2.1 BRIDGING THE GENDER DIGITAL DIVIDE: A STARTING POINT

The bulk of literature on ICTs and gender highlights that ICTs are a double-edged sword: while they contain great potential for women’s empowerment, they can also exacerbate existing inequalities. Recognizing the problem of the gender digital divide, the government started its effort to address the gender digital divide from the late 1990s. The Kim Dae-jung administration (1998~2003) referred to by the sobriquet ‘government of the people’ was an advocate of women’s social participation and strategies for gender mainstreaming, and therefore, it actively supported informatization as an issue of women’s human rights.20

Before the establishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality in 2001 as a national women’s machinery, the Ministry of Information and Communication (MOIC) mainly led informatization programmes for women, based on the Framework Act on Informatization Promotion and the Act on Eliminating the Digital Divide.21 The programmes tended to be short-term programmes ranging from one or two day trainings to one to two month programmes.22 Also, the content of the programmes was limited to providing subsidies for ICT training programmes for women and Internet training classes targeting two million house wives in cooperation with Korean Association of Computer Academy. Local government programmes were initiated as a part of Local Informatization Initiatives supported by the central government, and their activities were limited to providing information related to women’s employment, and recruitment and lifestyles; and free computer training courses for women.23

Through a cabinet meeting in June 2000, the government established a Plan on Informatization of Ten Million Citizens that further expanded the programme in scale, with ten government ministries, including the MOIC, taking part in it.24 Around 13.8 million beneficiaries, including housewives, farmers and fishermen and local community members were provided with e-literacy trainings, and 434 thousand housewives were trained from 2000 to June 2002.25 As a result, the number of Internet users increased from 3.1 million in 1998 to 24.38 million (around 56 percent of the total population) by the end of 2001, and the rate of female users increased from 7.7 percent in 1998 to 57.8 percent in 2001.26 However, this initiative had a limitation in that most of the training programmes still remained at very basic levels and were not able to adequately promote professional ICT skills. Table 3 indicates the number of beneficiaries across different target groups, which the Informatization of Ten Million Citizens initiative reached out to.

Recognizing this challenge, the Second Step Training Plan on Informatization of Citizens was announced in 2003, which aimed at training 5 million citizens to become information producers as well as information consumers. It aimed at equipping 3.5 million ‘e-Koreans’ to freely utilize information technologies at work and in their everyday lives, and providing basic trainings for computer and Internet skills for 1.5 million people in vulnerable groups – such as the disabled and the aged. Under the plan, various e-literacy programmes were provided for marginalized groups by the Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity and Promotion. One of the programmes aimed to provide e-Biz trainings to housewives.27

Table 3

Number of Beneficiaries of the Informatization of Ten Million Citizens initiative by Target Group (from 2000 to 2002)

| Target Group | No. of beneficiaries | Target Group | No. of beneficiaries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

The disabled |

101 thousand |

Employees in Private Sector |

1,435 thousand |

|

Farmers |

129 thousand |

Soldiers |

623 thousand |

|

Fishermen |

16 thousand |

Public servants |

510 thousand |

|

The aged |

443 thousand |

Teachers |

1,109 thousand |

|

Housewives |

434 thousand |

Students |

3,373 thousand |

|

Inmates of juvenile reformatory and prisons |

120 thousand |

State-owned enterprise Staffs |

153 thousand |

|

Local community members |

5,359 thousand |

Total |

13,805 thousand |

Source: MOIC internal data cited in KADO(2003), Bridging the Digital Divide White Paper. Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity and Promotion.

2.2 EFFORTS LED BY NATIONAL WOMEN’S MACHINERY

The establishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality (MOGE) in 2001 seems to be a turning point for addressing gender in relation to the informatization and e-government issue. The MOGE has since been renamed the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF). The e-literacy programmes initiated by MOGEF have focused on nurturing female IT professionals since 2002, and have attempted to develop women’s human resources as well as their IT capacities. The training programmes have ranged from basic IT skill courses to advanced IT skills courses including trainings, including on JAVA, web design, IT security, and mobile Java. In addition, there have been some IT training programmes that have aimed at developing specific IT skills tailored to so-called women-friendly jobs such as telemarketing, accounting, fashion-styling, 3D animation, shopping mall merchandising, avatar design, photo shop, etc.28

