knowledge resource that is used in state libraries in South Australia that cater very often to women visitors’ needs.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Creative use of boundary-spanning: SA Community demonstrates how the creative use of new governance arrangements, where the traditional separation between government and civil society is blurred, can help in increasing flexibility and enhance efficiencies of public services. As an information directory managed by an agency that is a not-for-profit organization separate from government, SA Community has a lot of room to cut the red-tape on approvals for adopting unconventional processes, such as ‘crowd-sourcing’ information and posting information about both governmental and non-governmental services, including those offered by community organizations. Similarly, SA Community’s move to opt for informational interlinking with the government’s informational service www.sa.gov.au, without technical integration (such as merging databases or backend architectures), also enables the service to maximize efficiency.

Optimizing user experience even under low-quality connectivity conditions: SA Community seeks to ensure that user experience, even at low internet speeds, is maximized. Therefore care is taken to ensure that content remains unembellished, so that the service can be accessed even under sub-optimal connectivity conditions.

Innovative authentication and verification mechanisms to control quality of content: Verification of the authenticity of crowd-sourced content, without escalating human capital investment to unsustainable levels, is not an easy task. But SA Community has managed to do this by putting in place an entry-level check for non-governmental and community organizations that seek to put up information about their services on the portal. Organizations that want to post information about their services on the portal must provide accreditation information so that their bonafides can be checked in real-time against the database of the relevant accreditation body. In addition to this, the information added by these organizations are vetted by SA Community staff, and there is also a provision for citizen feedback that enables errors and quality concerns raised by citizens to be flagged to the concerned organization that has listed the information, so that appropriate changes are made.

Information architecture: SA Community contributes to enhancing proactive disclosure efforts by providing the right metadata to citizens that enhances the ‘find-ability’ and ‘search-ability’ of information about government and other community services. SA Community is licensed under Creative Commons licensing, so the content on the online directory can be reused as open data. The initiative also adheres to strict data security guidelines, and standard web privacy guarantees.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

Though SA Community is not a women-directed service, its design has contributed to enhanced uptake among women, especially older women. This is because community organizations who contribute to the content are primarily staffed by women, and the users of community libraries also tend to mostly be women. Undeniably, for women, participation in an information and knowledge commons enables greater presence in the public arena, affirming women as producers of, and contributors to, important resources.

Figure 16

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF SA COMMUNITY USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

4.2 Grievance Redress System, Philippines

Country consultant: Maria Juanita Macapagal and Mina Peralta

1. Introduction

The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino20 (PPP) programme is a cash transfer programme with health and education-related conditionalities for the participating households, that is implemented by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), Government of Philippines. Women beneficiaries make up more than 82 per cent of the programme grantees. The programme uses a Grievance Redress System (GRS) as a performance monitoring tool to ensure accountability and transparency in implementation. The programme has a cadre of community leaders (mainly women referred to as Parent Leaders) recruited as mediators between the programme management and beneficiaries to facilitate the grievance redress process and track beneficiary compliance in their neighbourhoods.

The GRS may be considered a basic type of e-government service, but it is an important mechanism for the government to measure the impact of its services on the lives of beneficiaries. The system enables citizens (beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries) to articulate complaints, concerns and preferences with the intention of holding the authorities accountable. The design features include tracking the nature, origin, location and status of complaints pertaining to a number of issues such as household targeting errors, payment irregularities, fraud and corruption. The system complements other MIS modules of the programme, such as beneficiary updation, compliance verification and payments.

The GRS is a way of ensuring the quality of service delivery in the PPP programme. The most common grievance categories identified by the system over two rounds of evaluation, between 2009–2013, are: payment and compliance and exclusion errors. The data received were acted upon, and additionally,the metadata about complaints alerted the programme administrators to make improvements to the compliance monitoring, payment releases and household targeting systems.

In the grievance system, the frontline workers are the City/Municipal Links who record grievances and ensure that it is registered. At the stage of registration in the digitalized GRS, a grievance number that helps future tracking is generated by the system. There are a number of channels through which grievances can be reported, including emails, text messages, Facebook, Twitter, calls to a national hotline, complaint drop boxes, and direct reporting to independent NGO monitoring teams, PPP officials (primarily City/Municipal Links), and Parent Leaders.

Once recorded, the grievance is reviewed, verified and investigated. The Project Management Office of the Grievance Redress Unit is then in charge of reviewing and categorizing each grievance, and referring it to one of the following committees, based on the standardized procedure in place (mainly based on the nature of the complaint):

- A provincial/municipal advisory or grievance committee headed by local chief executives, consisting of representatives from partner agencies and NGOs.

- Regional advisory or grievance committees chaired by the Regional Director of the DSWD, with co-chairs from the Departments of Education and Health.

- National advisory or grievance committees chaired by the Secretary of the DSWD with co-chairs from the Departments of Education and Health.

