This section provides an overview on the status of e-government in the country (covering the facets of service delivery, citizen uptake and connectivity architecture) using a gender lens.

2.1 Service Delivery

On the whole, the Bangladeshi government is guided by a gender-neutral vision of ICTs for improving the quality of public service delivery in its e-government efforts. It is this type of thinking that has informed the development of the Bangladesh National Web Portal together with a national forms portal and convergent service delivery platform. The national web portal (www.bangladesh.gov.bd) has been developed in a way wherein citizens can access information and services of all public offices in one platform and web address. Through this single gateway, citizens can access the websites of unions, upazillas (sub-districts), districts, divisions, directorates, departments and ministries. The national web portal contains more than 25,000 government websites, which have information on more than 43,000 government offices. It has uploaded more than 71,000 photographs of the country’s natural beauty, archaeological, historical and traditional sites. Together with the national web portal, the government established Sebakunjo (all services platform) and forms portal. Sebakunjo (www.services.portal. gov.bd) is a web platform where citizens can browse and find all types of public services. The forms portal (www.forms.gov. bd), on the other hand, makes it easy for citizens to search and download government forms. The forms are divided into types - law, job, education, land, agriculture, environment, health, bank, industry, information, post and telecommunication, local government, etc. There are around 1,400 forms; 1,200 are in pdf format. These can be downloaded and filled out. The website (plus the services of the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs) is included in the national web portal.

During an interview for this study, Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and IT, Mustain Billah, demonstrated how the national web portal works, showing all the inquiries made to his office during the day and how all his responses to these inquiries have been logged. In this manner, the government can monitor which offices respond immediately to citizen queries and which offices do not. He explains that this is part of the e-filing system, which has been introduced to provide prompt, transparent and efficient services. The system is in place at the Prime Minister’s Office, 20 ministries, four directorates, 64 deputy commissioner’s offices and seven divisional commission’s offices. To keep the national web portal regularly updated, the government has designated more than 30,000 information providing officers and trained another 71,000 officers. It has around 550 master trainers countrywide and ensures that there is one trainer in every district and upazilla (sub-district).

While inquiries and responses logged under the national web portal by each officer are visible to the monitoring machinery at the government-end of the web portal, on the citizen-end, only the individual citizen who filed the enquiry can access the response. Data about promptness levels of different offices in addressing queries is also not published in the public domain. This makes a citizen-end audit of promptness of different offices in addressing queries quite challenging.

Apart from these initiatives, the government has set up a digital record room particular to matters concerning land. Khatian (land record) services started as a test case through the online system of the Deputy Commission’s Office in Jessore District in 2010. In 2011, it was upgraded to the “Electronic Land Record Service” and piloted in three districts. With its success, the system has been replicated and replaced with the “Digital Record Room”. As of July 2016, 1.95 million records have been digitized and 172,026 online applications have been received.

In the eyes of the government, both men and women are seen as benefiting from such digital innovations. A gender-neutral thinking prevails in the majority of governmental digital initiatives in the areas of service delivery, education, language tools, legal services, media, health, agriculture, business, transport and taxation. Most of these efforts assume a target group that is an homogenous mainstream user and does not take into account the differentiated needs of women.

The government likewise views its ICT initiatives as enforcing its Right to Information Act 2011; knowing fully well that “information is the cardinal source of power - those who possess information are powerful, and those who do not have access to information are powerless” (Mishbah:2013). According to Mishbah, access to information helps increase citizen confidence as decision-making becomes more transparent; assists public administration to become more efficient and effective as record keeping systems are organized and procedures are established; allows scarce resources to be properly applied and utilized; and can serve to increase foreign investment. It is a tool that provides the power to ensure that social services reach the most disadvantaged and marginalized people; supports true social accountability; and promotes political and economic empowerment and the protection of individual rights. As women are one of the most vulnerable and marginalized sectors in society (facing the double burden of generating income and caring for children), the Act provides them with meaningful access to information.

Some e-service delivery projects and programs have yielded benefits specifically for women and can be categorized along the following lines:

- projects with a large proportion of women beneficiaries.

- projects that possess design elements that ensure women’s inclusion.

- projects that are women-directed/exclusively targeted at women.

A. Projects with a large proportion of women beneficiaries.

In 2013, the government established the Teacher’s Portal (www. teachers.gov.bd) with the objective of devising a modern, farreaching supplementary tool for teacher training. Therefore, it designed and developed an online social platform for school and college teachers, which functions as an online repository of multimedia materials and an idea generating/problem solving platform regarding teaching pedagogy. In other words, the portal provides a peer-to-peer collaborative environment for lifelong learning support for teachers.

a2i Program Policy Advisor Anir Chowdhury, in a presentation to United Kingdom Trade and Investment (UKTI) on 30 January 2015, said that the Teacher’s Portal is the most cost-effective way to conduct teacher training7. The country has more than 30 million students and nearly one million teachers in over 120,000 primary and secondary schools. Traditional face-to-face training entails so much resources that it takes five to six years to update the knowledge and skills of all teachers in the system. For this reason, the government has no option but to devise alternatives to traditional pedagogic training.

