1. Introduction: Rationale for Selection

Too often a database is merely viewed as a collection of information that is organised so that it can easily be accessed, managed, and updated. Usually, no gender bias is perceived. However, databases can discriminate, perpetuate gender blind policies and programs, and steer decisions on resource allocation in the following ways:

- what data is collected;

- how data is collected;

- how the data is classified;

- to what extent the data is disaggregated;

- what kind of analyses such a database allows and to what depths or complexity;

- who has 'read' access and to what level of data aggregation;

- who has 'write' access and to what level of privacy and confidentiality; and,

- who has report generation permissions, to what types of reports and what level of detail.

This case study on Malaysia’s eKasih highlights gender-responsive considerations in the design, development, and implementation of a national poverty data bank for poverty alleviation and aid delivery.

2. Background

The eKasih system is a database system that was developed to assist the government of Malaysia to be better able to plan, implement and monitor poverty eradication programs at the national level, and thus, improve the effectiveness of such programs. The National Poverty Data Bank, eKasih was created in October 2007 and was developed in-house by the Implementation Coordination Unit (ICU) under the Prime Minister’s Department (see Figure 1). It was implemented nationwide in July 2008. It won two Asia Pacific ICT Alliance (APICTA) Awards, at both national and international levels, for Best of e-Inclusion & e-Community and Best of e-Government. In 2012, it won the United Nations Public Service Award.

There are six main ministries involved in aid programs/project delivery and distribution. These are the Ministry of Education; the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development; Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry; Ministry of Rural and Regional Development; Ministry of Federal Territories and Urban Wellbeing; and the Ministry of Human Resource. The officially recognised stakeholders of eKasih are the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers of Malaysia, the Chief Secretary to the Government, and the ministries involved in giving assistance. Before eKasih was developed, each of these managed their own poverty aid databases. This resulted, for instance, in duplication of efforts, redundancies, leakages, mismatch in the type of aid given to the recipient, ineffectiveness in measuring impact. eKasih was developed to ensure closer and coordinated inter-agency cooperation so that poverty could be more efficiently and effectively addressed. eKasih was therefore designed for users such as government agencies and officials at state to federal levels.

Figure 1:

The eKasih Web-based System

Source: ekasih.icu.gov.my, 2016.

Initially, enrolment on the eKasih portal was open to all, and citizens could directly register themselves. This practice has since been discontinued and currently, interested applicants are required to contact the Implementation Coordination Unit (ICU), or the State Development Office, or the Federal Development Department (Poverty Eradication Unit) for further information. Applicants are requested to provide information such as their name, telephone contact number or e-mail address, and/or postal address. The validity of the applicant’s poverty status is then verified by the State Development Office against the Department of Statistics' Census of Poor Households and with the help of local leaders (see Figure 2).

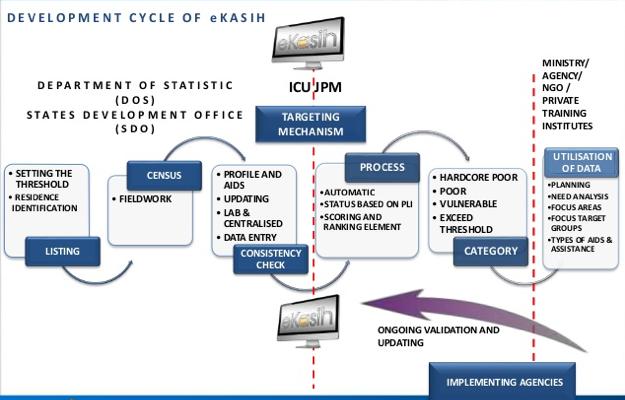

Figure 2:

Development of eKasih

Source: ICU (undated)

eKasih contains the profile of the individual poor and hardcore poor who can be either the head of household or a member of a household. Profile information will include details such as location (parliament, assembly), residence (address, county, state), education, skills and employment, property ownership, health status, and income. Other than the profile information on the individual poor, eKasih as the National Poverty Data Bank also holds records on the type and amount of aid received by the said individual, the agency that provided the aid, the completed application for aid, and monitoring information on the effectiveness of the aid program that was delivered. Updates will include how the individual is benefiting as a result of the aid received in terms of increase in income (if any), and if the individual no longer qualifies for aid (for example, if income has increased above the Poverty Line1 or if the recipient has passed away). eKasih informs the delivery of all aid programs to the poor, including programs such as BR1M (1Malaysia People’s Aid)2 and 1AZAM3.

eKasih also provides for coordination of help information, allows for online updates on poverty information, provides a statistical count of the number of poor and hardcore poor based on the Poverty Line Income per capita, enables the generation of reports and statistics on poverty in the country, and allows for poverty mapping and the monitoring of poverty. The data bank portal has eight modules: registration (pendaftaran), review (semakan), update (kemaskini), reporting (laporan), knowledge base, support, poverty disclosure and the agencies’ list of aid recipients (Senarai Penerima Bantuan or SPB, which includes the list of beneficiaries of ministries and all agencies). Information on eKasih is available on the ICU’s portal, the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development’s portal, and the various websites of State Development Offices.

2.1. eKasih’s Development and System

The development of eKasih was completed in May 2008 (see Figure 2 for the process). At the initial stage of rollout, in June 2008, eKasih was only made accessible to the State Development Office of the ICU. It was then further enhanced and improved based on the feedback gathered from users during this first stage of implementation. As the system was developed in-house, it could easily be modified and enhanced. Finally, eKasih was released to the ministries and agencies both at the federal and state levels in July 2008. eKasih continues to undergo improvements to meet users’ needs and requirements, and to remain aligned to the country’s National Development Policy.

The eKasih system has three main components: a) poverty profile (individual, types of aid, programs/projects), b) Executive Information System (dashboard, GIS, dynamic reporting), and c) Knowledge Base (best practices, e-library). It is an online web-based application system that operates on a proprietary Microsoft platform. The application is running on Windows Server 2003 using Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) 2.0 Web Server. It used Microsoft ASP.NET 2005 as the web development tool and was written using C Sharp (C#). For the content management tools, it used Microsoft SharePoint Server 2007. The web application is connected to Microsoft SQL Server 2005 database engine. A Microsoft consultant is retained to help ensure the smooth implementation of further improvements to the database. The preferred browser for eKasih is Internet Explorer 7.0 and above (IE7.0++).4 This is unlike the ICU’s own portal that allows for optimal browsing on IE7.0++, Firefox, Google, Chrome, and Safari.

The report generated by the application is pre-designed using Microsoft Reporting Services. For the Executive Information System and data analysis, eKasih uses another supporting tool, Speedminer Business Intelligence, to generate an ad-hoc analysis and dynamic reporting for the top management in the form of a dashboard, performance tracking, trajectory, and poverty mapping. ETL Server is used to load the data from the eKasih database to the Business Intelligence Server (EIS module).

Since September 2011, eKasih enhanced its reporting module to a mobile application called ICU Mobile Executive Report (iMEX) which enables the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers, and Chief Secretaries of the related ministries to access eKasih reports through the iPad, iPhone, Blackberry and Androids.

3. Insights on Creating an e-Government Institutional Ecosystem that Promotes Gender Equality.

3.1 Normative Shifts

3.1.1 Closer and Coordinated Inter-Agency Cooperation for Enhanced Efficiency and Effectiveness in Aid Delivery

Prior to eKasih’s development, problems and issues in inter-agency cooperation stemmed from the fact that each ministry or agency involved in poverty eradication programs/projects had their own databases. This meant duplication of efforts, leakages, redundancies, and mismatch of aid to the recipient, resulting in aid delivery systems that were inefficient and not cost effective. Impact studies were also difficult to undertake since these had to rely on piece-meal reports and were often uncoordinated. A user workshop with eKasih’s intended users (the ministries and agencies which were directly involved in the design, delivery, and monitoring of poverty eradication programs and projects) was thus conducted to obtain feedback on their needs and requirements. The design of eKasih was nevertheless primarily top down and supply-driven, with some feedback acquired during a series of road shows in 2008, that were targeted to potential eKasih users at federal and state levels, with the aim of explaining the basic concept of eKasih.