The grievance is then taken up for fact-finding and resolution, and an official from the municipality or an upper tier of government is placed in charge of this. Based on the report, a decision is taken by the committee to which the grievance has been assigned. Complainants who are not satisfied with the outcome of the process can appeal decisions to the National Grievance Committee, whose decision is final.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Maximizing effectiveness through human and digital processes: The programme uses a hybrid grievance processing mechanism, with a combination of a MIS support architecture and face-to-face intermediation by officials to ensure effective verification, fact-finding, resolution and citizen-feedback.

Consultative approach to grievance resolution: The DSWD refers concerns that emerge through the GRS to partners (the Department of Health, Department of Education, non-government organizations and local government units) that are part of the PPP programme implementation arrangements. Involvement of different departments and stakeholders in data analysis and resolution of complaints contributes to the overall quality of decisions, and thus to accountability and responsiveness.

Clear policy on data: The DSWD has a data security policy. It defines the levels of authority as to who can process and modify transactions. Only the key personnel in the PPP programme are authorized to access the information database. Securing the identity of grievance sources and respect for choice of anonymity is upheld. Reference numbers are generated for all grievances filed and reported, and every grievance is considered. Actions towards resolution of grievances depend on the nature and level of the grievance reported.

Investment in building citizen-trust: Orientations are conducted to familiarize grantees with the GRS. Grantees are also encouraged to approach their City/Municipal Links and Parent Leaders, if they have questions or concerns regarding the programme. Communication strategies cover the promotion of GRS at the village level through Family Development Sessions and orientation sessions with officials of the local government units. Parent Leaders have also motivated their peers (who are beneficiaries) to communicate using their mobile phones (and other online devices e.g. Facebook).

The integration of the GRS in all the activities of the programme benefits users and recipients. For instance, the face to face strategic communication efforts with various groups, such as beneficiaries, partners, NGOs, civil society, and the media, have helped improve public knowledge about the programme and the GRS, especially in a context with connectivity divides. However, field research revealed that more investment in such on-ground awareness-generation activities is required to improve citizen-trust in the programme.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

The Parent Leaders from the local community are often the champions of the GRS. This has contributed to trust-building in the grievance process. The practice of using the metadata about grievances to correct design flaws in the compliance monitoring, payment releases and household targeting systems of the programme’s MIS is worthy of emulation, as a good practice in the area of agile service delivery design.

Figure 17

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF GRIEVANCE REDRESS SYSTEM USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

4.3 Community eCentres, Philippines

Country consultant: Maria Juanita Macapagal and Mina Peralta

1. Introduction

The Philippine Community eCentre (CeC) Programme is a national digital inclusion programme initiated in 2007. It seeks to establish Community eCentres that provide critical ICT, e-government and social services in rural municipalities with minimal or no access to information and government services,21 and where shared Internet facilities are absent. Between 2008–2011, more than 1400 CeCs were set up at the municipality level. A new strategic road-map for 2011–2016 was developed, that set its sight on deeper rural penetration at the barangay (village) level, in partnership with municipal governments.

The Malvar Municipal Government in Batangas province has set up 5 CeCs under this programme: Malvar Main CeC in the town where the Municipality is located; 3 satellite CeCs in the barangays of Poblacion, San Fernando, and San Isidro; and a ‘CeC on Wheels’. The Municipal Planning Officer has been assigned a concurrent appointment as the CeC Manager. This helped the CeC programme gain top level official support in the initial years, when it was still a fairly new initiative in the municipality. The Coordinator for Alternative Learning Systems (a governmental program for providing modularized non-formal education) has been appointed as Assistant CeC Manager. She has enabled linkages between the CeC and the eSkwela/e-school programme of the Bureau of Alternative Learning Systems, which aims at providing ICT-enhanced educational opportunities for the country’s out-of-school youth and adults. The everyday functioning of CeCs is taken care of by a team of knowledge workers, while mobile teachers who are staff of the Bureau of Alternative Learning Systems are in charge of the eSkwela programme.

Though the design of the CeC programme at the national level is gender-neutral, in Malvar, the programme has been able to make inroads in creating empowering cultures of use from which women in the community can benefit. This is because the two ‘champions’ driving the programme in Malvar — the Municipal Planning Officer and the Assistant CeC Manager — have focused on increasing the outreach of the programme to women from various socioeconomic groups in the community: ranging from barangay health workers, daycare teachers, young women in search of alternative education and mothers. The national policy in the Philippines that mandates gender budgeting in all agencies and institutions has helped the municipality of Malvar in bringing in the women’s empowerment agenda into the varied activities of the CeCs. For example, dedicated budgetary allocations for training marginalized women have been made in the municipal budget, which enables the strengthening of the skills-training programme in the CeCs.

Most importantly, site-selection for the establishment of the CeCs has been guided by a gender perspective. For example, the decision to establish CeCs in Barangays Poblacion and San Isidro was taken after these areas were found to have low levels of female work-force participation and a high drop-out rate among young women, through the Community Based Monitoring system instituted by the municipality. For these efforts, the CeCs of Malvar have received national and international recognition.