As of July 2016, more than 132,000 teachers from all over the country have registered in the portal, of whom 45.85 per cent are female. They can access around 100,000 pieces of content developed and uploaded by their fellow teachers relating to the teaching of languages, information technology, science, social studies, religious studies, mathematics and others. The a2i program also established 23,331 multimedia classrooms (i.e., one laptop with Internet connectivity and a projector) in schools so that teachers can access the portal and utilize the said technology as part of their teaching-learning methods. It must be noted here that over 39 per cent of the country’s teachers are female, and hence the portal is an important initiative to assess, in the study of the gendered impacts of e-service delivery. In a survey undertaken amongst registered portal users, the a2i program discovered that the portal furthered gender equality as it reduced discrimination against female teachers. Table 1 illustrates the benefits that female teachers are perceived to obtain from the said portal.

Table 1

Perceived Benefits to Female Teachers of the Teacher’s Portal

| Perceived Benefits | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Won't need to travel far | 80.7 |

| Can receive training besides doing housework | 80.7 |

| No security concerns | 33.1 |

| TCV (Time, Cost and Visit) decrease | 29.5 |

| More active participation | 23.5 |

| Teacher skill development | 22.9 |

| Religious restriction is not a barrier | 11.4 |

| Gender gap in teacher-related knowledge would decrease | 6.0 |

| No need to spend night somewhere else | 5.4 |

| Pregnant teachers won't miss training | 4.2 |

| Teachers uncomfortable at big forums can take training at their own convenience | 3.0 |

| Disabled teachers can also receive training | 0.6 |

| Others | 3.6 |

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3_bn2w31Cs

As illustrated by the table, the respondents indicated that females benefit from the portal since they do not have to travel far (80.7 per cent), can receive training while doing housework (80.7 per cent), and do not have security concerns (33.1 per cent). It should be noted that in Bangladesh, women have less mobility as compared to men due to reasons such as security, household chores and norms binding women to the home. Given this, many female teachers miss training opportunities, particularly if they need to travel to the regional or national capital. With the portal, female teachers need not worry about leaving their homes for training and for this reason, many of them registered to be members.

B. Projects whose design elements ensure women’s inclusion.

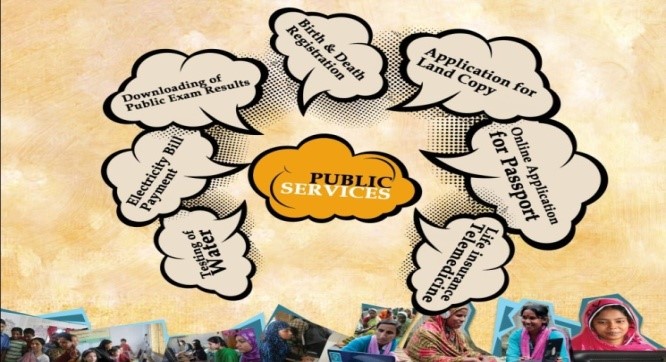

Gender-responsive design is exemplified by the a2i program’s flagship project, the Union Digital Centers (UDCs). The UDCs serves as an alternative to government front-offices for service provisioning. In the past, people needed to travel long distances to reach government offices located in urban and/or semi-urban areas. They thus had to spend a lot of time traveling back and forth; especially because of the lack of information regarding the processes and requirements to obtain public documents. They also had to incur additional costs such as transportation, accommodation and food. UDCs decentralize the delivery of public services; bringing both public and private services to millions of underserved citizens. Asad-Uz-Zaman (2012) provides a list of public and private services offered by these digital centers. Public services include downloading of public exam results, application for land copy, online application for passport, electricity bill payment, birth and death registration, testing of water, life insurance, telemedicine, etc. Private services include email, Internet browsing, ICT training, mobile banking, photo ID, scanning, photocopying, knowledge services, online job applications, etc. UDCs provide a total of 102 public and private services. A snapshot is shown in Figure 1.

Nine years after declaring Digital Bangladesh, the government has established UDCs in all 4,547 union parishads (lowest level government service offices) of the country. The government, however, adopted a business model in operating the UDCs, bringing in local entrepreneurs to run the centers and entering into numerous agreements with corporate entities. Instead of going at it alone, the government sought market relevance and sensitivity to citizens’ demand. With entrepreneurs, the UDCs would not be shutting down on weekends like government offices normally do. As a result, UDCs are believed to be citizencentric and bottom-up in approach. They function as one-stop information and service delivery outlets.