The improvements in eKasih’s inter-agency cooperation was expected to benefit the poor (especially women)5, and improve efficiency and effectiveness in aid delivery.

3.1.2 Gender-inclusive Eligibility Criteria for Aid

Criteria as to who is poor and therefore eligible to apply for aid under eKasih is based on per capita household income as well as aggregate household income. Those who meet the criteria of poverty status based on the 2007 Poverty Line Income (PLI) per capita are eligible for aid under eKasih. Heads of households in urban areas who earn RM1,500 (about USD353) or less a month, or those in rural areas who earn RM1,000 (about USD235) or less a month are encouraged to register on eKasih. Additionally, households with income of less than RM2,300 (about USD541) a month are eligible to register on eKasih.

eKasih allows members of households to apply, and is not restricted only to heads of households. This means that women members of a household who are not heads of households can, on their own, apply for their households to be included in eKasih. Such a measure helps address some power dynamics that can take place within a household, such as neglect of welfare of household members due to the absence of male heads of households.

By using aggregate household income as well as per capita household income to assess poverty, and permitting enrolment of individuals who are not heads of households on the basis of the latter criteria, eKasih recognises that the perceived benefits from household income are not necessarily equally distributed among its members, even if the household approach is used in capturing data on poverty. Women who are not income earners or who suffer domestic violence and other forms of abuse can be denied the benefits of a household income. Globally, research on poverty and women's economic power have shown that when women's income increases, the family tends to benefit directly in terms of having more nutritious food, children's higher school enrollments, and so on compared to when men's income increases.6 These types of studies also show that women-headed households are the poorest not necessarily because they have many children, but because there remains a gender gap in terms of wages paid to women for the same work done by men. Because women in Malaysia generally earn about half of what men earn, this recognition of how poverty is experienced considers the inequalities and discrimination that women can face in seeking their own income, and as household dependents. Many of the beneficiaries of the 1AZAM program, for example, are women. The 1AZAM program is one of the national key result areas identified under the Government Transformation Program. It is designed to aid low-income households out of poverty through their own efforts by engaging in employment (worker placement), agricultural activities, entrepreneurship or the services sector. In 2013, the Government Transformation Program finally expanded its efforts to focus on vulnerable groups like the Orang Asli (indigenous peoples of Peninsular Malaysia), the Penan people (indigenous community in Sarawak), and persons living with HIV. As sub-communities, women tend to be the more vulnerable of these.

3.1.3 Greater Transparency in Aid Delivery

Currently, the portal only allows for login of users who are officials of ministries and agencies involved in poverty eradication programs and does not accept queries without the user logging in. Visitors, however, can make a search of all aid programs implemented in the country and print the information. As of 7 February 2016, there are 3,456 records on agencies and the types of aid they provide. This includes aid that is specifically meant for the Orang Asli (indigenous peoples in Peninsular Malaysia), and women. Clicking on the agency’s name will further provide the name of the aid program, the form of aid (for example, income generating or non-income generating), the code for the aid program, the aid category (e.g. economic, social welfare, education, basic needs), whether the aid provided is under the 1AZAM program, the terms and requirements for applications, the person in charge, and the name of the implementing agency. The record also shows when this information for a specific aid program was recently updated. Visitors to the portal can peruse the news on poverty, the archives (link located at the bottom of the portal’s home page), and the frequently asked questions (FAQ) which outlines eKasih’s objectives, how it is implemented and maintained as the National Poverty Data Bank, and who qualifies for aid.7

