5.1 CITIZEN DEMAND FOR SERVICES

According to the most recent Australian Federal Government study on Australians’ use and satisfaction with e-government services, by 2011, two thirds of those surveyed had used e-government channels to contact government.24

More recent survey data from Boston Consulting (2014) places the use of online government services by Australians as currently much higher.25 According to the Boston Consulting survey, Australians use online government services more than citizens in any other country, but satisfaction with those services continues to lag behind that of the United States and the UK. The organization surveyed nearly 13,000 users in twelve countries – including the US, UK, France, The Netherlands, Denmark, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Russia – about their experiences with 37 different online government services in 10 categories.

The survey found 96% of Australians have used online government services in the last two years, with 26% of respondents saying they access online government services at least once a week. The Australian average of 9.2 services used over the past two years was the highest among developed countries. 72% of Australian respondents said they would like to receive more government communications online, while 57% said they would like to use digital channels for voting in parliamentary elections. Other indemand government services include applications and renewals of passports, driver licenses, concession cards, employment services, healthcare and pensions.

When e-government initiatives first came to prominence, the government was in a position to lead by example by educating the public and demonstrating what is possible. The current position in Australia is that demand far outstrips supply. Penetration of smart phones in Australia is the highest in the world. Some commentators are of the view that it is approaching 90%.26 According to Deloitte’s consumer media survey it was already at 81% in 2014.27 Where good services are available, smartphone use extends to government services. By way of example, 65% of South Australians renew their motor vehicle registration online and more than 20% of these transactions are performed via mobile devices.

5.2 ONLINE ACCESS: SEX-DISAGGREGATED DATA

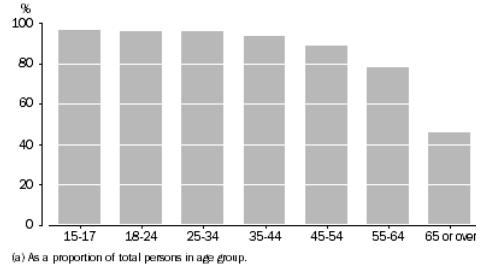

In 2012–13, 83% of people in Australia, were Internet users.28 Compared to other age groups, the 15 to 17 years age group had the highest proportion of Internet users (at 97%). Those 65 years and above comprised the lowest proportion of Internet users (at 46%). See Figure 1 for details.

FIGURE 1

INTERNET USERS BY AGE GROUP (2012-13)29

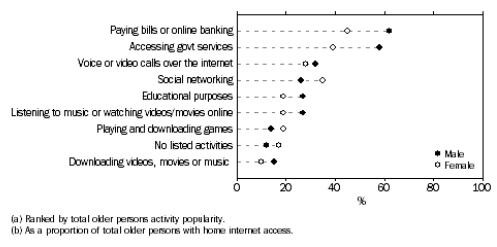

The proportions of men and women accessing the Internet were found to be almost even, at 84% and 83% respectively.30 A further breakdown of data indicates that gender differences become apparent for the age group 65 years and over. In 2012-13, 46% of older persons were Internet users and 44% accessed the Internet from home in the previous 12 months. Despite there being a higher number of females than males in the older persons age group, a greater proportion of male older persons (50%) accessed the Internet at home compared to female older persons (38%). The four most popular types of online activities of older persons were paying bills or banking (55%), accessing government services (50%), social networking and calls over the Internet (both at 30%). Breakdown by sex is shown in Figure 2 below.

FIGURE 2

OLDER PERSONS ONLINE ACTIVITIES AT HOME(A), BY SEX(B), 2012–1331

It is clear that older persons, especially older women, are at greater risk of being unable to access online government services, due to their low levels of familiarity in accessing online information about public services. Members of remote and rural Australian communities constitute another key constituency that run the risk of digital exclusion.32

Connecting SA is an initiative that has attempted to expand people’s access to public information, as highlighted in Box 4 below. This is a critical service, as it follows the steps of other policy frameworks that have foregrounded the importance of access to public information for people’s well being.33

BOX 4

CONNECTING SA

SA Community is South Australia’s (SA) community information directory. Its purpose is to enable citizens to find out about the help available to them from government, non-government and community services throughout SA and find out how citizens can best connect with, and get involved in their community.

Content available through the directory is crowd sourced and moderated by the SA Community team and ultimately its resources are then made available for reuse through open data licensing. SA Community is also integrated with the official South Australian Government website and portal, thereby connecting its users to government resources without it necessarily being under the care and control of the government. In return the portal is able to extend its community outreach with less constraint than is appropriate when publishing from within formal government channels. The Government of South Australia initiated this work and the portal is already well viewed internationally as an exemplar service.

In a paper published by the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS), that organization cited sa.gov.au as an example of best practice. In early 2012 the model was approved by OASIS as the international standard for government transformation.34 This work is relevant to women’s empowerment for a number of reasons including the following:

- Its high use by older women, who are the only Australian female demographic that doesn’t have the same Internet adoption rate as men.

- Its use by persons associated with the community and those supporting NGOs and other volunteer organizations. In fact, women in Australia are both recipients of and strong contributors to the volunteer and NGO sectors.

- Department of Finance and Deregulation-Government of Australia (2011), Australians Use and Satisfaction with government services, http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/interacting-with-government-2011/ , Retrieved 12 November 2015

- Carrasco, M. (2014), Digital Government: Turning the Rhetoric into Reality. The Boston Consulting Group, https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/public_sector_center_consumer_customer_insight_digital_government_turning_rhetoric_into_reality/, Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Rogers Freeman, Emily (2015), Survey: Australian Smartphone and Tablet Usage , Haptic Generation, February 6, http://www.hapticgeneration.com.au/survey-tells-us-how-australians-use-smartphones-and-tablets/

- Deloitte (2014), Media Consumer Survey 2014, Australia media and digital preferences, 3rd edition http://landing.deloitte.com.au/rs/deloitteaus/images/Deloitte_Media_Consumer_Survey_2014.pdf?mkt_tok=3RkMMJWWfF9wsRonuK%2FPd%2B%2FhmjTEU5z16uUpWaGzi4kz2EFye%2BLIHETpodcMTcVnN77YDBceEJhqyQJx-Pr3CKtEN09dxRhLgAA%3D%3D

- ‘Internet users’ refer to people aged 15 years and over, who accessed the Internet from any site within the previous 12 months. Australia Bureau of Statistics (2014), 8146.0 Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2012-13, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/8146.0 Chapter12012-13

- Australia Bureau of Statistics (2014), 8146.0 Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2012-13

- Data from Australia Bureau of Statistics.

- Australia Bureau of Statistics (2014),8146.0 Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2012-13.

- Broadband for the Bush Alliance (2014), Building a better digital future, http://broadbandforthebush.com.au/ wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Broadband-for-the-Bush-Forum-III-COMMUNIQUE-July2014.pdf, Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Clark, J. (2010), Social inclusion in the digital age Housing advice for everyone, Project report. 2010 Shelter

- OASIS, (2012),Transformational Government Framework Primer Version 1.0, http://docs.oasis-open.org/tgf/TGF-Primer/v1.0/TGF-Primer-v1.0.html ,Retrieved 28 July 2015.