Figure 1

Public and Private Services Offered in Union Digital Centers (UDCs)

According to Naimuzzaman Mukta, People’s Perspective Specialist, a2i (Access to Information) Programme, the UDCs’ design elements are very novel since it reaches out to the underserved, extending the service beyond usual office hours. A typical center is about four kilometers away from a person’s home. A government sub-district office is about 20 kilometers away whereas a district office is more than 30 kilometers away. The UDC management model fuses together the mandate and infrastructure of the public sector and the entrepreneurial zeal and efficiency of the private sector. It also requires a male and a female entrepreneur for each UDC. In doing so, it ensures women’s empowerment as women have the opportunity to become entrepreneurs and women citizens can be attended to by a person of the same sex, which is highly beneficial given that UDCs are seen as public spaces (and for those communities with conservative values, women are barred from entering such spaces occupied only by men).

As of July 2016, UDCs have provided 237 million services, undertaken 75 million birth registrations, processed the registration of 2 million prospective migrant workers, included more than 4 million citizens in m-banking and covered 0.29 million citizens for life insurance. The entrepreneurs, who laboured for such achievements, earned USD 28.15 million. With the policy of making women co-managers, UDCs have become more accessible to women and have made possible womenspecific livelihood projects (which were done in partnership with corporations).

The a2i program has identified three challenges that are being faced by the UDCs, at present. First, the entrepreneurs need to find the right mix between financial and social sustainability. Citizens now trust UDCs as a decentralized government desk, as indicated by their popularity. However, the financial viability of UDCs remains a problem in many areas. Second, the quality of service differs from one UDC to the other. The a2i program admits that they have not ascertained or studied these differences in quality. Third, many female entrepreneurs simply allow their male counterpart to take the lead. Some have also stopped going to UDCs after getting married or after giving birth. As a result, the design for women’s participation in UDCs has not effectively materialized. Given that UDCs are considered as public spaces, the absence of female entrepreneurs makes it harder for women users to enter the centers given social barriers and norms in relatively conservative communities.

C. Projects that are exclusively directed at women

In accordance with its gender strategy, the a2i program has embarked on several projects to empower women, which it does in collaboration with the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs and/or Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and IT. For example, it gives out Leadership Awards to women role models as part of celebrating International Women’s Day. As part of the information portal/ content repository “Jatiyo e-tathyakosh (http://www.infokosh.gov.bd/)”, a section containing content on women’s health and violence against women has been developed. The portal was established in 2011 with contributions from various organizations on topics such as health, education, agriculture, law and human rights, non-farm activities, disaster management, employment and commerce. It has, at present, 90,000 pages of content.

In March 2013, it opened the “Service Innovation Fund” to provide seed funds and incubate cost-effective, citizen-centered design innovations to improve public services for underserved communities. To date, the program has allocated one-third of its funds to support 13 women-oriented projects, incubated jointly by government, NGOs and the private sector. One of the more successful projects is called Joyeeta (or victorious in English; ejoyeeta.com) which enables more than 60,000 women producers and 5,000 micro-entrepreneurs to advertise and sell their products online. E-Joyeeta was set up as part of the a2i program service innovation fund with the involvement of the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, Union Digital Centres, private sector organisations and NGOs.

According to Deputy Secretary and Additional Director of the Women Affairs Department, Shahnowas Dilruba Khan, ejoyeeta. com e-business platform aims at supporting and facilitating grassroots women entrepreneurs showcase their arts, crafts, products and services. The products sold cater to men, women and children. There are also home decorative items. Consumers can easily log into the website and create their own account. If they wish to purchase products, they can either pay through a bank (Dutch Bangla Bank),the mobile financial service provider (bKash) and/or cash on delivery. The money goes into the bank accounts of the women entrepreneurs. The delivery can be made within 24 hours. In addition to the website, the Joyeeta project has established an independent sales center called Joyeeta Marketing Center at the fifth floor Rapa Plaza, Dhaka City. There are around 140 stalls in the center. Consumers can go here and purchase their desired goods. In interviews conducted for this research, the stall owners expressed confidence about the prospects of the Joyeeta project. They regularly brand their products through the online platform. As a result, the sales of their products increase, especially during cultural and religious festivals. With a steady income source, the project has helped them improve their quality of life.

The latest e-government innovation exclusive to women is the “Joy” mobile app, launched in August 2016, as part of the a2i programme in partnership with the Ministry for Women. The mobile app aims to provide instant support to women or children falling victim to any type of violence. When the emergency button is pressed in the app, a message is sent over to the national helpline center, police control room, nearest police station and friends or family members. The a2i program instructs that “any woman or child facing unfavorable or violent situations can quickly send a text message to 10921 via this app” to get help immediately. In case the user is not able to access the app in an emergency, the mobile’s power button has to be pressed four times which will put the cellphone on vibrate mode, and with the fifth press of the power button, the message will be sent to the respective authorities for help. A few reserved numbers can be set up along with the phone number of authorities that are already in the app, once they are contacted, they track the user based on GPS location to provide instantaneous support. Mobile operators have been asked to allow the use of the ‘Joy’ app free of charge. The app is on a trial run in a few cities such as Jessore, Keraniganj and Tongi. However, in order to analyse the effectiveness of the app, dedicated studies are needed.