MOGEF’s IT trainings seem to have been effective in helping women enter into the job market. It has been reported that 52 percent of trained job seekers successfully entered the job market in 2003.29

The MOGEF also established the Basic Plan for Promoting Women’s Informatization (2002~2006) which set out a rather aggressive policy vision on realizing gender equality through women’s informatization, taking one step forward from previous approaches and efforts passively focusing on addressing the gender digital divide.30 Its five focus areas ranged from enhancing women’s access to information and building infrastructure for it; improving women’s information literacy; invigorating informatization in private sector; evaluating and monitoring women’s informatization; and international cooperation.31

Every five years, the MOGEF establishes a Basic Plan on Women’s Policy where national policy directions for women’s empowerment and gender equality are broadly defined. MOGEF’s policy directions on women’s informatization are also in line with the Basic Plan on Women’s Policy. Table 4 below summarizes plans on women’s informatization included in the second, third and fourth Basic Plans on Women’s Policy. The second (2003~2007) and the fourth (2013~2017) Basic Plans on Women’s Policy developed by the MOGEF also included women’s informatization as one of the focus areas for women’s policy for five years.32 The third Basic Plan on Women’s Policy (2008~2012) however did not explicitly set out women’s informatization as a focus area as the Ministry of Information and Communication that had led national informatization efforts was dissolved and jurisdiction on IT-related policies got diffused across various ministries.33 As a result, IT literacy programmes for marginalized groups were greatly scaled down.34 Also, as the Act on Eliminating Digital Divide was abolished in 2009, the informatization programmes for women tended to diminish, except for those targeted at minority women’s groups such as women farmers and international marriage migrant women.35

Table 4

Informatization Issues in Second to Fourth Basic Plans on Women’s Policies

| Plan | Strategic perspective on Women’s Informatization |

|---|---|

|

The 2nd Basic Plan (2003~2007) |

|

|

The 3rd Basic Plan (2007~2012) |

|

|

The 4th Basic Plan (2013~2017) |

|

Source: Korean Womenlink(2014), Women and Media, In Beijing +20 & Post-2015: Changes of Korean Society in Gender Perspectives (November 11. 2014), Korean Women’s Association United and Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, pp. 406-407

2.3 WOMEN-DIRECTED SERVICES

Along with efforts for women’s informatization, the MOGEF has tried to actively use ICTs to better deliver its services. According to a web measurement analysis on MOGEF’s website, it is well integrated into the national Government for Citizen (G4C) web portal with services and content provided via the website.36

Also, there is demonstrated evidence of the impact of online channels on improving the effectiveness of MOGEF’s service delivery.37 Women-net, a platform for online networking among women, is one of the significant e-government efforts of the MOGEF. Its membership amounts to around 5.6 million as of 2014.38 It provides information on policies on women and family, and also directs users to cyber-mentoring and e-learning courses for women’s career development. Through this portal, MOGEF as a women-focused agency of the government of the Republic of Korea, attempts to better communicate with its policy clients; effectively deliver information on its policies to them; and empower women through various online training programmes. Compared to the main webpage of the MOGEF, the Women-net web portal is designed in a more user-friendly way by displaying various menu bars categorized into needs for specific target groups (working women and mothers, women taking a break from their career, women immigrants who are part of multicultural families) and women situated at different stages of their life cycle, even though quantity and quality of the information on each topic vary.39

In line with the recent Government 3.0 initiative, the MOGEF has opened a section for public data release with a menu bar on its homepage (http://www.mogef.go.kr). The section provides a list of public information to be released without request, a platform for requesting information, information on related laws and regulations, budget, etc. The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family has also interlocked its web portal Women-Net along with various SNS platforms. More recently it has attempted to actively utilize smart phone applications for service delivery.

Table 5 outlines the various ICT services that the MOGEF currently provides. The MOGEF has been operating a web portal named Women-net since 2002 (one year after its establishment). The portal was set up in order to effectively provide information and various services for women’s empowerment. In addition to serving as a onestop- shop portal about the Ministry’s services for women, Womennet also has a cyber-mentoring service, which has contributed to women’s empowerment in various ways. Recently, the MOGEF has also attempted to actively explore the mobile opportunity for reaching out to women. Sex Offender Alert Application is one such example. By providing information on sexual criminals, it attempts to protect vulnerable groups (such as women, children) from the threat of sexual crimes.