3.2 Shifts in Rules/Enforcement

3.2.1 Backbone Connectivity

One of the biggest obstacles in the implementation of eKasih was the lack of network infrastructure readiness, especially in the rural and remote areas where the accessibility and connectivity of the network is unstable and unreliable due to geographical limitations. This meant that government officials in these areas and in the lower tiers of governance were unable to access the data bank. The Government therefore approved the implementation of the National Broadband Initiatives project that focused on upgrading the network infrastructure and bandwidth nationwide. While waiting for the National Broadband Initiatives project to take off, the ICU initiated its own network upgrading exercise in collaboration with the Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU). As a result, network bandwidth for eKasih sites across the nation was upgraded from 64 kbps to a minimum of 256 kbps. The National Broadband Initiatives (NBI) strategy, which was initiated in 2007, is led by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. Since the NBI’s inception, the Commission has set up 4,711 Kampung Tanpa Wayar (wireless villages) and 427 Pusat Internet 1Malaysia (1Malaysia Internet Centres), distributed more than one million netbooks, and implemented High Speed Broadband projects in high economic impact areas as well as widened the broadband coverage around the country to connectivity speeds between 4Mbps and 8Mbps (Unit Perundingan Universiti Malaya and MCMC 2014: xvi).

3.2.2 Local Leaders' Participation in Data Verification

Data and information included in eKasih is based on the Census of Poor Households which is produced by the Department of Statistics. Thus, it uses a household approach in eradicating poverty. Detailed registrations are done by trained enumerators8 for the purpose of verification, and to sign registrants into the eKasih system, who are then certified by the Focus Group, comprising the District Office9 and the ICU at the state level. Local leaders are involved after the initial stage of data capture, highlighting the importance of the involvement of local leaders to verify the accuracy of the data from the Department of Statistics' census-taking on poor households.

3.3 Shifts in Practices

3.3.1 Multiple Sources of Information on the Poor

In addition to the census data captured in eKasih and the involvement of local leaders to verify the information during verification in the field, eKasih also initially allowed for open enrolment by the poor or by those who personally knew them (see Figure 3).10

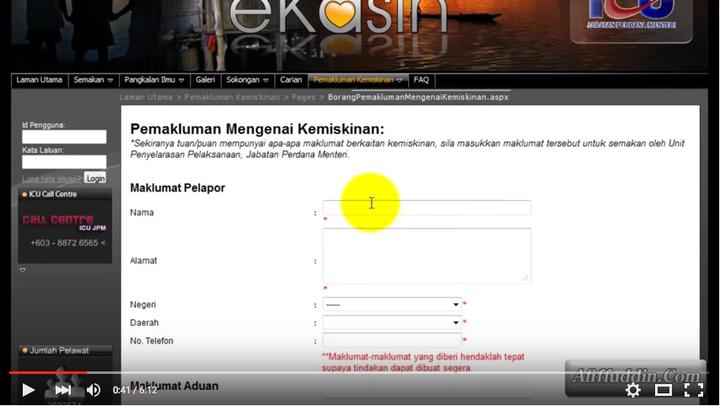

Figure 3:

Open Enrollment on eKasih

Source: Encik Afiff 2014.

Figure 3 above shows the web screen on open enrolment or notification on the poverty form (pemakluman mengenai kemiskinan) that is no longer available on the eKasih portal. The form requests information on the informant (maklumat pelapor) and then information on the concerned poor. eKasih in this way became a source of data and information on the poor in the country that relied on more than one source of knowledge, suggesting an initial attempt to shift from the top-down approach to poverty eradication. When eKasih was first introduced, the decision of who can be considered for aid programs lay not only with government officials but members of the public as well. Nevertheless, verification of the information captured in eKasih was conducted by government officials, and later with the help of local leaders. Households that had been verified in the field and which met the criteria of being poor and hardcore poor in the eKasih database were eligible to be included.11 This initial measure of open enrolment, with a lot of potential for gender-responsiveness, has since been discontinued.