2.2 Citizen Uptake

With an enabling environment, Bangladeshi citizens have embraced the digital age; participating and benefiting from various e-government initiatives. The Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) shows an increasing trend in Internet use in the country. From only 0.07 per cent in 2000, it rose to 14.40 per cent in 2015. The astronomical increase was due to mobile Internet usage estimates. In 2013, BTRC estimated that the population of Facebook users in Bangladesh is 3.39 million.

Table 2

Percentage of Internet Users in Bangladesh (2000-2015)

| Year | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 131,280,739 | 0.07 |

| 2005 | 142,929,979 | 0.24 |

| 2010 | 151,616,777 | 3.70 |

| 2015 | 160,995,642 | 14.408 |

Source: Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission, 2016

With greater Internet access and use, more citizens participated in e-government initiatives. As of July 2016, the a2i program reported more than 90 million hits per month for the National Web Portal, which contains 25,000 plus government websites. The type of content visited may be broken down as follows:

Table 3

Type of Content Visited in National Web Portal (average per month)

| Portal Type Visited | Number of Hits |

|---|---|

| e-Directory Users | 7.65 million |

| e-Services Users | 1 million |

| Government Forms Users | 0.25 million |

| Hotels and Rest Houses | 1,728 |

| Tourist Users | 1.5 million |

| Growth Centers/Markets | 10,944 |

| Religious Institutions | 19,897 |

| Public Representatives | 26,000 |

| Photographs of Important Places | 71,000 |

| Educational Institutions | 65,000 |

| Development Projects | 65,538 |

| Financial Institutions | 1,386 |

Source: a2i Program, Prime Minister’s Office

There were a total number of active UDCs registered in July 2016. On the Teacher’s Portal, there are 132,300 members; 120,000 teachers have been trained on operating multimedia classrooms; and there are 39,000 blog posts; 98,375 active users monthly; and nearly two million page views monthly. However, genderdisaggregated data of the uptake of the Teachers’ Portal is not available.

Truly, Bangladesh may no longer be categorized as a country with deficient e-government capacity where e-government is low priority. Its e-government has come a long way since the 2001 UNDPEPA and ASPA study. The country has moved up significantly in the e-Government Development Index from a world ranking of 150 in 2010 to 124 in 2016.

Table 4

e-Government Development Index and World Ranking for Bangladesh

| Year | e-Government Development Index | World Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 0.3028 | 150 |

| 2012 | 0.2991 | 134 |

| 2014 | 0.2757 | 148 |

| 2016 | 0.3800 | 124 |

Source: UN e-Government Knowledge Database (2016)

Bangladesh’ Telecommunication Infrastructure Index and Human Capital Index have shown improvement. According to the UN data, around 9.6 per cent of the population uses Internet9. There are 75.92 mobile telephone subscriptions per 100 inhabitants. Literacy rate has reached 61.55 per cent and gross enrolment ratio is 39.59 per cent. It should also be noted that the country has a world rank of 84 in the e-Participation Index. The UN believes that promoting participation of the citizenry is the cornerstone of socially inclusive governance. The e-participation index (EPI) focuses on the use of online services to facilitate the provision of information by governments to citizens (“e-information sharing”), interaction with stakeholders (“e-consultation”), and engagement in decision-making processes (“e-decision making”). The initiatives of the a2i program towards e-participation have improved the country’s world ranking and since these are still in the early stages, e-participation is expected to grow further in the coming years.

Table 5

Telecom Penetration and e-Government Development Components for Bangladesh (2016)

| Indicators | Figure |

|---|---|

|

e-Government Development Index

|

|

|

Online Service Index

|

|

|

Telecommunication Infrastructure Index

|

|

|

Human Capital Index

|

|

|

e-Participation Index

|

|

Source: UN e-Government Knowledge Database (2016)

For these reasons, it is hardly surprising that in 2016, for the third consecutive year, Bangladesh won the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) Award for initiatives under the a2i program. The innovations include Service Process Simplification (SPS) for Increased Transparency, Efficiency and Responsiveness (category 6: enabling environment), Development of the webbased Environmental Clearance Certificate (ECC) Application System of the Department of Environment (category 7: e-government), Teachers’ Portal for Empowerment (category 9: e-learning), and Farmer’s Window (category 13: e-agriculture).

Digital Divide in Bangladesh

Although citizen uptake of the Internet and e-government services has been expanding drastically, there exists a digital divide in the country.