Table 5

MOGEF’s Services via ICTs (Internet & mobile)

| Webpages | Description |

|---|---|

|

MOGEF Homepage (http://www.mogef.go.kr) |

main homepage of the MOGEF |

|

Women-net portal (http://www.women.go.kr) |

provides one-stop information on women's policies to support various issues according to one's life-cycle and specific needs provides e-learning courses, career coaching, cyber-mentoring for women's empowerment provides government services to find locations of nearby facilities for women such as women's development centres, women's crisis centres, etc. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/women.go.kr |

|

Child-care webpage (https://idolbom.mogef.go.kr) |

provides information on child-care support provided by MOGEF |

|

E-museum for the Victims of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery (http://www.hermuseum.go.kr) |

aims to facilitate accurate history education about the comfort women victims violated by the Imperial Japanese Army delivers historical facts, records and data, victim's oral testimonies, photos, artworks and animation film Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/hermuseum |

|

Webpage on the academy for women in managerial level (http://kwla.kigepe.or.kr/front/main.do) |

provides information on various trainings and leadership programmes for female managers offers online trainings |

|

Webpage on certification of family friendly enterprises (http://ffm.mogef.go.kr) |

introduces various supporting programmes for family friendly enterprises provides information on policies and support programmes for work and family balance |

|

Webpage on support for international marriage immigrants and multicultural family (http://www.liveinkorea.kr/intro.asp) |

provides useful information in various languages for married immigrants and multicultural families |

|

Sex Offender Alert Webpage (http://www.sexoffender.go.kr/index.nsc) |

discloses information on sexual criminals |

| Mobile Applications | |

|

Sex Offender Alert Application |

discloses information on sexual criminals |

|

Work & Family Tap Tap |

provides information on policy supports for women's work and family balance |

|

Danuri |

provides useful information in various languages for married immigrants and multicultural families |

Another good example of women-directed services enabled by ICTs is Safe Return Home Application, led by the Ministry of Security and Public Administration. Utilizing digitalized administrative geographical information, the application helps individuals share details of their geographical location in real time, via texts and SNS services, with family and friend networks. The idea is that such a service can be used as a personal safety measure by individuals, when passing through areas that they consider unsafe.

2.4 WOMEN’S UPTAKE OF E-GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Women’s Internet access and use

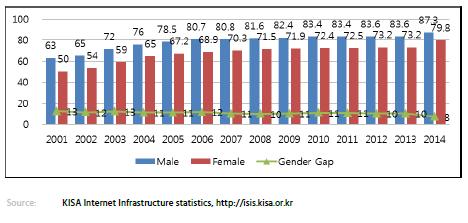

Internet use by both men and women has been increasing for the past years, in Republic of Korea. The gender gap has decreased over the years, and stands at 8%, as of 2014.40 See Figure 1 for details.

FIGURE 1

PERCENTAGE OF MALE AND FEMALE INTERNET USERS

Source: KISA Internet Infrastructure statistics, http://isis.kisa.or.kr

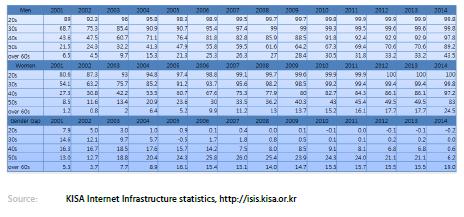

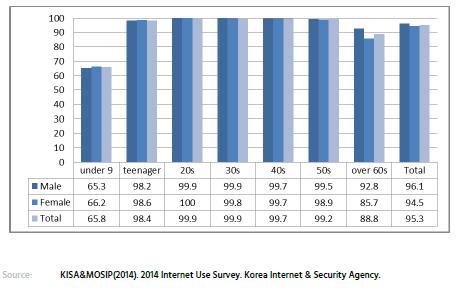

A more detailed examination of the gender gap data for different age groups reveals some differences. As Table 6 and Figure 2 indicates, the gender gap between women and men in their 20’s has reversed now, with women Internet users outnumbering men. For users in their 30’s, the gender gap has systematically reduced over the years and has now evened out. However, among women and men in their 50’s and 60’s, the gender gap continues to persist.