2. Insights for creating an e-government institutional ecosystem that promotes gender equality

Facilitated public access: The CeC programme has given the citizens of Malvar a place where they can access e-government services through the Internet, on a regular basis. The efforts of the municipal government, through the digital literacy training has been critical to create citizen capabilities for accessing e-government services. The continued provision of Internet access in 3 of the CeCs (Malvar Main CeC, Poblacion CeC, and the CeC on Wheels) has enabled citizens to actually access these e-government services. Knowledge workers play an important role in assisting CeC users, especially in looking up e-government services online.

Partnerships across scale — tapping into local philanthropy and building bridges with national and international programmes: The Municipal Government persuaded a local club, during their 50th anniversary, to donate computers in order to establish the Poblacion CeC. This engagement has resulted in 13 computers and two printers being donated to the Poblacion CeC by the U&I Club since 2013. Additionally, this partnership proved to be beneficial in expanding the reach of the digital literacy training and the eSkwela programme in the municipality. In order to improve and increase the CeC services, partnerships have also been established with the Department of Science and Technology and its offices (the ICT Office and the National Computer Center), the Bureau of Alternative Learning Systems, and Microsoft. Further, the Municipal Government has joined the Philippine Community eCentre Network and Telecentre.org. These affiliations and partnerships add value to local beneficiaries of the programme, while bringing visibility.

Digital literacy and employment oriented applications: Digital literacy trainings are provided free to all citizens regardless of their gender or age. Citizens who want to attend the trainings need to sign up with the knowledge worker. Additionally, the Main CeC and Poblacion CeC have eSkwela installed in their computers and this service is available to learners 15 years old and over. The only requirement for those taking eSkwela is that participants should have completed the free digital literacy training offered at the CeC.

CeCs promoted as a new women-friendly local institution: Meetings of barangay health workers, daycare centre workers, and senior citizens, and announcements after church services, were key offline strategies that were used in the initial years, to enhance the uptake of the digital literacy training. The digital literacy trainings provided to barangay health workers and daycare centre workers (who are mostly women) and the word of mouth publicity generated by these trainees helped the CeCs emerge as women-friendly public access points in their communities. The ‘travelling’ CeC strategy, where the computers are sent to remote barangays for one week, has also proved to be a crucial strategy to build community awareness about the programme.

3. Impacts on women’s empowerment

Trainees in the Malvar CeC programme have learnt how to use the Internet, not just for social media but also for looking up information, communicating through email, and sending online college applications. Women who are undergoing training reported during the study that they have been able to expand their communication horizons and undertake new empowerment journeys, as they now have access to public information they were hithero unaware of.

Digital literacy trainings have enhanced skill-levels and employability of women graduates and their access to the job market. For example, a knowledge worker interviewed for this research shared that one of the trainees in the first batch he taught, applied for a job as a production worker in a factory. She was promoted as line leader because she was computer literate. Another knowledge worker shared that a woman security guard who used to work at the municipality took the trainings, and is now working in Dubai where she uses her knowledge of computers in performing her job as a timekeeper.

Figure 18

ANALYSIS OF EMPOWERMENT OUTCOMES OF COMMUNITY ECENTRES USING GENDER AT WORK FRAMEWORK

4.4 COMMUNITY TELECENTRE INITIATIVE, FIJI

Country consultant: Susanna Kelly

1. Introduction

The Fijian Government Community Telecentre Initiative (‘Telecentres’) is a flagship initiative of Government of Fiji aimed at increasing IT and Internet access for rural, urban and peri-urban communities. The intention behind Telecentres is to facilitate free access to IT services for those who live in remote areas and to cater to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in order to “enable maximum coverage for the Government of the Republic of the Fiji Islands’ online services.” 22 Currently, there are 26 Telecentres nationally. Government statistics show that by April 2015, over 125,000 users have accessed the Telecentres.23 Though the design of the Telecentres is gender-neutral, empirical research for this research revealed that a large number of beneficiaries are women. Hence, this case was selected for its overall significance as a free, public access model in catering to women, a majority of whom have socioeconomic constraints in Internet access.

The programme was started in 2011 under the aegis of the Ministry of Communications. Most Telecentres24 are located in schools. Telecentres are open during school hours and after school between 4.00 pm – 9.00 pm. Access is free and there are Telecentre assistants (‘lab assistants’) to provide technical support.

2. Learnings from the initiative

Widespread connectivity an issue: In serviced areas, Telecentres are significantly increasing access to IT and internet for Fijians who would otherwise have to pay for these services. But despite the policy pledge to increase rural access, telecentre coverage relative to national geography and population is small.

The limitations of a gender-neutral design: The fact that Telecentres are free, located in community facilities, open during the evenings and on weekends, all contribute to the widening of potential access. However, there is no gender mandate to make Telecentres ‘female-friendly’ nor for lab assistants to respond to women service users’ gender specific needs (e.g. low computer literacy). Telecentres seek to promote women’s online participation within the overall policy goal of increasing internet access for underserved communities, but there is no specific attention paid to gender in Telecentre design and delivery. Similarly, women’s rights in the digital space, or protecting these rights are not a visible policy concern.