It is important to examine the concept of the digital divide before discussing its specific manifestations in Bangladesh. Manicinelli (2007) explains that there are three types of digital divides: (1) access divide (those with and without access to ICT), (2) usage divide (those who use and do not use ICT), and (3) quality of use divide (difference in usage by users). To measure the digital divide, the Digital Divide Index (DDIX) may be utilized. Husing and Selhofer (2002), after measuring social inequalities in European ICT adoption, concluded that the following groups are at high risk of being impacted by the digital divide, along various socio-structural axes: gender (women), age (50 years and older), education (low education group) and income (low income group). The DDIX indicators consider the percentage of total computer users, percentage of computer users at home, percentage of total Internet users and percentage of Internet users at home. A low score in the DDIX may indicate a lower quality of life. Manicinelli (2007) asserts that the lack of access to digital technologies puts individuals at a disadvantage. They are excluded from benefits of changing social structures and relationships, new working methods, new ways of education and training, and emerging communities of learners in the digital society.

In Bangladesh, those with lower education, those residing in rural areas and those who are female are at a higher risk of being unconnected, reflecting global patterns in digital divides. Table 6 shows that those who are pursuing/have completed bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and/or medical/engineering degree account for 58.32 per cent of the country’s Internet users. Those who are pursuing/have completed technical/vocational education comprise 8.0 per cent while those who are pursuing/ have completed lower and higher secondary education make up 9.6 per cent. In other words, the more educated one is, the more likely one is to have access to the Internet.

Table 6

Individuals Using Internet by Gender and Education

| Aspects | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No education | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Class I to V | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Class VI to VIII | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.48 |

| Class IX to X | 4.25 | 2.95 | 3.6 |

| Lower Secondary | 4.27 | 2.83 | 3.65 |

| Higher Secondary | 6.74 | 4.62 | 5.95 |

| Technical/Vocational | 8.05 | 7.84 | 8.0 |

| Bachelor's Degree | 13.47 | 12.59 | 13.21 |

| Master's Degree | 18.19 | 16.57 | 17.76 |

| Engineering/Medical | 27.2 | 27.96 | 27.35 |

Source: The Bangladesh Literacy Survey, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), 2010

Table 7, meanwhile, indicates the divide between urban-rural and the male-female users. In 2013, only 6.6 per cent of the Bangladeshi population used the Internet. There were more urban dwellers (18.1 per cent) using the Internet as compared to rural residents (2.1 per cent). In addition, more men (8.2 per cent) were using the Internet as compared to women (5.1 per cent). In both urban and rural areas, there was a greater percentage of male users as compared to female users.

Table 7

Individuals Using Internet by Gender and Location (2013)

| Aspects | Percentage |

|---|---|

| All Individuals | 6.6 |

|

8.2 |

|

5.1 |

| All Urban Individuals | 18.1 |

|

21.8 |

|

14.6 |

| All Rural Individuals | 2.1 |

|

2.9 |

|

1.3 |

Source: ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicator Database

The following sections discuss the digital divide between men and women in the country. First, it looks at the case of affluent urban women and second, it investigates the digital exclusion of rural women.

The Case of Affluent Urban Women. Although there exists a digital divide between men and women in the country, the degree of inclusion/exclusion is not determined by gender alone. Genilo and Akther (2015) argue that the digital inclusion/ exclusion of women is determined by both the individual’s sociodemographic context (age, education, location, occupation and civil status) and the citizenship status of her local community in ethnic, religious and ideological terms. In this sense, it cannot be said the women per se are digitally excluded. With the right demographic and socio-economic characteristic, women have been shown to be digitally included. Several studies (Haque, 2013, Hossain & Sultana, 2014 and Haque & Bin Qader, 2014) have documented that urban, affluent and educated women who belong to liberal (secular) minded families are very much integrated into the digital world.

The divides in terms of women’s access to STEM careers, however, stubbornly persist. The Managing Director of PlusOne, a cloudbased telemedicine platform, in an interview with the Dhaka Tribune on 27 April 2017, said that the man-woman ratio in the ICT sector is still “unacceptable”. She felt that more women need to be enrolled in ICT courses; more women need to be recruited to fill in jobs in the sector; and strong mentorship should be provided to women so that they believe that can compete equally against men. At the moment, it is only the affluent women who have made some gains in penetrating the ICT sector. Genilo, Akther and Haque (2013), after in-depth interviews with 12 women students, professionals and entrepreneurs who have succeeded in the ICT sector, discovered that women who were successful had the following personal characteristics, they: expressed an inclination towards computers and technology; were exposed to computer education and Internet at an early age; owned a laptop, desktop or tablet and had Internet connection at home or in school; managed to navigate the Internet in English and in Bangla; possessed computer skills (high computer literacy); used computer and the Internet for a variety of purposes (relatively superior quality of ICT usage); and had social support for ICT use. These women belonged to families with liberal (secular) mindsets.