TABLE 6

PERCENTAGE OF MALE AND FEMALE INTERNET USERS BY AGE GROUP

Source: KISA Internet Infrastructure statistics, http://isis.kisa.or.kr

FIGURE 2

GENDER GAP IN INTERNET USE BY AGE GROUP: PERCENTAGE OF MALE USERS MINUS PERCENTAGE OF FEMALE USERS

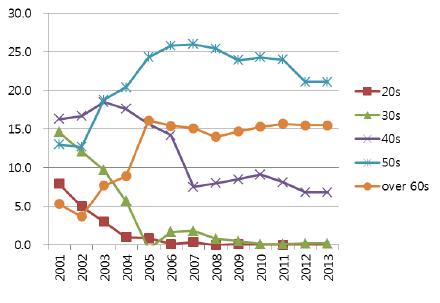

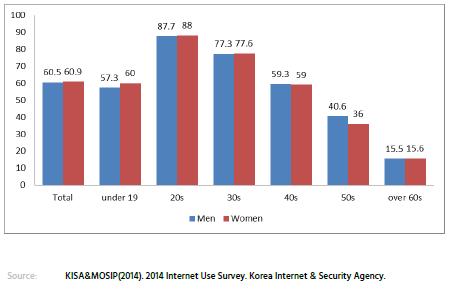

As for SNS (Social Network Services) Use, 60.5 percent of men and 60.9 percent of women are using SNS, and there is little gender gap in SNS use. See Figure 3 below.

FIGURE 3

PERCENTAGE OF WOMEN AND MEN INTERNET USERS

Source: KISA&MOSIP(2014). 2014 Internet Use Survey. Korea Internet & Security Agency.

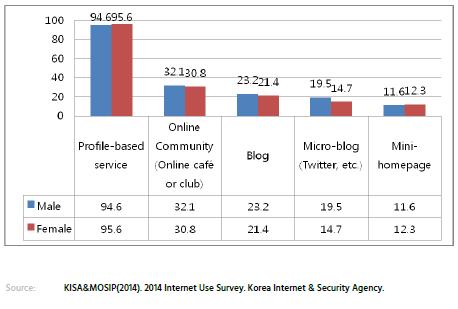

As Figure 4 and Table 7 reveal, the most used SNS are profile-based services for both men and women. There is little gap between men and women’s SNS type-preferences, but across all age groups, men are more likely to use micro-blogs than women. Women tend to utilize SNS for various purposes for multiple purposes, when compared to men.41

FIGURE 4

SNS PREFERENCES OF WOMEN AND MEN USERS (%)

Source: KISA&MOSIP(2014). 2014 Internet Use Survey. Korea Internet & Security Agency.

TABLE 7

SNS Preferences of Women and Men by Age (%)

| Male | Profile-based service23 | Online Community (Online café or club) | Blog24 | Micro-blog (Twitter, etc.)25 | Mini-homepage26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

under 19 |

93.3 |

24.6 |

20.3 |

16 |

13.8 |

|

20s |

96.8 |

36.5 |

29.9 |

26.2 |

15.6 |

|

30s |

96.7 |

33.8 |

24.3 |

21 |

12.8 |

|

40s |

93.1 |

31.9 |

21.8 |

17.5 |

7.8 |

|

50s |

91.7 |

31.1 |

15.2 |

12.1 |

4.7 |

|

over 60s |

82.9 |

30.1 |

11.2 |

9.9 |

3.7 |

|

Female |

Profile-based service |

Online Community (Online café or club) |

Blog |

Micro-blog (Twitter, etc.) |

Mini-homepage |

|

under 19 |

95.1 |

25.5 |

19.3 |

14.9 |

15.3 |

|

20s |

96.3 |

36.8 |

29 |

22.9 |

17.7 |

|

30s |

95.6 |

33.7 |

23.3 |

15.9 |

12.8 |

|

40s |

96.2 |

28.8 |

18.4 |

9.9 |

7.7 |

|

50s |

93.6 |

26.1 |

10.7 |

3.2 |

4.1 |

|

over 60s |

94.2 |

12.5 |

10.4 |

4.7 |

2.1 |

Source: KISA&MOSIP(2014). 2014 Internet Use Survey. Korea Internet & Security Agency.