3.3.2 Ease in Confirming Successful Registration for Aid

A new registrant can double-check on her/his registration by just keying in the identification number of her/his MyKad.12 The system will then confirm if the user is registered under the agencies’ list of aid recipients. This is the list of aid recipients whose poverty status is yet to be verified. Information displayed will include the MyKad number, the name of the registrant, whether the individual is the head of household or a member of the household, in which state the resident resides, and the registration status that she or he is an aid recipient.13 Without knowledge of the identification card number, no other person from among the public would be able to check on these details.

4. Impacts on Women's Empowerment

An application of the 'Gender at Work' framework to eKasih reveals that the initiative has produced some empowering outcomes for women at the individual and systemic levels.

Table 1:

Analysis of the Empowerment Outcomes of eKasih Using the Gender at Work Framework

| Informal | Formal | |

|---|---|---|

|

Individual |

Internalised attitudes, values, practices

|

Access to and control over public and private resources

|

|

Systemic |

Socio-cultural norms, beliefs and practices

|

Laws, policies, resource allocations

· Women are better able to check on their aid recipient status. |

At the informal and individual level, eKasih has had an effect on attitudes, values, and practices. Women can feel empowered to self-register on eKasih because of the broad eligibility criteria for registrants that considers intra-household differences in income. Simultaneously, at the informal but systemic level, eKasih has also managed to affect socio-cultural norms, beliefs, and practices. There is an acknowledgment that income earned by individual women members can benefit low-income households that are not women-headed. This is significant since most of the aid recipients are Muslim, as it challenges the belief that men as the heads of households should be the primary contact for such aid programs. The success stories of women beneficiaries under the 1AZAM program, which is served by eKasih, can inspire other women who may be potential aid recipients.

At the formal and individual level, eKasih has affected access to and control over public and private resources. Aid recipients are better targeted and served by the poverty eradication programs that use eKasih. Women are also better able to check their registration status based on their identification card number of their MyKad (MyIdentity), and identify contact persons for the various aid programs. More importantly, through a gender lens, it allows for women to be aid recipients even if they may not be heads of households. This means that women as aid recipients would be better able to have a say over decisions affecting the welfare of their households. In terms of laws, policies, and resource allocations, eKasih as the centralised National Poverty Data Bank allows for greater transparency and accountability in aid distribution. This assists in avoiding leakages and duplication of efforts, and provides for optimisation of resource use.

4.1 eKasih’s Potential

eKasih has potential for addressing impoverishment-related vulnerabilities. However, there needs to be more public outreach to raise awareness of eKasih also among the poor and marginalized populations.14

eKasih also offers important insights on designing integrated databases for poverty alleviation. Every agency responsible for poverty eradication is granted online access to the same source of data according to their scope of responsibilities. eKasih consolidates and centralises the profiling of the nation’s poor. Other than capturing data on income, other types of information are also captured, such as education levels, skills, health status, and property ownership. Agencies are thus able to provide suitable programs for the poor and hardcore poor, based on information stored in eKasih. In addition, they acquire the capacity to forge inter-agency collaboration to design more holistic aid programs that ensure overall wellbeing and sustainability of livelihoods and possibly work towards eradicating risks of impoverishment and perhaps even relative poverty.15 The Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development, for example, monitors specific groups who are high-risk groups for impoverishment through information provided by the Economic Planning Unit (KPWKM 2012).

The poverty status of registrants and poverty mapping of where the poor and hardcore poor are located can be accessed by all registered users. A more effective coordination and monitoring of the impact of aid could thus be possible, and these capacities could be enhanced if open enrolment is reintroduced. Cost issues in verifying registrants as poor or hardcore poor may have accounted for a shift from the self-registration system to a household-based approach based on the Census of Poor Households. Nevertheless, open enrolment would enable a more gender-responsive and inclusive system.