Digital Exclusion of Marginalized Rural Women. The scenario for women residing in rural areas, on the other hand, was very different. Unlike their urban counterparts, many women do not own or possess desktop and laptop computers or mobile phones with Internet access. Rather, most can only access the Internet from the Union Digital Centres (UDCs) and/or if their male relatives are willing to lend them their computers. Genilo and Akther (2015) visited two UDCs located in two differing types of villages - one with a more secular ideology (Kapasia, Gazipur, Dhaka Division) and one with a more Islamist belief (Sharsha, Jessore, Khulna Division). During the visit, around 30 male and female UDC users, UDC entrepreneurs and community leaders were interviewed in-depth. From the interviews, they constructed four levels of digital inclusion/exclusion of male and female respondents.

Matrix 1

Levels of Digital Inclusion/Exclusion of Male and Female Respondents

| Tier | Gender and Occupational Groups | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. (Most Included) | Males: Students, Professionals and Businessmen |

|

| 2. (Relatively Included) | Females: Students in both villages |

|

| 3. (Relatively Excluded) | Females: Professionals in both villages and Housewives in Kapasia |

|

| 4. (Most Excluded) | Females: Housewives in Sharsha |

|

Source: Genilo and Akther (2015)

At the highest level of digital inclusion (most included), one finds male respondents – students, professionals and businessmen. They have complete freedom to access the Internet and own ICT devices. At the second level (relatively included), are female students. They are allowed to visit the UDCs and use their male relatives' gadgets, mainly for educational purposes. Also, they have relatively higher language skills and computer literacy. Basically, rural women’s access to digital devices depends on the support of men. The male family member buys the SIM card and the mobile phones. Female members may use mobile phones but they are not the real owners. They need to seek permission from their husbands. At the third level (relatively excluded), one spots female professionals and housewives in the secular-minded village. They are allowed a few visits to the UDCs. They have moderate computer and English language proficiency. Since many Kapasia housewives have husbands working abroad, they need to access the Internet for various reasons. At the lowest level (most excluded), one finds the housewives in Sharsha - who rarely visit the UDCs. They are also digitally excluded due to weak English language skills and also, they are not really interested in knowing about digital technologies.

Matrix 2

Description of Individual Characteristics affecting Women’s Digital Inclusion in the Select Villages

| Characteristics | Description |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Students have a high level of digital inclusion in both communities. This is because it is socially accepted that students? main responsibility is learning and computers are part and parcel of the learning process. Professionals likewise have a moderate level of digital inclusion given their need to search for jobs, communicate with colleagues and look for work-related information. |

| Civil Status | Once married, the key responsibility of women is to look after the home and their children. The enormity of the responsibility affects their mobility (like going to the telecenter). |

| Presence/ Absence of husbands | When husbands are working abroad, housewives need to fill in their shoes in terms of becoming the head and main decision maker of the household. They need to be mobile and also search for information in order to make better decisions. Thus, housewives whose husbands are away tend to access the Internet more, when compared to their counterparts whose husbands are still residing with them. |

Source: Genilo and Akther (2015)

Based on these, Genilo and Akther (2015) conclude that certain individual variables affect women's digital inclusion/exclusion in Digital Bangladesh - occupation, civil status, education and presence of the husband. Moreover, community ideology also affects women's digital inclusion/exclusion. Relatively secular-minded villages are more inclusive as wives participate in decision making and are able to pursue professions as long as they fulfil household work. They can also join community activities. In more conservative communities and villages, women are discouraged from pursuing higher education and professional careers. They are mainly tied to the home; taking care of their husband and children. The roles imposed on them have a bearing on their access to UDCs.

Matrix 3

Description of Community Citizenship Characteristics affecting Women’s Digital Inclusion in the Select Villages

| Characteristics | Description |

|---|---|

| Secular (Kapasia) | Women are mainly responsible for the children and home but can make decisions on certain matters such as education, health and family planning. They are allowed to pursue higher education and embark on a professional career as long as they fulfil their household duties. They are not prohibited from joining social clubs and organizing social events. Women with good qualifications are encouraged to hold political positions. The participatory role of women in household, community and politics warrants their access and use of ICTs. |

| Islamist (Sharsha) | Women are mainly responsible for the children and home. They cannot make decisions without the consent of their husbands but are allowed to voice their opinions. They are not encouraged to pursue higher studies or embark on professional careers. Rather, they are persuaded to marry early. They can participate in religious projects and foundations but dispirited to organize community events. Some are prevented from voting and engaging in political activities. As a norm, married women should not freely mix with men in public spaces. The passive role of women and restrictive cultural norms become hurdles in accessing and using ICTs. |

Source: Genilo and Akther (2015)