However, it is pointed out that women’s active use of SNS does not necessarily lead to active participation of women in information production or shaping public opinion. The patterns of SNS use among women and men reflect some key differences: while men are more likely to actively make use of SNS to share opinions, women are more likely to use them as platforms for promoting friendships and familial relationships.46 According to a 2013 survey on the use of, and participation in, social media among women and men, women are less active than men in these spaces. The survey revealed that women’s topics of interest focused on child-care and children’s education. Also, women participated less than men in online discussions commenting on political issues.47

As for mobile phone use, 96.1 percent of men and 94.5 percent of women use mobile phones as indicated in Figure 5. Also, mobile phone access is higher than Internet access and SNS use, among both men and women. Also, across age groups, the gender gap in mobile access is negligible.

FIGURE 5

RATE OF MOBILE PHONE USE AMONG WOMEN AND MEN, DISAGGREGATED BY AGE (%)

Source: KISA&MOSIP(2014). 2014 Internet Use Survey. Korea Internet & Security Agency.

A survey on 4,000 smart phone users also reveals that there is no major gender gap in smart phone use.48 Smart phone access is high among both men (95.4%) and women (94.7%).

To summarize, the RoK government’s programmes for women’s informatization, since the 1990’s, have certainly had a positive impact on women’s access to and use of the Internet. However, improvement in Internet access varies by age. There is little or no gender gap in Internet use among the younger generation. The gender gap persists among the aged whose ICT accessibility is comparatively low. On the other hand, the recent advent of mobile phones opens up new prospects with respect to providing genderequal and generation-equal access.

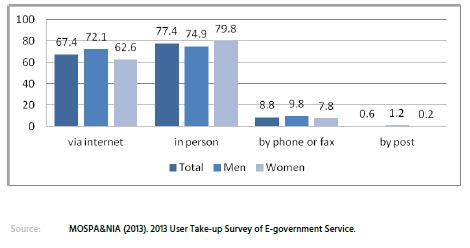

Women’s uptake of online government services

According to the 2013 ‘User Take-up Survey of E-government Service’,49 67.4 per cent of respondents use public services via the Internet, making it the second most common method for accessing public services surpassed only by face to face interactions (77.4%). See Figure 6 for details.

FIGURE 6

MAIN METHODS USED TO ACCESS PUBLIC SERVICES (%)

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013). 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

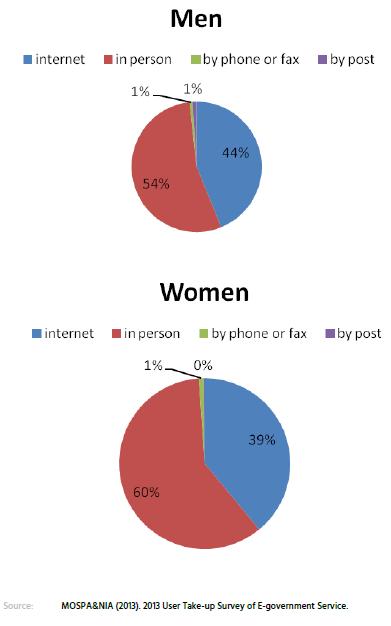

Women’s preference for using online services tends to be lower than men, and also more women prefer going in person when compared to men. However, the difference is marginal. See Figure 7 for details.

FIGURE 7

PREFERRED METHODS TO ACCESS PUBLIC SERVICES

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013). 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

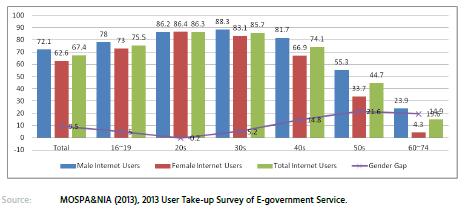

Looking at the rates of public service use via Internet among men and women across age groups, it is clear that the gender gap among younger generations, that is, under 30s, is relatively low. Especially for those in their 20’s, there is little gap between men and women’s uses of public services via the Internet. However, as age increases, the gender gap also goes up, as indicated in Table 8.