Open enrolment by members of the public would help the government know who has suddenly been impoverished in a timely manner (e.g. individuals who might have been suddenly rendered homeless due to economic downturns etc). Open enrolment recognises that women may migrate for work to different states, and may not be able to directly access the benefits of a household income. By allowing for individuals to register as poor or hardcore poor, the National Poverty Data Bank would be acknowledging that poverty can be experienced at an individual level by women and girls who may be less able to access health, educational, employment, and income generating opportunities compared to male members in the same family.

5. Recommendations

There are three critical areas that could be improved which would further enhance eKasih’s effectiveness and efficiency. The first critical area of concern is the issue of monitoring. Monitoring of poverty status should ideally be over two to three years at minimum to verify if sustainability of livelihoods has been successfully achieved. Most of the success stories under the 1AZAM program for example speak of success after three consecutive months or any three months of achieving a minimum additional income of RM200 over a 12-month period (KPWKM 2014b). While these do speak to successes, in order to identify the sustainability of the success, a longer period of monitoring would be necessary.

The second critical area of concern is in how the disaggregation of data needs to be further improved, such as noted by the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter. In his report on his visit made from 9th to 18th December 2013, the Special Rapporteur noted that, in the case of independent observers, including national civil society organizations and academia, access to information on the situation of specific population groups is limited.16 The disaggregation of data in national household surveys is limited to geographical location (districts and rural and urban populations) and three main population groups (Chinese, Indians and Bumiputra). Such broad categories do not allow for more detailed identification of poor and vulnerable groups in society. Equally, national household surveys do not present statistics disaggregated by sex. The Special Rapporteur had also observed how there is a disregard for the need to disaggregate the data into more meaningful detailed figures. In 2006, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women had also noted the difficulty in finding disaggregated data on poverty rates and the socioeconomic status of women.17

The third critical area of concern is in relation to the design of aid packages. Instead of designing aid packages based on the scope of responsibilities of the involved ministries and agencies, which are often vertically designed based on each sector, aid packages could instead be designed cross-sectorally based on the needs of the poor and those at high risk of impoverishment. By doing so, other target groups under the National Policy on Women could be better accommodated and served by aid programs, such as sex workers, women living with HIV and who face financial difficulties, elderly women who are at risk of impoverishment, women with disabilities, women whose husbands have been imprisoned, women survivors of domestic violence, indigenous women, and women plantation workers (KPWKM undated).

For example, the definition of “single mothers” used by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development does not consider women who are still in the process of seeking a divorce and therefore remain legally married. (Aliah Ali, interview, 2016). According to a spokesperson from Sisters in Islam, in general, Muslim women have had to go through a process of eight years or longer in order to obtain a divorce. This often means, not only do they fall through the cracks of poverty eradication programs that are meant to serve single mothers, but that they also incur large amounts of Syariah legal fees ranging from RM12,000 to RM20,000 in pursuing divorce.18 Muslim women who seek a divorce are unable to rely on legal aid because the lawyers who provide legal aid are already very busy and this would only further delay their cases (Aliah Ali, interview, 2016). As such, Muslim women who seek divorce have to hire and pay Syariah lawyers to take up their cases, which in turn points to the need to set up a legal fund to cover these costs. However, such a legal fund is not listed as a form of aid in the current list of aid programs on eKasih. In this way, the needs of mothers who have been abandoned by their husbands and the remaining target groups under the National Policy on Women and the National Plan of Action for the Advancement of Women require a more holistic approach to poverty eradication and the design and delivery of aid programs.

These target groups will also challenge the current ideas of “productivity” as a criteria to qualify for aid. For example, the main criteria for new applications under the 1AZAM program are that applicants must be 18 to 55 years old, registered in the e-Kasih system, have a monthly income below RM1,500 (urban) or RM1,000 and below (rural) and fall under the category of poor and hardcore poor, and must have a keen interest and the experience of doing small scale businesses (KPWKM 2014a). Other aspects could be considered in addition to job placement, for example aid for career advancement, continuity of women’s education and training could also be deemed aspects of “productivity” (Sumitra Visvanathan, interview, 2016).

eKasih can certainly benefit poor women and become even more effective as an integrated, comprehensive poverty data bank if its purpose is driven by gender-responsive approaches and policies that are designed to address the root causes of gender inequalities in the country. A gender analytical framework should be incorporated and data on income, spending patterns and capacity-building needs should be disaggregated by sex, to better inform policy design, and aid delivery for poverty eradication.