2.3 Connectivity Structure

Bangladesh has great digital ambitions. It wants to become the next ICT hub after Silicon Valley, Seoul, Boston and Bangalore. It plans to earn USD 5 billion annually from the ICT industry and create one million jobs by 2021. To enable this, the government knows that it needs to drastically improve its connectivity structure. For this reason, the government entered into an agreement for a second submarine cable. A consortium of 15 telecommunication operators from 16 countries across three continents built the South-East Asia-Middle East-Western Europe 5 (SEA-ME-WE-5). The 20,000 kilometer cable from Marseille to Singapore would be offering 100gbps DWDM technology; having a capacity of 24Tbps on three fibre pairs. This would deal with the quadrupling of bandwidth demand between Europe and Asia. Bangladesh was connected to the second submarine cable via Kuakata landing station on 21 February 2017. Through this, the country is expected to get another 1500 Gbps bandwidth. Currently, it has nearly 300 Gbps bandwidth from the first submarine cable. At the time of writing this paper, the connection between Kuakata landing station and the mainland is yet to be established.

True enough, the demand for Internet connectivity has been expanding in the country and the second submarine cable comes at a very opportune time. The BTRC in July 2016 reported 63.91 million mobile Internet subscribers. In many respects, Bangladesh has come a long way since it awarded a license to its first telecommunication operator in 1989. UK-based Consulting Company Deloitte (2015) stated that “the increase in mobile access has brought a wide range of benefits to the Bangladeshi economy and society, including increased productivity and economic growth.” It likewise reported that over 90 per cent of people with access to the Internet use it via mobile connection over the 2G network, via feature-phones or low-end smartphones. Only 4.5 per cent of the population is connected to a 3G network. Given that fixed line penetration is less than one per cent, mobile phones could be the most cost-effective way to extend access to ICT and broadband Internet in the country.

The Next ICT Hub

Bangladesh appears all set to become the next ICT hub. In recent years, it has attracted global ICT companies such as Samsung and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) – which have established their Research and Development (R&D) centers. Gartner, a technology research house, has included the country in the top 30 outsourcing destinations in a 2010 report (Mashroor, 2013). According to the Bangladesh Association for Software and Information Services (BASIS), the software market in the country has grown more than 50 per cent in the last two fiscal years. The export of software products may even exceed USD 100 million next year (Huda, 2013).

There are more than 150 registered companies in Bangladesh that export software products, mainly mobile application solutions and IT-enabled services (ITES). Moreover, there are an estimated 75 freelance software developers. Tandon (2006) had estimated the ICT industry in the country to be growing at an average of 20 per cent per annum for the previous seven years.

Apparently, the country is experiencing a third wave of IT outsourcing. The first wave was in consumer electronics while the second wave was in auto components, pharmaceutical and telecom equipment. The third wave of outsourcing consists of call centers, payroll processing, data entry, software engineering and research and development. BASIS has projected a tripling of current export performance in the near future if sufficient telecommunication infrastructure is provided. For BASIS, Bangladesh has comparative advantages to take a bigger slice of the global IT/ITES market. The country has abundant young and trainable labor, low IT/ITES labor costs, supportive government for digital initiatives and an active industry association.

In the eyes of the government of Bangladesh, ICT development is an engine for economic growth, particularly in the manufacturing and service industries (Tandon, 2006). In order to pursue its plans to establish high tech zones and a software technology park with dedicated data communication facilities, it set up in 2010 the Bangladesh hi-tech Park Authority (BHTPA) - an autonomous body to develop the ICT industry through the creation, management operation and development of hi-tech parks. In the parks, foreign investors are granted special privileges such as allowing 100 per cent foreign direct investment, provisioning of a single window agency, granting 10-year tax exemptions, building separate power plants, enabling duty-free import of capital machinery, providing fibre optic connectivity and ensuring direct rail connectivity. In line with the government’s vision to develop Digital Bangladesh, a total of twelve parks will be established in separate districts - Jamalpur, Natore, Thakurgaon, Comilla, Maymensing, Kareniganj (Dhaka), Barisal, Rangpur, Rajshahi, Sylhet, Khulna and Chittagong.

Women’ participation in the ICT Sector. As a result of these developments, there is a growing demand for ICT workers in the country. According to Tandon (2006), the types of ICT jobs for which skilled labour is in desperate need in the country include ICT programming and applications, ICT platforms to support enterprises and ICT manufacture, service and repair.