TABLE 8

Rates of Public Service Use by Men and Women via Internet by Age

| Age | Total | Men (A) | Women (B) | Gender Gap (A-B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

16~19 |

75.5 |

78 |

73 |

5 |

|

20s |

86.3 |

86.2 |

86.4 |

-0.2 |

|

30s |

85.7 |

88.3 |

83.1 |

5.2 |

|

40s |

74.1 |

81.7 |

66.9 |

14.8 |

|

50s |

44.7 |

55.3 |

33.7 |

21.6 |

|

60~74 |

14.9 |

23.9 |

4.3 |

19.6 |

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013). 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

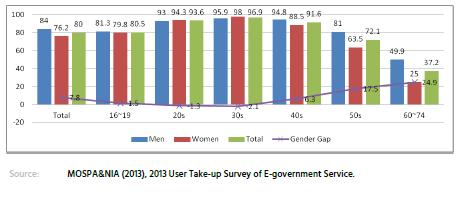

The survey also revealed that the extent of awareness and patterns of use of e-government services differ among women and men.50 76.2 percent of female respondents are aware of e-government services while 84 percent of male respondents are aware of e-government services Figure 8. Similarly, 62.6 percent of female respondents compared to 72.1 percent of male respondents have used e-government services at least once Figure 9. While examining the data for different age groups, we find that there is hardly any gender gap in access to e-government services among those in their 20s and 30s. But as age increases, the gender gap in awareness and use of e-government services also goes up.

FIGURE 8

AWARENESS OF E-GOVERNMENT SERVICES AMONG WOMEN AND MEN SURVEY RESPONDENTS

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013), 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

FIGURE 9

UPTAKE OF E-GOVERNMENT SERVICES AMONG WOMEN AND MEN SURVEY RESPONDENTS

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013), 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

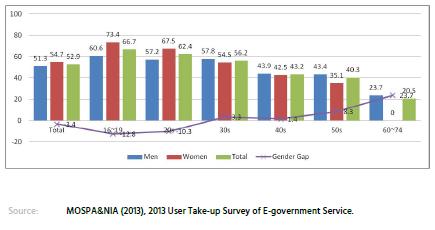

On the other hand, use of mobile e-government services among women and men tells a different story. The rate of women using mobile e-government services (54.7%) is higher than that of men (51.3%). This tendency is pronounced in people in their 20’s. As age increases, the tendency reverses, but the gender gap is not as much as for non-mobile access to e-government, except in the oldest age group (60 to 74 years). See Figure 10 below for details. There is no in-depth research that can provide a clear explanation on why women tend to prefer mobile e-government services, but it can be inferred to be related to connectivity: women tend to have more connectivity via mobile phones than via the fixed broadband, as shown in the previous section on connectivity.

FIGURE 10

UPTAKE RATES OF MOBILE E-GOVERNMENT SERVICES AMONG WOMEN AND MEN

Source: MOSPA&NIA (2013), 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), Women’s Use and Production of Information in the Age of Media Convergence. Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- Jung, 2001 cited in Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit, pp 39-40.

- Jung, Sook-Kyung(2001), Current Projects on Women’s Informatization and Their Problems. Informatization Policy 8(2): 54-72.

- Jung, Sook-Kyung(2001), op.cit.

- KADO(2003), 2003 Bridging Digital Divide White Paper. Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity and Promotion.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- KADO(2003).op.cit

- KADO(2004). 2004 Bridging Digital Divide White Paper. Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity and Promotion.

- Ibid.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit.

- Korean Womenlink (2014), Women and Media, In Beijing +20 & Post-2015: Changes of Korean Society in Gender Perspectives (November 11. 2014), Korean Women’s Association United and Ministry of Gender Equality & Family.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit.

- Choi, Dong-Ju & Hanah Zoo (2011), E-government for Women in Korea: Implications to Developing Countries in Asia Pacific, APWIN 12: 78-111.

- Ibid.

- MOGEF (2014), Internal data source.

- Park, Sung-Jung, Seon-Mee Shin, Mi-Hye Chang, Seung-Ah Hong, Dongsik Kim & Soyoung Kwon (2014), op.cit., pp 16-23.

- KISA Internet Infrastructure statistics, http://isis.kisa.or.kr, and Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit., pp 249-251.

- Social Network Services based on user profile such as Facebook

- Personal journal for an individual that is publicly accessible via web

- A type of blog with comparatively short texts enabling constant comment exchange and updates

- A scaled-down personal webpage for inidividuals

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit., pp 31.

- Lee, Soo-Yeon et al.(2013), op.cit., pp 251-254.

- NIA(2011). Government 3.0. National Information Society Agency, pp 21.

- MOSPA&NIA (2013). 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.

- MOSPA&NIA (2013). 2013 User Take-up Survey of E-government Service.