References and Sources of Information

Website of the Implementation Coordination Unit, under the Prime Minister’s Department, Malaysia

Website of the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development

“eKasih”. Accessed 7 February 2016. https://publicadministration.un.org/unpsa/Public_NominationProfile.aspx?id=1406

(undated). eKasih: National data bank of poverty Malaysia. Accessed 7 February 2016. http://www.icu.gov.my/pdf/artikel/ekasih_info.pdf.

Hasan, Zunaidah; Othman, Azhana; Mohd Noor, Abdul Halim; and Mohd Rafien, Nor Shahrina. 2015. “Profiling the poor: Data eKasih Malaysia”. Australian Journal of Business and Economic Studies 1 (2): Accessed 7 February 2016. https://www.aabss.org.au/system/files/published/001002-published-ajbes.pdf.

(undated). eKasih, http://www.slideshare.net/undp-india/malaysia-40048665

Unit Perundingan Universiti Malaya (University of Malaya Consultancy Unit) and MCMC. 2014. Socioeconomic impact study of National Broadband Initiatives Report 2014. Cyberjaya: MCMC.

Encik Afiff. 2014. “Daftar eKasih online: Bagaimana cara mendaftar borang bantuan eKasih”. YouTube video, 6 February. Accessed 7 February 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28dxXSgAZI8.

2014. “Table 6: Gini coefficient by ethnic group, strata and state, Malaysia, 1970–2014”. Accessed 7 February 2016. http://www.epu.gov.my/documents/10124/cb197b81-d86b-418b-b5e9-841f55a68914.

2012. Jejak 1AZAM: Kompilasi buletin 1AZAM dari 2010-2012. Putrajaya: Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat / Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development.

2014a. From zero to hero: Success stories 1AZAM Vol.2 2011–2014. Putrajaya: Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat / Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development.

2014b. Annual Report 2014. Putrajaya: Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat / Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development.

(undated). Dasar Wanita Negara dan Pelan Tindakan Pembangunan Wanita. Kuala Lumpur: Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat / Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development.

Sumitra Visvanathan, Executive Director, Women’s Aid Organisation, interview, 15 February 2016.

Aliah Ali, Communications Officer, Sisters in Islam, interview, 16 February 2016.

- As of November 2011, about 70,000 identified poor and hardcore poor had elevated themselves from poverty.

- A government aid scheme that was established in 2012 for households that earn RM3,000 or about USD706 and below a month in order to combat the rising cost of living. Households that earn between RM3,000 (about USD706) and RM4,000 (about USD941) monthly are still entitled to BR1M but at a lesser amount of RM750 compared to RM950 is paid out in three instalments over 12 months. BR1M aid is also provided to individuals who are not married. These individuals have to be 21 years old and above, and earn RM2,000 a month. Senior citizens aged 60 years and above are also eligible for aid under BR1M. They have to live alone and earn less than RM4,000 (about USD941) a month. Each senior citizen who qualifies for aid under BR1M is entitled to financial assistance of RM650 a year. How senior citizens who live alone and who earn less than RM4,000 are able to qualify for aid, compared to individuals who have to earn RM2,000 and below, is unknown. It is unclear if senior citizens who earn close to RM4,000 would need to show evidence of health issues and/or recurrent medical expenses.