In top leading newspapers, such as Prothom Alo (First Light) and Daily Star, there has been a shift in the types of ICT job vacancies and qualifications between 2004 and 2013. From being more technical/engineering oriented, jobs have shifted to ICT outsourcing such as data entry, call centers, etc. Keeping in line with this shift, the educational qualifications in demand have moved from technical/computer/engineering degrees to more general and diploma degrees. In both time periods, there is a demand for teachers for private and public universities offering computer, engineering and technical degrees. One major cause for concern regarding the fulfilment of this ICT hub aspiration relates to the country’s work force. Tandon (2006) estimated that “the labour force is growing at almost twice the rate of the population growth, and this relationship is likely to remain unchanged for the next two decades or more as a direct result of the changing demographic dynamics.” Furthermore, the deceleration of population growth could be offset by increased participation rates of women.

To increase women participation in the ICT sector, Tandon (2006) explained that the government needs to implement “effective, pro-active and deliberate policies that push for the social inclusion of women in all spheres of economic and social activity and decision-making.” In addition, in a 27 April 2017 interview with Dhaka Tribune, Farhana Rahman, Vice President of Bangladesh Association of Software Information and Services stated that the flexibility in ICT jobs suit women. She noted that women traditionally have more responsibilities at home and people working in IT can have that flexibility if needed. “Women who want to give more time to their families, women who want to be entrepreneurs - should come into the IT industry. It has a huge potential.”

It is also important to recognize that there is also a rural-urban divide when it comes to women’s participation in the ICT sector. Currently, there is very little scope for rural girls to study ICT. Schools in major cities provide proper computer labs to facilitate ICT training. Moreover, urban families usually have a computer at home. For students in rural areas, the situation is completely different. Very few rural schools and colleges across the country have fully-fledged computer labs and trained teaching staff. The Barisal Teachers Association President Ashish Kumar Dashgupta informed Dhaka Tribune on 27 April 2017 that although ICT is a compulsory subject for all students, there are simply not enough teachers for the subject. Table 8 illustrates the state of ICT infrastructure in primary and secondary schools across the country.

Table 8

ICT Infrastructure in Primary and Secondary Schools

| Aspects | Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 55% | 71% |

| Telephone Facility | 0% | 93% |

| Computer Laboratories | 1% | 38% |

| Internet Access | 3% | 22% |

| With Website | 0% | 1% |

Source: UNESCO, Institute of Statistics, 2014

As can be gleaned from the table, secondary schools have better ICT infrastructure as compared to primary schools. They have more computer laboratories and have greater Internet access. They also have more connection to electricity and have telephone facilities. However, it should be noted that schools in urban areas have better ICT infrastructure as compared to their rural counterparts. The government would need to exert more effort in this area if its ICT hub ambition has to work out.

Another track where government efforts are required to increase women’s participation in the ICT sector is that of skill development initiatives. Both Shahnowas Dilruba Khan (Deputy Secretary and Additional Director, Department of Women Affairs, Ministry of Women and Children Affairs) and Mustain Billah (Deputy Secretary, ICT Department, ICT Division, Ministry of Posts, Telecommunication and IT), in separate interviews, revealed that several projects have been undertaken to bring women into mainstream development by initiating them in the ICT sector where they can get new job opportunities. The a2i program, for example, partnered with Bangladesh Women in Technology (BWIT) Forum to train around 3,000 rural women to freelance in the ICT sector. In collaboration with Microsoft Foundation, it provided training to 5,000 female UDC entrepreneurs on hardware and software development. Women with very low-incomes participated in self-employment and skill development programs, conducted as part of a project with UNDP. In Chittagong city, 140 women entrepreneurs participated in an innovation camp in November 2016. Among them, nine projects were approved for funding. The a2i program, as part of the fourth pillar of its gender strategy, engages in partnership with development and private organizations in the country to uplift women’s status.

On 5 July 2017, the Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and Information Technology along with the BWIT and Bangladesh Institute of ICT in Development (BIID) held the National Launch of the Women ICT Frontier Initiative (WIFI) in Dhaka City. The event had as its chief guest, Bangladesh Parliament Speaker Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury, and as special guest, Women and Children Affairs Minister Meher Afroze Chumki. WIFI is one of the flagship projects of the United Nations Asian and Pacific Training Center for Information and Communication Technology for Development (UNAPCICT-ESCAP). WIFI aims to promote women’s entrepreneurship through enhancing capabilities of women entrepreneurs in ICT and entrepreneurship so that they and their enterprises can become more productive. So far, there are five modules under WIFI covering business management, ICT skills and ICT-enabled women entrepreneurship, which have been translated into the Bangla language and piloted. The target of the initiative is to empower 25,000 female entrepreneurs in the ESCAP region by 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3_bn2w31Cs

- The above-mentioned figure represents the number of active subscribers only. A subscriber/ connection using the internet during the last ninety (90) days is considered to be an active subscriber.

- The UN counts the aggregate number of Internet users by various platforms - wireless, telephone line, broadband and mobile. The national telecommunications regulator, BRTC, uses a different methodology to measure connectivity – that of counting the number of active Internet subscribers in the past 90 days – and hence, the estimates of the UN and BRTC are different.