- Under e-Kasih, the government has created a few platforms to facilitate or/and create jobs for citizens through the 1AZAM program. The 1AZAM program can be divided into four sub-programs which are the AZAM Kerja (labour sector), the AZAM Tani (agriculture sector), the AZAM Niaga (business sector), and the AZAM Khidmat (services sector). The Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development is responsible for co-ordinating the 1AZAM programs of e-Kasih that are conducted by the different ministries and government agencies such as the Ministry of Human Resources for AZAM Kerja, the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry for AZAM Tani, the Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia for AZAM Niaga and AZAM Khidmat. Meanwhile, in East Malaysia, the state governments appointed their own agencies. In Sarawak, the agencies responsible for the 1AZAM program are the Department of Agriculture, the Bintulu Development Authority, the Sarawak Bumiputera Development Unit, the Sarawak Timber Industry Development, FAMA, LKIM, GIAT MARA, and the Sarawak Labour Department. In Sabah, the agencies involved are Sabah Usaha Maju Foundation, the Department of Agriculture Sabah, the Sabah Fishermen Cooperation, the Sabah Rural Development Cooperation, the Department of Fisheries Sabah, and the Department of Women Affairs Sabah (Hen Seai Kie 2010; cited in Aziz 2015).

- It is unknown how long this consultant needs to be retained before eKasih can be independently managed and what are the costs.

- An illustration of how eKasih has enabled targeted delivery of services to poor women is the 1AZAM income-generation program aimed at low-income households that uses the eKasih database for targeting, of which over 65% of beneficiaries between January 2011-March 2014 were women.

- See, for example, studies done by the World Bank http://www.bancomundial.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/PLBSummer12latest.pdf.

- The FAQ page, however, is not easy to find on the portal’s home page. One has to make an online search using a search engine before one can get to the specific web page, https://ekasih.icu.gov.my/Pages/FAQ.aspx (last updated 4 June 2013).

- A total of 332 enumerators were trained from among local citizens by the Department of Statistics and deployed nationwide in 2008.

- An eKasih Project Manager is deployed for each district in each of the 14 states across Malaysia for this purpose. The Project Manager is meant to help with the implementation process, conduct user training, resolve any issues that arise, and act as a single point of contact for eKasih.

- This was discontinued in March 2012.

- As at November 2011, there were more than 350,000 heads of household and more than 1.2 million members of households registered and verified in eKasih.

- There is an inadvertent exclusion of those who are poor based on the use of the MyIdentity system for government services as not everyone has a MyKad, such as stateless children and families. Furthermore, discrimination can be further reinforced if the MyKad indicates a permanent resident and hence is not Malaysian, for example, for someone who is a foreign spouse married to a Malaysian.

- Individuals can no longer do online registrations for themselves or for people whom they personally know as poor (or extremely poor) on eKasih. Manual applications, however, are still accepted by the various ministries and agencies that are implementing poverty eradication programs,

- A client of the Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO) could not find information on how exactly she can register on eKasih despite consulting different Ministries and government agencies. She then sought the help of WAO staff. Prior to the woman client approaching WAO for help, WAO had not heard of eKasih or 1AZAM. Eventually, it was found that information on the eKasih portal as in the login screen can be misleading (Sumitra Visvanathan, interview, 2016). The current login screen suggests that people can still register online, but this is not the case. The current login screen only allows those who have already pre-registered and have a login and password to access the database, and its use is largely limited to government officials who are directly involved in poverty eradication programs rather than the beneficiaries. The spokesperson for Sisters in Islam had also not heard of eKasih or 1AZAM prior to the interview with her (Aliah Ali, interview, 2016).

- Income inequality in Malaysia has improved very slowly despite the successes in combatting absolute poverty. In 1970, the index was 0.513, in 1999, it was 0.443 and in 2014, it was 0.401 (EPU 2014).

- See https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/107/52/PDF/G1410752.pdf?OpenElement.

- As per footnote of the Special Rapporteur’s report, CEDAW/C/MYS/CO/2, paras. 15 and 19.

- The amount of Syariah legal fees cited here are based on the experience of Muslim women clients of Sisters in Islam (Aliah Ali, interview, 2016).